Paris changes…But in sadness like mine

nothing stirs—new buildings, old

neighborhoods turn to allegory,

and memories weigh more than stone.

From The Swan

Charles Baudelaire, 1857, trans. Richard Howard

Outside of Paris itself, there is perhaps no better place than Washington, D.C., to host an exhibition of Charles Marville’s photographs. A minor pioneer of nineteenth century photography, Marville was responsible for some modest technical innovations. But he is principally and justly remembered for his documentation of the ruthless destruction of Old Paris and its recreation as the City of Light by Baron Haussmann during the second half of the nineteenth century. This civic campaign was conducted under the supervision of Napoleon III, the modernizing dictator of France. After seizing power in a coup in 1852 and legitimizing his regime with a plebiscite, this nephew of the original emperor labored for two decades to improve the lives of his citoyens, whether they liked it or not.

Under Haussman’s plan, the medieval, cramped neighborhoods of Old Paris were replaced with wide, rationally organized boulevards, uniform architecture, and open public spaces. All of this was done in the name of hygienic, economic, and social progress, with an unmistakable subtext of the assertion of the state’s authority. Among the advantages of the new boulevards was that it was much harder to barricade them, a tactic which had grown so regular as to become a hobby for malcontent post-revolutionary Parisians.

Here in Washington, we regularly witness a sort of soft Haussmanization both locally and nationally. Of late, the state has decided to improve our national health care system, in the name—as always—of progress, and has been very successful in razing the flawed system that preceded the reforms, if in little else. As for the local scene, after urban decline bottomed out with the crack-cocaine epidemic of the 1990s, Washington surfed back to civic excellence on great waves of the rest of the country’s money, which has been put to work financing new commercial and residential developments throughout the city. Gentrification may lack the brute tangibility of Haussmann’s percements, but ask the old-line residents of the U Street corridor or Shaw or H Street Northeast what they think about progress, and you might get an earful. If you can find any of those residents; most of them cannot afford the rent.

Gentrification has substantial benefits. A decrease in violent crime, for example, is something that everyone but violent criminals ought to applaud. But the whole process would be a bit more stomachable if one did not have to listen to ambitious young person after ambitious young person announce, in the same breath, that they are deeply committed to social justice and that they have just moved into an awesome three bedroom in Bloomingdale.

The peak of Marville’s career involved the documentation of precisely this phenomenon. Hired by the city authorities in the late 1850s to photograph the Bois de Boulogne, the large park in the western part of the city created by Haussmann, he secured a subsequent contract to photograph streets and buildings that were soon to be destroyed by the campaign of civic renewal. As one wanders through the very fine exhibit put on by the National Gallery, it is impossible to miss that Marville’s new civic subjects were accompanied by a revolution in his own photographic style. His earlier photographs, made after his transition from illustrating to taking pictures, are cramped, conventionally picturesque, and somewhat boring. Rarely are their subjects or their composition of much interest, though a few—The Seine from the Pont du Carrousel and Open Gate—give some hints of the artist’s later approach.

As Marville’s style and technical approach matured --and as photographic technology itself developed-- he rose to the dignity of his mature subject: the transformation of his city. His photographs of the Bois de Boulogne are transitional: the earlier busy look gives way to peace, balance, crisp detail, and, most of all, elegantly framed space. Pictures like The Prefect’s Pond and Stream of Armenonville are characteristic—beautiful, and a departure from what precedes them in the exhibit. They also lay the stylistic foundation for the most important part of the exhibit, and of Marville’s career: the set of photographs known as the Old Paris Album.

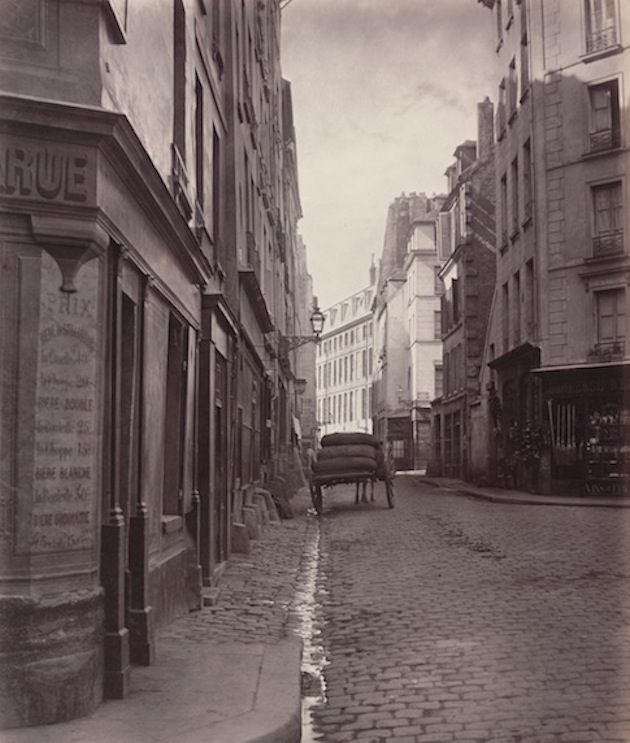

On their own these prints would be worth the National Gallery’s efforts. They are haunting. Due to the long exposure times required for creating a negative, and perhaps also due to artistic preference, these documentary images of a period of great upheaval are largely empty of any evidence of motion; the narrow alleys and arcades are presented to us deserted and still. The few photographs where Marville has posed an assistant or the local inhabitants are all the more striking for being exceptional—the series that captures the workshops along the Bievre River is an example—and one has the sense with these of looking at ghosts. In fact, with these razed neighborhoods, now disappeared beneath Haussmann’s boulevards, that impression really extends to all of the photographs. The streets themselves are ghosts.

With the revival of academic interest in Marville during the 1980s, the photographer stood accused of having been a tool of the Parisian government and of the Second Empire, documenting Old Paris in order to provide justification for its destruction. It is not clear to me that these critics were looking at the same photographs that I am (and the curators of the present exhibit certainly do not share this older critical view). Marville’s pictures of Old Paris seem, to the extent that they have an intrinsic political project, to grant dignity and beauty to neighborhoods that had inarguably grown cramped and filthy. One knows intellectually that the trickle of liquid on the street in pictures like Rue de la Bûcherie cannot be water, but Marville even makes this line of sewage shimmer, guiding the eye towards distant buildings basking in the same light. This is not the work of a photographer out to emphasize the unhygienic filth of the place. Moreover, towards the end of his active years Marville continued to photograph Haussmann’s now nearly complete handiwork. His photographs of the broad boulevards of the new Paris are also deserted, but the character of the pictures is completely different: they are now sterile, full of empty, hazily framed space. During the same time Marville made photographs of the new banlieues on the outskirts of the city to which many of the poor inhabitants of Old Paris had fled. If any of the photographs in this exhibit seem to work to emphasize squalor, it is these.

Paris is famous for inspiring nostalgia. Marville’s photographs of Haussmann’s "street furniture" toward the end of the exhibit, which are the first images that capture recognizably modern Parisian scenes, are sure to inspire such a feeling in anyone who loves or who wants to love the City of Light. It is worth reflecting that these feelings of nostalgia are for an entirely invented place, and that original wave of Parisian nostalgia—the laments of Baudelaire and Balzac and Hugo—was for a city that no longer exists. The destruction and subsequent creation benefitted many, especially the wealthy and the well connected. The refugees in the banlieues did not fare so well.

When the panjandrums of progress come to tell you that they have plans to improve your way of life: look out below.