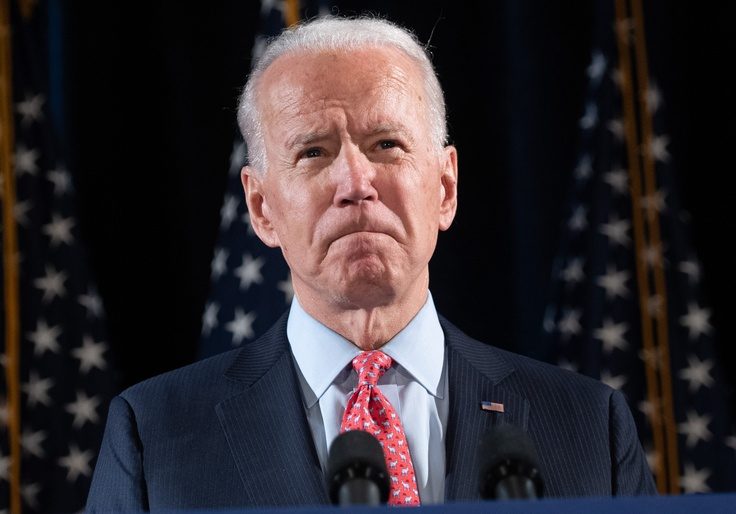

Joe Biden, the presumptive Democratic nominee for president, has pledged to appoint the first African-American woman to the Supreme Court if he prevails in November.

Biden's promise is a nod to the black voters who revived his once-flailing presidential campaign. His zealous courting of black votes has been awkward in stretches, as when he told radio host Charlamagne tha God that African Americans struggling to choose between himself and President Donald Trump "ain't black."

There are two broad groups Biden might select from, the first including sitting judges on federal and state courts, the second with more academic backgrounds. The leftwing group Demand Justice, which is pressing Biden to release a shortlist of potential nominees, has released its own list, which is heavy on academics and cause lawyers. A Washington Free Beacon analysis found the most likely candidates are U.S. District Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson, California Supreme Court Justice Leondra Kruger, and U.S. District Judge Leslie Abrams Gardner, with Stacey Abrams as a possible wildcard pick.

Every president since Ronald Reagan has made at least two appointments to the Supreme Court. Biden's pledge gives him a relatively small pool of candidates with a traditional background for elevation to the High Court. According to biographical data kept by the Federal Judicial Center, there are 17 black female federal judges under the age of 60, the upper limit for Supreme Court nominees in recent decades. Trump's two appointees, Justices Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh, were 49 and 53 respectively. Only a handful of black women on the federal bench are under 55, meaning Biden will have to cast a wider net for potential picks.

If elected, Biden will have to balance three competing problems when selecting a nominee: mounting pressure from the left to pick a candidate with varied occupational experiences, a possible Republican majority in the Senate, and the prospect of an expansive search.

Demand Justice is pressing Biden to pick judicial candidates with civil rights or consumer protection experience, and the group's list includes black professor Michelle Alexander of Union Theological Seminary, best known as the author of a popular, controversial book on incarceration, and NAACP Legal Defense Fund president Sherrilyn Ifill. Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D., Mass.), Biden's onetime rival and a potential vice presidential nominee, has similarly decried "corporate capture of the federal courts"—the concern that judges who worked for corporations or represented them in private practice are too friendly to business.

If Republicans retain control of the Senate, Biden will also have to find a candidate palatable to a caucus that proved unyielding when former president Barack Obama tried to replace the late justice Antonin Scalia. Indeed, the GOP ran a two-year blockade on judicial confirmations in the waning years of the Obama administration, leaving over 100 vacancies for Trump to fill.

Further analyses of the most likely picks in a future Biden administration can be found below.

U.S. District Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson, 49

Jackson, who sits on the federal trial court in Washington, D.C., has already been considered for the Supreme Court. Former president Barack Obama reportedly interviewed Jackson in 2016 for the ill-fated nomination that ultimately went to Judge Merrick Garland. Her stock has only risen in the intervening years.

Since taking the bench in 2013, the judge has decided several high profile matters. Her most significant decision may be a 2019 ruling requiring former White House counsel Don McGahn to comply with a House subpoena, which included pointed rejoinders of President Donald Trump's legal positions. Though her 118-page opinion was much feted among the president's critics, it was overturned on appeal.

Jackson had an unlikely ally in former House speaker Paul Ryan when she was nominated for the federal bench. The judge's husband, Patrick Jackson, is the twin brother of Ryan's brother-in-law William Jackson. Ryan introduced Jackson during her 2012 confirmation hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee.

"Our politics may differ, but my praise for Ketanji's intellect, for her character, for her integrity, it is unequivocal," Ryan told the committee.

Her confirmation would mark the first time that two African Americans have served together on the Supreme Court. Jackson lunched with Justice Clarence Thomas as a Supreme Court clerk and recounted the experience to Kevin Merida and Michael Fletcher for their 2007 book, Supreme Discomfort: The Divided Soul of Clarence Thomas.

"I just sat there the whole time thinking: 'I don't understand you. You sound like my parents. You sound like the people I grew up with,'" Jackson said. "But the lessons he tended to draw from the experiences of the segregated South seemed to be different than those of everybody I know."

Jackson's time in private practice could complicate her prospects. Her résumé—which runs a wide range of law practice—includes experiences liberals will admire, like a three-year tour in the federal public defender's office and a clerkship for Justice Stephen Breyer. Yet she also advised corporate clients for nearly a decade, first for a Washington arbitration boutique, then at such "BigLaw" standbys as Goodwin Procter and Morrison & Foerster.

