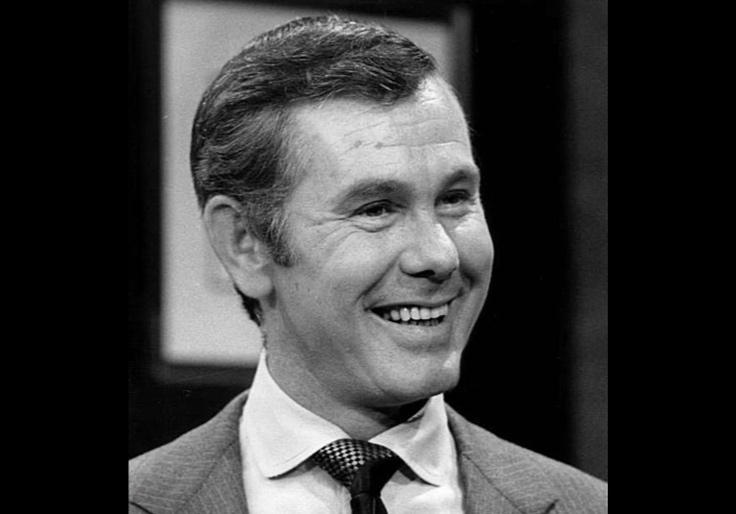

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the birth of Johnny Carson, the late-night television talk show host and, at his peak in the 1970s and '80s, probably the most famous and best-paid entertainer in the USA. To celebrate the occasion we have this just-published fanboy biography, Carson the Magnificent.

The book has had a strange gestation and birth. Just for starters, its author, the magazine writer Bill Zehme, is already dead. When cancer carted him off two years ago, Zehme had been working on the book for more than a dozen years. Chunks of manuscript and half-finished research (book research is never more than half-finished) were picked up by his friend Mike Thomas, also a writer. Thomas added stuff of his own and then jostled the whole thing into a publishable form.

The book thus takes its place in the surprisingly large Carson literature (I don't like the phrase any better than you do). Carson the Magnificent has its distinctions. It seems more reliable than Laurence Leamer's King of the Night. It is less soupy than Stephen Cox's Here's Johnny and more comprehensive than another Here's Johnny! by Carson's TV sidekick Ed McMahon. And it is much less bitter, intimate, and delicious than Johnny Carson, by Henry Bushkin.

Bushkin spent nearly 20 years as Carson's lawyer, business partner, and best friend before falling out with him over a business deal gone bad. His book made a minor scandal when it came out. For anyone who has read it, the Carson of Bushkin's memoir haunts Zehme's far cheerier book like a Dementor. As the ancients knew, no man is hero to his valet or to his personal attorney once he sues him for malpractice and tries to destroy his career. Bushkin's book was published in 2013, nearly a decade after Carson's death, but the whole effort chugs along on the fumes of lingering bile and a deathless resentment. Carson, as Bushkin gives him to us, was a brittle, self-involved, chronically adulterous, dissembling, moody, petty, thin-skinned iceman, capable of wanton acts of personal cruelty.

And he seemed so nice on TV!

Zehme and Thomas are having none of it. Their method of dealing with Bushkin's many revelations and insults is to ignore them altogether. Bushkin's name is scarcely mentioned in Carson the Magnificent. To knowing readers, Zehme's portrait of his subject will seem incomplete as a result, or at best lopsided.

More predictably—and this is my final complaint—the new book is also jumbled in its chronology. Zehme/Thomas have adopted the narrative style of endless Netflix serials, contemporary pulp thrillers, and arty documentaries: Nothing is in sequence, scenes and eras come and go in random order. The book opens with Carson's retirement and we finally get around to the first of his four marriages 200 pages later. Larded in among the shifting scenery—okay, this is my final complaint—is a great deal of clotted rumination.

The thumb-sucking will also be familiar to readers of a certain age. Bill Zehme was a highly regarded celebrity profiler a generation ago, in the twilight era of the slick magazines: Esquire and GQ and Vanity Fair and the other mastodons of a once-mighty industry now decomposing in the tarpits of old media. Their demise is often lamented. Carson the Magnificent raises the question of how much we've really lost.

Maybe not a lot. Here's just a taste of slick-magazine profile prose, comparing Carson with his sidekick McMahon:

Carson, although two years younger, was already three years older in his national profile (if lit by medium wattage at best), whereas McMahon (Massachusetts-bred, solidity personified, ex-Marine colonel/fighter pilot, civilian huckster/shill nonpareil, and workhorse local broadcaster with an insatiable do-anything-and-everything-if-you-please-just-let-him ethos) was strictly a Philadelphia commodity whose barreling ubiquity…

And so on, for another 40 words and at least one more parenthetical aside. In the heyday of the slicks, show biz stardom of any kind could send a celebrity profiler into such flights of rhetorical rapture. But Carson's hold on Zehme was peculiarly intoxicating, and in Carson's prime many reporters shared the fascination. Part of the reason was Carson's own reticence, his unwillingness to be pinned down—rare in a man or woman whose job is to get attention. He seldom granted interviews. It took Zehme 10 years to finally make the score, when Carson was already retired. The star himself complained that his reticence was mistaken for arrogance or aloofness when in fact it was only shyness, a legacy of his Midwestern upbringing.

