I grew up with Michael Dirda. Not literally—he grew up in Lorain, Ohio, whereas I’m from the Virginia suburbs of Washington, D.C. He is also 30 years older than I am, though in a coincidence, my father grew up in Lorain, a town that also produced Toni Morrison.

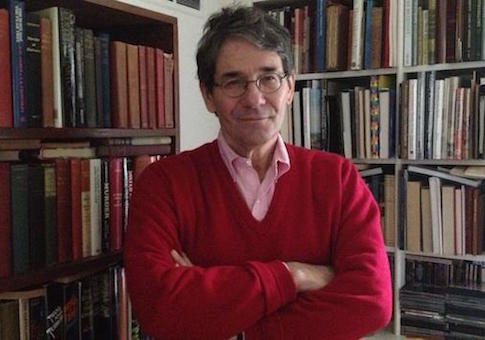

No, I grew up with Dirda in the sense that, entirely unbeknownst to him, I was raised under his tutelage. My parents were Washington Post subscribers, and every Sunday his column in the Post’s Book World molded my adolescent literary taste by providing a humane, rich, and somehow unthreatening introduction to some new book or author or genre—new to me, anyway. Dirda has been writing for the Post for going on 40 years now, and despite the fact that he dislikes calling himself a critic, preferring instead "a bookman, an appreciator, a cheerleader for the old, the neglected, the marginalized, and the forgotten," and occasionally "a literary journalist," he has managed to pick up a Pulitzer Prize for Criticism anyway.

He claims to dislike the term "critic" because feels that he lacks a critic’s "analytic mind," but you could be forgiven for thinking that it’s because a critic is supposed to dislike a book once in a while. Then a critic is supposed to say why he disliked it, in order to maintain the Standards of the Culture, and so forth. Dirda doesn’t do this. What negative things he has to say about an author’s work are always cushioned, while his praise is effusive, though in a careful, well-argued sort of way that persuades you of his honesty. Disarmed, one becomes infected with his sense of delight. This is, of course, a mark of a great teacher.

None of which is to say there aren’t books or authors he doesn’t like—he suggests that there are, from time to time. He just doesn’t write about them, preferring his role as a cheerleader for books that need a boost. Indeed, one of the pleasures of his latest volume, Browsings, a collection of somewhat meandering blog posts originally written for the American Scholar, is realizing that it must have been Dirda who introduced the teenaged me to some book or other—Guy Davenport’s The Geography of the Imagination, say, or Jacques Barzun’s From Dawn to Decadence—that I’ve read and enjoyed having on my shelves for decades now.

Dirda’s mandate from the editors at the American Scholar was to write weekly blog posts that were not reviews of books, but short essays both literary and personal in nature. The project was not, broadly speaking, a success, though reading the posts at the rate of one a week might have provided an experience of brief and pleasant diversion that is harder to achieve when reading them through in order, as Dirda advises one to do in Browsing’s introduction.

The mistake was collecting these musings in the first place. Reading them over the course of a few days, one cannot help but notice tics and flaws that might have been more forgivable in the original format. For example, it is astounding that a man of Dirda’s literary skill and experience has not yet hit upon a graceful way of speaking of his own accomplishments. (Perhaps there is no graceful way to do this.) He won’t be able to get to a beloved book sale on time "because of a talk I’m giving at a conference at—lah-dee-dah—Princeton." A jokey literary society he belonged to was "founded in a bar when four journalists—all winners of a prize that starts with P—were sitting around drinking too much…" Of a minor literary award, "This year’s winner turned out to be—well, aw shucks—me."

Dirda seems to be writing this way intentionally—at one point he refers to his instinct for "self-mockery," and for "ironic deflation as a way of deflecting charges of vanity," but at some point an editor should have been kind enough to point out that he was achieving precisely the opposite effect. Either don’t mention your accomplishments at all, or perhaps better, simply own them. You’re the winner of a prize that starts with P, for God’s sake.

The basic problem is that Dirda on literature, whether highbrow or low, is riveting, but Dirda on Dirda just, well, isn’t. Or, to be more specific, Dirda on Dirda today—on getting stuck in traffic in Northern Virginia, on his anger at Pepco when the power goes out after a storm, on how he should really work on that novel again (this one is mostly in jest, I think), on the need for gun control, on how CEOs earn too much money, on wishing he could himself earn a little more money—isn’t.

Dirda on his past, on the college that he went to and loves, and on the Midwest of his youth is somewhat better, and the only personal essay here that succeeds from start to finish is a lovely, sad reflection on his mother’s advanced age and the melancholy inspired by his memories of the Lorain of his childhood, which he wraps up by quoting the conclusion of Conrad’s Youth.

This seems to be a man who needs some distance from his subject, whose inner life only becomes engaging when it takes the rigorous form of a reflection on some specific thing that he loves, be it an episode from childhood or—in the manner through which he has earned his living—some other person’s book. At one point he "threatens" to start using his blog posts as a forum for writing about obscure books. I shouted at the page, PLEASE DO!

An object of Dirda’s affections that illuminates many of these pages is the purchasing and owning of physical books. I speak from experience when I say that, based on the habits he describes here, it is a miracle the man is solvent, let alone able to pay for multiple children to attend college. (Has he broken bad?) Making the case for his bibliophilia and, in a sense, for his way of life, he writes:

Books don’t just furnish a room. A personal library is a reflection of who you are and who you want to be, of what you value and what you desire, of how much you know and how much more you’d like to know. When I was growing up, there used to be an impressive librarian’s guide entitled Living with Books. I think that’s the right idea. Digital texts are all well and good, but books on shelves are a presence in your life. As such, they become a part of your day-to-day existence, reminding you, chastising you, calling to you.

He is absolutely right, of course, and I have built a library largely along the same principles—and I’m now reminded of where I must have gotten the idea. But I am also struck by how his description of the appeal of those books on the shelves—their reminders, calls, and chastisements, and critically their exciting promise of future knowledge, of the man you might one day become—is similar to the effect Michael Dirda’s reviews had on me as a much younger man. His essays formed an imagined, beckoning library, furnishing the room of my mind long before I had an actual collection of books.

Many of those reviews have since been collected, in Bound to Please, Readings, and a few other places. If there is a young person out there who thinks he would like to have books as a presence in his life: You should buy these volumes right away, and learn, with delight, how much more you’d like to know.