One leftwing judicial group is already signaling that her tenure in private practice is a problem. Jackson is notably absent from Demand Justice's list of possible nominees.

California Supreme Court Justice Leondra Kruger, 43

Kruger holds the credentials typical of a modern Supreme Court nominee but is free of the professional baggage liberals find problematic.

Following brief stints in private practice and a clerkship for Justice John Paul Stevens, Kruger entered government service as an assistant to the solicitor general, the Justice Department official who represents the U.S. government before the Supreme Court. In that capacity, she argued a dozen cases for the government before the High Court. University of California Hastings College of Law professor Rory Little described her presentation style as polite and "uniformly serious" in a 2015 review of Kruger's Supreme Court arguments.

Her most notable argument came in a 2011 case called Hosanna-Tabor Evangelical Lutheran Church and School v. EEOC, a landmark religious liberty dispute. During oral arguments, the entire bench seemed to think that the Obama administration's position, which Kruger presented, took a dim view of the First Amendment. In his decision for a unanimous Court, Chief Justice John Roberts said the government's position was "remarkable" and "hard to square with the text of the First Amendment itself."

As a justice on the California Supreme Court, Kruger has developed something of a moderate reputation on the left-leaning tribunal. An appeals lawyer who collects data on the California Supreme Court placed her at the "ideological center" of the bench, describing her voting record as "moderately liberal in civil cases, moderately conservative in criminal cases" in a January article. She also dissents sparingly, suggesting a preference for consensus decision-making.

For example, in 2018 Kruger joined with the court's Republican appointees to turn back a challenge to a voter initiative that requires law enforcement to collect DNA samples from people arrested for felonies.

At a general level, her profile tracks Justice Breyer, who sometimes votes with the conservative justices on criminal law issues. A relatively centrist streak could make Kruger's nomination acceptable to Senate Republicans if they hold their majority.

Stacey Abrams, 46

Though Abrams's name is most often mentioned in connection with the vice presidency, her nomination as a justice would address oft-repeated criticisms of the Court's composition.

The justices now serving are something like a legal gentry, ever attentive to decorum and possessed of dazzling credentials. Before becoming judges, all nine served in prestige positions at the Justice Department, practiced at highly selective firms, or taught on leading law faculties. It's an elitist professional bent that skews pro-corporate, pro-government, and pro-prosecution, critics say.

Abrams's workaday legal experience may be an appropriate antidote. After graduating from Yale Law School, Abrams practiced tax law with an Atlanta firm, then advised local officials on public works issues as a deputy city attorney.

Her subsequent tenure as the minority leader in the Georgia General Assembly recalls the early career of retired justice Sandra Day O'Connor, who was the majority leader in the Arizona State Senate in the 1970s. After losing the Georgia governor's race, Abrams founded Fair Fight 2020, a nationwide advocacy and impact litigation group.

As a state legislator turned cause lawyer, Abrams would follow in the tradition of Southern politicians and activists elevated to the High Court by Democratic presidents. The Court's first black member, Justice Thurgood Marshall, was a Marylander who litigated across the South as a lawyer with the NAACP. Likewise, Justice Hugo Black, an Alabaman, was a two-term U.S. senator before his appointment to the Court. A repentant Klansman, Black became a passionate supporter of school desegregation and civil liberties.

Looking beyond the bench could be an asset to the Court. Carl Tobias, a law professor at the University of Richmond who studies judicial selection, told the Free Beacon that the current crop of justices is lacking in both racial and experiential diversity.

"Many observers believe that the Supreme Court needs to be more diverse in multiple ways," he said. "Eight of the nine justices were formerly members of appeals courts and the ninth served as solicitor general."

"On the lower federal courts, there are many more former prosecutors than public defenders and more former big firm and corporate lawyers than lawyers who worked for legal aid," he added.

For her part, Abrams has disclaimed any interest in the High Court for the time being.

"I have no interest in serving as a judge in any capacity at any point," she told the Associated Press on May 7.

U.S. District Judge Leslie Abrams Gardner, 45

Stacey Abrams's younger sister strikes a more familiar figure for a Supreme Court nominee. Abrams Gardner is an Obama appointee on the federal trial court in Macon, Ga., where she has served since 2014.

Former Georgia GOP senators Saxby Chambliss and Johnny Isakson both returned "blue slips" to the Senate Judiciary Committee endorsing her nomination, which came just weeks after the Obama White House and Georgia Republicans struck a deal on judgeships that some Democrats found overly accommodating.

Abrams's personal life is particularly compelling. Her husband, Jimmie Gardner, was falsely imprisoned in a West Virginia penitentiary for 26 years, following wrongful convictions for sexual assault and robbery. Gardner was a victim of the notorious laboratory technician Fred Zain, who fabricated or manipulated evidence in dozens of cases to help state prosecutors obtain convictions. Gardner was released in 2016 and married Abrams two years later.

Before her elevation to the bench, Abrams Gardner practiced in the Washington offices of Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP, where she advised clients like Bank of America and the Radian Group on corruption investigations and complex civil litigation. While at Skadden, she helped prepare an amicus brief for the American Bar Association that urged the Supreme Court to abolish the death penalty for minors. In 2010, she became a federal prosecutor in Atlanta, where she handled a variety of criminal cases and served as a community outreach coordinator. She is a graduate of Yale Law School.

The Biden campaign did not respond to requests for comment for this story.