Sir Roger Scruton died in January 2020, before the coronavirus pandemic and its cascading societal effects further weakened the public trust and strained the bonds of our closest affections. We are the worse off.

Scruton had written since the 1970s about reforming the very institutions that make a nation able to withstand crisis. The British philosopher would have brought the same clarity and conviction to the issues that most divide us today. A conservative's "primary concern," he wrote at the end of his life, "is with the aspects of society in which markets have little or no part to play: education, culture, religion, marriage, and the family." And the past two years have shown us cracks in every institutional edifice. School administrators and public health officials are more committed to political action than to their respective disciplines. A majority of Americans are absent from religious services, and an even greater share believe marriage is obsolete. Trust in government and media has reached record lows.

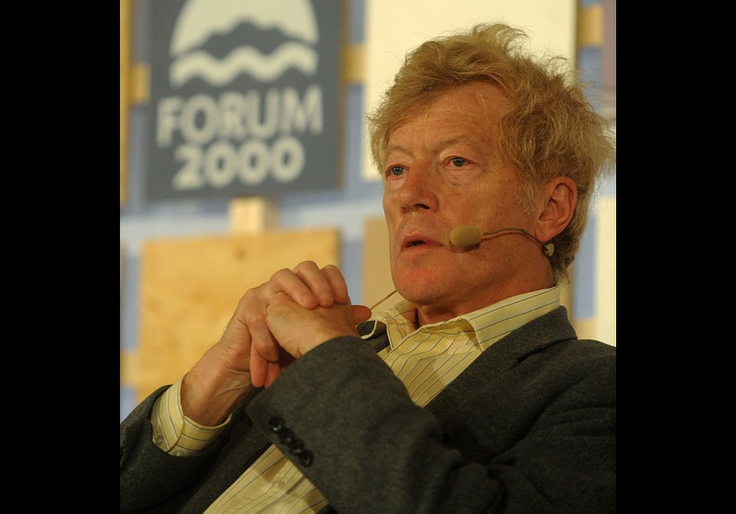

Against the Tide, a new selection of Scruton's journalism, allows us to consider, among other things, how the conservative thinker might have viewed the current state of the West. His literary executor, the Irish philosopher Mark Dooley, has chosen more than 50 of his newspaper columns, grouped by oft-visited themes in the British writer's vast oeuvre. As Dooley notes in the preface, Scruton thought newspaper columns the worst place "to engage in debate" but ideal "to present, as briefly as possible, a distinct point of view." This occasionally lends a stuffy or paternalistic tone to his pronouncements. But on every page, the reader encounters a mind passionately at work, seeking to reconcile everyday problems with a moral sense.

Scruton was not only a philosopher but also a novelist, poet, and composer of operas. Put simply, he was concerned with beauty, and he argued in each of his chosen roles that the modern world had abandoned it. He believed that beauty instructs the moral sense and is our best evidence of the divine. It used to govern our perceptions but has now been replaced by the dictates of science and law. The result is that in the West we live "demystified" lives without a sense of the sacred—from architecture and art to food and sex. Yet the cultivation of the soul through art, religion, and common duty, Scruton wrote, is what can transform even an ordinary modern life into something surprising and profound.

One of the charms of Scruton's prose is that when writing about beauty, it is usually beautiful itself. Consider, for example, his account of first stumbling across a fox hunt in rural England:

One minute I was lost in solitary thoughts, the next I was in a world transfigured by collective energy. Imagine opening your front door one morning to put out the milk bottles and finding yourself in a vast cathedral in ancient Byzantium, the voices of the choir resounding in the dome above you and the congregation gorgeous in their holiday robes. My experience was comparable. The energy that swept me away was neither human nor canine nor equine but a peculiar synthesis of the three: a tribute to centuries of mutual dependence, revived for this moment in ritual form.

This may give the reader the impression that Scruton's preoccupations are little more than private reverie. But his celebration of beauty, order, and the consolations of the Western tradition was rooted in having experienced their absence behind the Iron Curtain. For 10 years before the fall of the Berlin Wall, Scruton traveled to Czechoslovakia with other Western academics to teach dissidents in an underground network of schools. What he saw deeply moved him: "The people I met were quiet, studious, often deeply religious, attempting to build shrines in the catacombs around which small circles of marginalized people could gather to venerate the memory of their national culture." He smuggled books to them and organized lectures but was eventually caught and expelled by the secret police. Teaching in the catacombs taught him, he said, "the transforming effect of sacrifice on the human character."

It also taught him how fragile the social order is. Churches, cultural institutions, and the family—those "natural forms of social life"—will always be vying with the state to maintain their way of life. "Unlike liberalism, with its philosophy of abstract human rights, conservatism is based not in a universal doctrine but in a particular tradition," he writes. Thus, families are the primary custodians of citizens, not the state. Parents are the primary educators of children, not teachers. And "society can be hierarchically ordered without being oppressive." But its success depends upon fulfilling our responsibilities to each other. To ignore them will inevitably place a greater burden on others. In an early essay on education, which points out how much parents have ceded their role as educators to the state, Scruton notes, "Teachers have suffered most of all … from our changed attitude to children."

Careful readers will note how Scruton's love of custom drew him to America. He afforded a dignity to rural Americans that few who live in our major urban centers would extend. In 2004, he purchased and moved to a country estate in Virginia. "For the sheer joy of being alive," he wrote during his time there, "no place compares with rural America: not an Italian fiesta, not an African market, not a Hungarian round dance or a Scottish ceilidh, not even an English fox-hunt, radiates so much love of the earth and its fruits as an American rodeo or point-to-point." He saw in such rustic gatherings the genius of our national spirit.

Scruton did have occasional stylistic faults. His musings, which exhibit a distinctly Romantic temperament, can lapse into grandiosity. He compares in one instance the uncorking of a wine bottle to the sound of "a sacramental bell." In another, telephone booths are referred to as "temples of anxiety." An early essay on feminism in the volume makes its point but sounds rather tinny. To one reader, these excesses come across as whimsical. To another, they may seem pompous.

Reading Against the Tide two years after his death invites the reader to speculate: What might Scruton have had to say about America's summer 2020 riots? And how would he have navigated the tension between civic duty and personal freedom that has been at the heart of our debates over COVID policies?

When I asked his executor, he told me Scruton would likely have favored reasonable COVID restrictions. But he assured me that the conservative writer would have been appalled in 2020 at the ease with which citizens toppled statues and politicians cheered them for doing so. "They would have been on a par with what he saw in France," he told me, referring to Scruton's time in Paris observing the May 1968 student riots. "Yet another and more violent expression of what he called a culture of repudiation or the culture of rejection. And yet another nail in the coffin of Western civilization."

If we wish to conserve America's institutions, we must begin, as Scruton did, by passing on the wisdom of our predecessors. Scruton was an Arcadian, not a Utopian. And to venerate the past, as he did, carries with it a kind of pessimism. "Looking round at the wreck of Ozymandias," he wrote in his diary, "I see how everything is programmed for destruction, and only the thoughts remain." Yet Scruton was also a Christian who believed in resurrection, not merely as a historical event but an eternal one: "It occurs in me and in you, just so long as we put our trust in the possibility of renewal." If we wish to conserve, in other words, we must also begin with hope.

Against the Tide: The best of Roger Scruton's columns, commentaries, and criticism

by Roger Scruton, edited by Mark Dooley

Bloomsbury Continuum, 256 pp., $28