Carson came from the middle of the country, literally and figuratively. He was born in Iowa and grew up in Nebraska, in a farm town (pop. 10,000) two hours from Omaha. His mother was a homemaker and his father worked various office jobs. Kids were free-range. They rode their bikes to school, took after-school jobs, and hung out at the ice cream parlor. It made for a happy childhood. Carson expressed his affection and gratitude in a TV special called Johnny Goes Home, the only documentary he ever made. It was a version of small-town life idealized and served up by Hollywood and Life magazine and Norman Rockwell. Most Americans understood this version of their country in imagination if not in fact. Yet the reality on which it was based was fading even as Carson rose to embody it in the public mind.

In good middle-American fashion, he considered privacy a virtue. He refused to discuss his political opinions publicly. And he ignored the temptation, then becoming irresistible for celebrities, to make a display of his emotions. (A Carson joke about a Midwestern husband: "He loved his wife so much he almost told her.") At the same time he made a running gag of his own marriage difficulties—the gossip columns made them unavoidable—just as the informal ban in family entertainment on the subject of divorce was coming to an end.

As the years went on, sex figured more obviously in the show's sketches and his interviews with guests, though it never really descended below the level of "naughty," much less to "tasteless." Thirty years after he went off the air, it's clear that Johnny Carson served as a kind of bridge between the conservatism of the 1950s and the cosmopolitan libertinism that by the 1980s had become Hollywood's house style.

His cultural identity also accounts for his astonishing popularity. The fame was comprehensive: It's hard to imagine that any American living through the Carson era didn't know who he was. (He even inspired—and this is saying something—the most insane song ever composed by the Beach Boys' Brian Wilson.) For most of his run, The Tonight Show pulled a 40 share—meaning that 40 percent of the television sets in use at airtime were tuned to Carson. Other networks spent decades trying to dethrone him, throwing up one would-be competitor after another, from the unlikely Pat Sajak to Joan Rivers to Geraldo Rivera. Their failure appeared preordained.

Carson was compensated in sums and perks that would make Croesus blink. By his peak his annual salary ran to $25 million, roughly $85 million today. In return he worked 3 nights a week, 37 weeks out of the year. (A viewer tuning in on a random weeknight would have less than a 50 percent chance of catching a fresh show hosted by Carson; the rest were reruns and guest hosts.) He owned his show outright, along with its mint-like capacity to generate advertising dollars, not to mention the fees NBC paid him to air it. A few weeks of stand-up in Las Vegas could bring in millions more. Even the show's brassy theme song, written by Paul Anka before Carson, exercising droit du seigneur, added his name as co-composer, earned royalties of nearly $2 million a year.

And, this being a Tinsel Town tale, you will not be surprised to learn that none of it made him a happy man. His home life was a mess, even beyond the four wives and the constant philandering. He had three sons he more or less ignored, then felt guilty about ignoring. After the normal bitterness and anger the sons fell to viewing him with an icy detachment. "Work was easy for him, family was not," one of them told Zehme. He took little pleasure in spending his money; his ex-wives and their lawyers took much more pleasure making sure he had less to spend. Abiding friendship eluded him. Bushkin was just one of a decades-long trail of intimate pals who were summarily dropped. The only relationship he managed to maintain was with his vast audience.

That relationship, as Zehme well knew, was an artifact of the time. You can forgive the elegiac tone into which this maddening, enjoyable book sometimes lapses. Carson appealed to, helped create, and feasted on an audience that no longer exists—that did not, in fact, exist for very long at all. It was born of a country bound together by constraints of mass technology: three and only three television networks, homogenous newspapers, a raft of indistinguishable national magazines, a radio dial given over to a handful of genres, musical and otherwise. The shattering of those technological limitations in the digital age shattered the audience. It shattered the country, too, in a way.

After he retired in 1992, Carson nearly vanished from the public eye, making no more than a dozen personal appearances. For 60 years he'd relished his Pall Malls, the most delicious and formidable of unfiltered cigarettes. And so he died of lung cancer five years into the new century, underscoring how thoroughly he belonged to the old. We will not, as the overworked phrase goes, see his like again, for the simple reason that it's no longer possible for any public figure to be so universally loved.

Carson the Magnificent

by Bill Zehme with Mike Thomas

Simon & Schuster, 336 pp., $30

Andrew Ferguson is a contributing writer at the Atlantic and nonresident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.