Documentaries released in actual movie theaters (as opposed to public television or HBO or the streaming services) come in two kinds. First, there's the hysterical, portentous world-is-coming-to-an-end-and-its-all-the-fault-of-the-Koch-brothers-aaaaah-help-call-a-cop kind. Then there's the elegiac-rueful-showbiz-tribute documentary about a once-singular sensation.

I will pass in silence over the first, which is what the first deserves. Also, I am still suffering from PTSD from the time a certain editor at the Weekly Standard once demanded that I review a Michael Moore documentary about health care and I will never forgive you for making me watch it, Fred Barnes. (I was more upset about that than the time Fred blithely drove past me at the entrance to a massive Nicaraguan refugee camp in Honduras in 1986—he got into the camp and I didn't—but that's another story and anyway he is a great reporter and I always stank at it.)

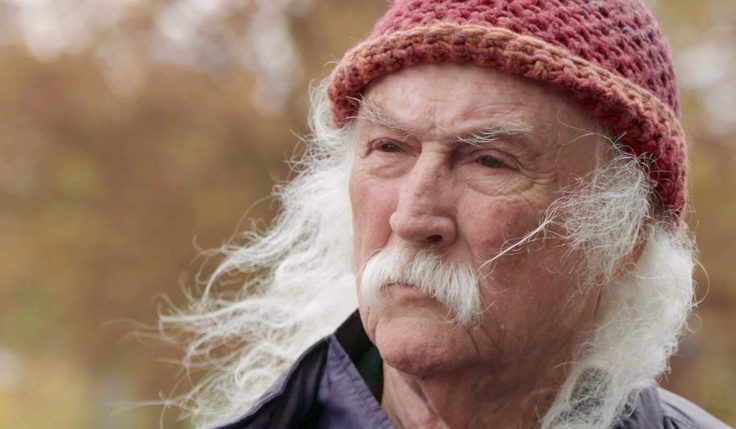

So let’s move on to the elegiac rueful showbiz tribute documentary. There are at least two out and about right now you might want to see, both stewarded by A-list Hollywood talent. One is David Crosby: Remember My Name, in which Cameron Crowe (who made Say Anything and Jerry Maguire) interviews the now-ancient, drug-omnivorous singer-harmonizer. The other is Pavarotti, a biographical portrait of the late operatic tenor whose unlikely director is the heretofore unoperatic Ron Howard. Both pictures are polished, entertaining, diverting, even touching, with fantastic archival footage. The thing is, they're both full of it, in the unique way that only nonfiction works that purport to show the truth but are really only showing the legend can be.

Take David Crosby. The arc of his documentary depends on the idea that he's had this amazing late-in-life surge of creative energy, recording wonderful new solo albums in his mid-70s. The problem is the stuff we hear from the albums is so mediocre and uninteresting it helps explain why he's performing to tiny crowds in out-of-the-way places. Crosby complains he has to keep working because he's the only member of Crosby Stills Nash and Young who never had a solo hit. The movie makes clear why. Also, apparently instead of having had solo hits, what he did for decades was just be a colossal jerk.

He does acknowledge the reason everybody who ever knew him or worked with him hates him like poison has got to be … him. He has a habit (get it, 'cause he was a junkie, a habit, heh) of gratuitous nastiness and self-destructively malign behavior. The fact is, a person with talents as questionable as Crosby’s probably should have conducted himself better and earned more good will with his more gifted associates precisely because they were carrying him to heights he couldn’t have reached himself.

But then it seems we're supposed to think he’s not only redeemed himself with his lousy septuagenarian albums but because he's ended up in a place of honesty. Also, his wife loves him. The story told in David Crosby: Remember My Name is a story about someone whose name doesn't really deserve to be remembered, except perhaps as both a cautionary tale about drug use and a story about how some people make it in showbiz for the strangest of reasons.

Luciano Pavarotti shared avoirdupois problems with David Crosby but little else. He was the possessor of a talent that can only be called God-given. That talent made him one of the most famous people on earth for decades—a man who could sell out solo performances before 100,000 people at will, people who would only see him from a quarter-mile away and through horrendous loudspeakers. But they wanted to say they were there. They wanted to be in proximity to the enormous sound that erupted from his body like lava from Eyjafjallajokull.

Howard's documentary makes this abundantly clear without meaning to do so, because while Pavarotti was a charmer on an epic scale, he was one of the 20th century's foremost performers without having much of a clue that there was a difference in kind, manner, and degree between Mozart and, say, Bono.

Opera straddles a line between overwhelming greatness and all-consuming kitsch, and the true story of Pavarotti's own life is how little he cared about the art and how much he loved the kitsch. Howard does too. The movie dwells on the Three Tenors, the traveling crew he formed with Placido Domingo and Jose Carreras, and it's Howard's conceit that their ludicrous and jokey concerts were the events that made Pavarotti a global superstar. That's nonsense. A decade earlier, Pavarotti was already a worldwide sensation and the most famous classical performer who had ever lived. He was so big that MGM spent an astounding $45 million on a star vehicle for him called Yes, Giorgio—that's $147 million in today's dollars—easily one of the worst movies ever made. It goes unmentioned in Pavarotti, as does his habit of canceling concerts, often at the last minute, and leaving hundreds of thousands if not millions of people in the cold.

Most everything negative about Pavarotti is omitted here, and one strains to understand why. The movie treats his cuddly mask as though it had been his real face, while the real Pavarotti was a far more complex figure—and far more interesting than the human Muppet he's made out to be. In the end, Ron Howard couldn't resist turning Pavarotti into a fictional character in hopes of making him more palatable than he was in real life.

I must go now. I think maybe I'll make a documentary about Fred Barnes.