Around the turn of the fifth century B.C. the followers of Parmenides and Heraclitus got into a rather lively debate about whether the universe was characterized by static being or constant flux—but those guys have been dead for a long time now, and no one much cares anymore what they had to say. The issue has, however, proved to be stubborn. In just the last century, physicists had to confront the puzzling fact that certain tests revealed light itself to be composed of discrete particles, while others showed it to constitute a wave: a controversy as yet unresolved.

A hundred years ago this December, despite the professional inconvenience of the First World War, a Swiss art historian named Heinrich Wölfflin published the third of three major investigations into the development of Western art. In Principles of Art History, Wölfflin proposed to lay the foundations for a "history of art without names," and argued that the transition from 16th to 17th century painting, sculpture, and architecture ought to be understood as a transition in "ways of seeing," from a Renaissance vision of reality as a collection of independent beings, to a Baroque impression of constant flux: an opposition entirely in keeping with the ancient debate.

Wölfflin further proposed, following the bold suggestion of his teacher Jacob Burckhardt, that this transition was merely one example of a periodicity that could be detected throughout the history of art, from the transition between classical to Hellenistic sculpture in ancient Greece, to a similar change from early to late Gothic architecture, to the early moderns themselves, where he chose to focus. Rejecting the notion that one stage ought to be considered somehow better or worse than the other, he wrote "the analogy of budding, blossom, and decay still exerts a misleading influence."

The book proved both widely influential and controversial, was published in two-dozen languages, and has long been available for English readers in a 1932 translation by Marie Hottinger. In honor of its centenary, a new translation has been published, courtesy of Jonathan Blower, to whom much praise is due. He and his editors have given us a decidedly classical Wölfflin, as far as prose is concerned: clear and decisive, not to say compulsively readable for those with even a passing interest in the subject, and this in a field where prose is too often wrecked by jargon and dense academicism.

Of course much of this praise is due to Wölfflin himself, who wrote an elegant book and who, since he was working to establish a revised vocabulary for the analysis of art, was always at pains to clearly define his terms. Wölfflin famously organized his work according to five oppositions that he thought characterized the difference between the Renaissance and the Baroque, the first three of which proceed in correspondence with spatial dimensions: linear vs. painterly; plane vs. recession; closed vs. open form; multiplicity vs. unity; and clearness vs. unclearness.

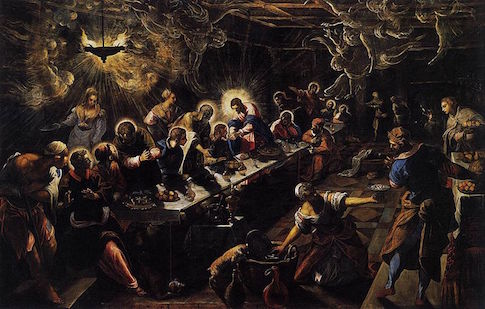

One or two examples indicate what the man was getting at. Leonardo and Tintoretto, to borrow a pairing of which Wölfflin makes heavy use, both treated the subject of Christ’s last supper. In Leonardo’s painting, the disciples are drawn with clear lines, represented on a single plane, in a closed space, are discrete and independent beings, and are seen in an atmosphere of near perfect clarity. For Tintoretto, the opposite of each of these statements is true.

Though both artists are, of course, masters of the illusion wherein three dimensions are represented in two, their ways of envisioning the given subject are totally different: Leonardo’s disciples exist independently, objectively, crisp and permanent in their being. Tintoretto’s world is a moment captured in a universe of change, painterly and subjective. The forms melt into a shared motion; in a sense, the subject of the painting is motion. Wölfflin proposed that motion was the true subject of all Baroque painting, even in genres where such distinctions wouldn’t at first seem to apply, such as formal portraiture, where a brush in the hands of, say, Velázquez, was destined never to produce an image of the Infanta Margarita bounded by discernable lines in clear, enclosed, planar space.

Wölfflin was criticized for the Hegelian determinism of such a theory, and seems to anticipate as much in the book, where he defends himself by saying that just as the grammar and syntax of language condition the relationship of men to the world around them, so the visual language of a period such as the High Renaissance has a similar effect on its artists. And not just painters: sculptors and architects too were subject to the same influences, according to roughly the same patterns. The same cycles could be detected at work within individual souls—the classicism of Titian’s youth giving way to the mannerism of his late period. Indeed, once such a pattern is on your mind, it is hard not to see it everywhere—early and late Turner, for example, or the twentieth century transition from modern to postmodern architecture.

The transition from the Renaissance to the Baroque was not just one instance of more or less equal importance to the rest for Wölfflin, but worthy of special consideration, coming as it did at the beginning of a flourishing of Western representative art that lasted through roughly 1900 (Wölfflin's assessment) and having as its consequence decisive, conditioning effects for everything that followed. Even trends that sought to return to classicism in some way—Dutch realism, for example—were decisively conditioned by what came before them. Vermeer’s calm spaces might at first appear nothing like how most of us would normally picture the Baroque, but just the same could never have been painted in the 16th Century. Vermeer's way of seeing space and color was new, and, Wölfflin argued, had to follow from what preceded it.

Bold on descriptive issues, Wölfflin was more tentative when it came to questions of why such a cycle seemed to appear and re-appear in the arts. He proposed that the movement from classical to Baroque came about as a result of internal forces: a way of seeing contained the next, "just as one finds the germ of the new among wilting foliage." But the return motion, he thought, had more to do with external forces, with a sense of disgust at disorder, a critique that usually manifested itself in ways as much moral as aesthetic: "Diderot attacks Boucher the man, not just the painter." Baroque moments were often prone to exhaustion, of a return to primitivism, just as one sometimes sees in the work of the elderly. "We are familiar with the childishness of old age, the simplicity of fatigue, a rigidity of the painterly without the power of plastic renewal." He had Frank Gehry’s number a hundred years out.

Wölfflin was not the first, of course, to comment on the differences in style among the early moderns, but the clarity of the principles with which he explained those differences, and his thesis that the earlier style led necessarily to its successor according to an internal logic, a logic that likely repeated itself through the ages—this broke ground, and drew criticism from those who felt that Wölfflin was understating the role of external factors, like faith or politics, on artists. In any event, it is interesting to extend his reasoning to other fields, as scholars were quick to do with literature, for example finding something unmistakably Baroque about Shakespeare’s sprawling tragedies, as well as something obviously classical about Racine’s. Though taciturn about any political implications of his research, Wölfflin is quite clear in his conclusion that the pattern he has outlined could provide a means for connecting the history of art to human history more generally. Indeed his book provides powerful documentation for a way of understanding the world that was commonplace for classical and medieval philosophers, but largely forgotten in our more confident age: that human affairs don’t only move in straight lines, but also in cycles.