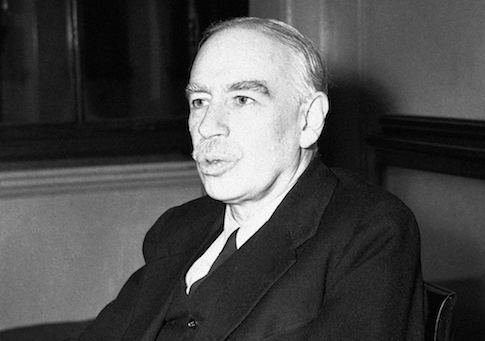

When Carlyle dismissed economics as "the dismal science," he could not have anticipated the glimmering pen of Maynard Keynes, who from the time he began writing at the turn of the last century until his early death in 1946 brought sweetness and light into the gloomy chamber of Ricardo and Marshall, where the general murkiness has not dissipated much since.

Lord Skidelsky’s new anthology of Keynes’s writings, drawn from the 30 volumes of his collected works ably edited by Elizabeth Johnson and Donald Moggridge between 1971 and 1980 as well as his unpublished papers, is the first book of its kind to have appeared. It is long overdue.

It would be a mistake to think that when Keynes was writing to offer advice to the Beveridge Commission or disputing with academic colleagues he was aspiring to the quality of literature. But even in these occasional writings he has a wonderful ear and the ability to produce witty and memorable aphorisms. "When statistics do not make sense," he wrote to his research assistant Erwin Rothbarth in 1940, "I find it generally wiser to prefer sense." "Money is that which one accepts only to get rid of it."

He also had a marvelous talent for verbal abuse. Stanley Baldwin, he told readers of the Times, "has invented the formidable argument that you must not do anything because it will mean that you will not be able to do anything else." "No wonder that man is a Mormon," he wrote of Mariner Eccles, the chairman of the Federal Reserve during the Roosevelt administration. "No single woman could stand him."

For nearly every reader of this book there will be surprises in store. In an unpublished 80-page sketch, he writes approvingly of Burke, who "held, and held rightly, that it can seldom be right to sacrifice the well-being of a nation for a generation, to plunge whole communities in distress, or to destroy a beneficent institution for the sake of a supposed millennium in the comparatively remote future." In passage after passage, he castigates greed, and in "Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren," expresses his hope that one day "love of money … will be recognised for what it is, a somewhat disgusting morbidity, one of those semi-criminal, semi-pathological propensities which one hands over with a shudder to the specialists in mental disease."

Of equal interest are his remarks about the nature of his discipline. In a letter to Roy Harrod on July 16, 1938, Keynes uses the image of Newton’s apple to argue against the view that economics is a natural, as opposed to a "moral," science. "It is as though the fall of the apple to the ground depended on the apple’s motives, on whether it is worthwhile falling to the ground, and whether the ground wanted the apple to fall, and on mistaken calculations on the part of the apple as to how far it was from the centre of the earth." Professional economists—who do not, as a rule, spend much time reading their predecessors—might profit from revisiting the passage in the General Theory in which Keynes condemns a "large portion of recent ‘mathematical’ economics" as "concoctions, as imprecise as the initial assumptions they rest on, which allow the author to lose sight of the complexities and interdependencies of the real world in a maze of pretentious and unhelpful symbols."

But it is outside economics and public policy, in his essays and biographical sketches, where we see Keynes at his best, which is to say, at his most mannered and ebullient. The Economic Consequences of the Peace and Essays in Biography, from the latter of which it would have been nice to see more excerpted here, belong to the same group of slight prose masterpieces as E.M. Forster’s Pharos and Pharillon, the essays of Lytton Strachey, and Logan Pearsall Smith’s Trivia. It is easy to see why, following the advice of Margot Aqsuith, he withheld his fantastical pen portrait of Lloyd George, until after the great man’s death:

How can I convey to the reader, who does not know [Lloyd George], any just impression of this extraordinary figure of our time, this syren, this goat-footed bard, this half-human visitor to our age from the hag-ridden magic and enchanted woods of Celtic antiquity? One catches in his company that flavour of final purposelessness, inner irresponsibility, existence outside or away from our Saxon good and evil, mixed with cunning, remorselessness, love of power?

Nearly as amusing, for those who enjoy this sort of thing, is "Prince" Woodrow Wilson, the fair-haired monarch of the Western Isles who sets out to free "the maid Europe, of eternal youth and beauty," also omitted from Economic Consequences of the Peace:

If only the Prince could cast off the paralysis which creeps on him and, crying to heaven, could make the Sign of the Cross, with a sound of thunder and crashing glass the castle would dissolve, the magicians vanish, and Europe leap to his arms. But in this fairy-tale the forces of the half-world win and the soul of Man is subordinated to the spirits of the earth.

Also of strictly literary interest is "My Early Beliefs," a paper he gave to members of the Bloomsbury Memoir Club in 1938, a beautifully written autobiographical fragment that leaves the reader wishing Keynes had produced a full-length volume of memoirs. This is true despite his occasional eccentricities of judgment—for example, his contention that a single chapter of G.E. Moore’s Principia Ethica, to my mind a windy and tedious book, has "no equal … in literature since Plato"—and his ultimate failure, it seems to me, to defend himself and his contemporaries from the charge of frivolity leveled against them by D.H. Lawrence, the occasion for which the essay was produced.

Not everything here sparkles. Most of the extracts remind us that, its many flashes of wit and humor notwithstanding, the General Theory is a serious book meant for an audience that has studied economics at the post-graduate level. It must be remembered, too, that Keynes was a quintessential Liberal. Everything abhorrent in the Liberalism of his day—the class snobbery that led him to oppose communism in no small part because the proletariat was "boorish"; the unthinking support for the "original genius" of Francis Galton’s eugenics; above all the supreme, unreflective arrogance—is on full view in this anthology.

"In the long run," Keynes famously wrote, "we are all dead." This wonderful book reminds us that his dictum does not apply to literature.