The world is full of amateurs and fools, bumbling their way into dim alleys or falling off the docks into dark water. But maybe the saddest cases are found among the people who actually have some skill: the people who flourish in a profession, productively filling a career, and then decide that their success in one field equips them for success in another.

The problem, I think, is that competent people often think of competence as a general kind of talent, applicable to anything to which they might turn their hand. Unfortunately, competence often proves less fungible and more particular than we like to imagine. To have done one job well doesn’t guarantee an ability to do some other job just as well.

If you ever need an example, you’ll find it in Robert Levinson, the American spy who has been missing in Iran for almost a decade. As recounted by the New York Times reporter Barry Meier in his book Missing Man, Levinson’s tale is by turns shocking, infuriating, and insanely weird—populated with Mafia figures, Russian oligarchs, Columbian drug smugglers, reckless spymasters, and lying diplomats.

But at the same time, Levinson’s story seems almost like a fugue, heading toward its predictable conclusion from the moment the former FBI agent decided to supplement his retirement pension by trying his hand at international intrigue. Once Levinson began contracting part-time with the CIA, he was stumbling toward the end of the dock, where the water is always dark and deep.

As Meier explains in Missing Man, the facts of Levinson’s disappearance are now fairly well known. In 2007, he traveled to Kish, a resort island off the coast of Iran. He did have a letter from British American Tobacco, authorizing him to investigate cigarette smuggling there. But, as it turns out, Levinson himself had forged the letter, and he had actually gone to Iran to gather information he hoped to sell to the Illicit Finance Group of the CIA.

In particular, Levinson seems to have planned a meeting with an American named Teddy Belfield—"a supreme sociopath," according to Meier—who had changed his name to Dawud Salahuddin, assassinated an Iranian dissident in Washington, D.C., and fled to Iran more than 30 years ago. One of Levinson’s old friends, the journalist Ira Silverman, had interviewed Salahuddin, and apparently suggested to Levinson that the man might be growing tired of his Iranian exile. So off Levinson went to see if he could arrange a repatriation, bringing back to the United States all that Salahuddin knew.

It was a crazy plan from the beginning. The idea that the Iranian authorities trusted Salahuddin enough to tell him anything important was ridiculous. And, in any event, Levinson was not the man to flip Salahuddin. A large, beefy American with no Middle Eastern languages and a Jewish-sounding last name, traveling on a letter whose forgery could be revealed with a single phone call, Levinson was marked from the moment he arrived in Iran. He disappeared within hours.

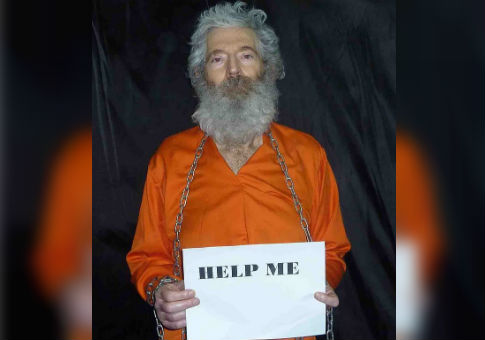

A videotape of him as a prisoner surfaced in 2010. Some photographs followed in 2011 showing him drawn and wasted, dressed in an orange jumpsuit. Iranian officials have always denied knowing anything about his capture, but Meier reports that most analysts think the videos and photos were made by Iranian intelligence officers to spread the idea that some renegade, non-official group had taken Levinson hostage. Regardless, given the five years that have passed since the release of any news (and given Levinson’s history of diabetes and high blood pressure), Meier doubts he is still alive.

This is the point at which Barry Meier’s anger at the United States government kicks in—and rightly so, one has to say. As Missing Man documents, the CIA repeatedly lied about its relation with Levinson. The State Department consistently failed to help find him. The departing Bush administration made little effort on his behalf, and the Obama administration refused to make his release a condition of any of its recent deals with Iran—refused even to put the American’s name on the table for discussion.

Relentless campaigning by Levinson’s wife and seven children eventually brought about congressional investigation, and the CIA was forced to admit that Levinson had done contract work for them. Anne Jablonski, his contact in the Illicit Finance Group, was forced out of the agency with a black mark that left her jobless. But the State Department has essentially taken the position that he was a rogue spy and acknowledging him in any serious way would create more trouble than it would solve.

The reviews of Missing Man over the past few months have generally accepted the Levinson family’s argument that the CIA knowingly sent him to Iran. Meier, however, shies away from that strong claim in the pages of his book—and the former CIA officer Reuel Marc Gerecht, reviewing Missing Man in the Wall Street Journal, points out how unlikely it is that Jablonski or anyone else at the CIA would have approved the former FBI agent’s blundering his way onto Iranian soil.

At the same time, the CIA doesn’t escape blame for the tragedy of Robert Levinson. In the years since his capture, the Obama administration’s feckless cultivation of Iran has turned what might have been a minor embarrassment into a man’s ongoing imprisonment, torture, and probable death. But long before that, the CIA had driven its analysts into a frenzied race for information. The Illicit Finance Group had no business contracting Levinson to venture into international fields where he had no experience or expertise. Jablonski even wrote an email saying that one of her problems was presenting Levinson’s intel to other CIA groups without making them angry. The CIA had developed a culture of internal competition—and then acted shocked when Congress brought to light that one of its groups had tried to out-compete its rivals. The fiasco ended up costing the CIA $2 million, paid in compensation to Levinson’s family.

But the fact remains that Robert Levinson wanted the job. His FBI career had been notable for his work against Mafia crime families, but it ended in quarrels and early retirement—and he needed the money that the international community was offering for information. Perhaps even more, he needed a sense of relevance and importance in his work. When he got a new CIA contract, "he looked buoyant again, like his old self," Meier notes. He felt he was back in the game both financially and professionally.

Robert Levinson had understood who he was, back when he worked for the FBI. He had defined himself as a capable man—a doer of deeds and a getter of things done. Even when his first career was over, he thought of himself as possessing the general talent of competence, ready to be turned to new fields. If the CIA was hungry, and willing to pay good money, for intel from Iran, then a man as capable as a former FBI agent ought to be able to go and get it.

So he pushed to get the contracts, pushed to sell the unlikely tale of a turncoat Dawud Salahuddin knowing vital information, and pushed to make a dangerous trip to Iran. Why is it any surprise that the professionals in a foreign intelligence agency ate him alive? Any spy story that started the way Robert Levinson’s did almost certainly had to end in disaster. Competence is far less commutable than competent people like to think.