As Count John prepared to assume the English throne in April 1199, he traveled to Fontevraud Abbey in the French countryside to witness the burial of his brother and former king, Richard the Lionheart.

Accompanied by Hugh of Lincoln, John observed the ornate sculpture of Christ’s Last Judgment above the door of the abbey. Hugh had an admonition for the soon-to-be-king—avoid the fate of past rulers who, consumed with ambition, lost the favor of the Almighty and were cast into the eternal hellfire:

As Christ sat in majesty, the souls of the departed were being separated into those who would be saved and those who would suffer the eternal anguish of damnation, among them kings in full majestic regalia about to hear the words "Go ye cursed into everlasting fire." John’s response was to draw the sainted bishop to the opposite wall and point to him those kings, made conspicuous by their splendid crowns, who were being conducted joyously by angels to the king of Heaven. "My lord bishop," he said, "you should have shown us these, whom we intend to imitate and whose company we desire to join."

In the view of contemporaries and generations hence, John did not receive the salvation of the latter kings. He died with his kingdom in shambles and a foreign leader in his capital, forever remembered as an ignominious tyrant.

Stephen Church, history professor at the University of East Anglia and author of the new biography King John: And the Road to Magna Carta, writes that this conception is an oversimplification: "John was not a villain capable of the worst venality we can imagine; he was a man placed, by accident of birth, the vagaries of life, and his own ambition, into a position of power for which he proved himself to be ill suited." Above all, it was John’s pride and lack of prudence that most contributed to his misrule. The barons and bishops of his kingdom responded with Magna Carta—a charter of liberties, and a medieval incarnation of the natural rights tradition, that was first issued 800 years ago this month.

Once John (1166-1216) became king in 1199, he faced the threat of a brewing alliance between King Philip Augustus of France and his own nephew, Arthur (interfamilial rivalries were not uncommon). Philip caught John off guard in 1202 by seizing Normandy, then part of the British kingdom, and granting Arthur the rest of John’s lands in France. Arthur even seized the castle where Eleanor of Aquitaine—his grandmother and John’s mother—was staying. John promptly freed his mother, but he squandered his victory. "Puffed up with pride," as one contemporary chronicler put it, he mistreated his prisoners and alienated the French barons who were crucial to his defeat of Arthur. More Normans abandoned him after he executed Arthur in 1203. He returned to England that year, leaving behind ancestral lands in France that he would never reclaim.

Despite his defeats, John planned an opulent Christmas celebration in 1204 where he would wear his full coronation regalia, including a "scarlet dalmatic robe with an edge worked in gold and gemstones." He liked his pomp. And he liked his money. A new tax known as the "Thirteenth"—John’s demand for a thirteenth of all commercial revenues—incensed the local lords who were unable to pass it on to their tenants. John defended the levy as a necessary cost for helping him retake his continental lands in France, but when that effort failed in 1214, the nobles prepared for rebellion.

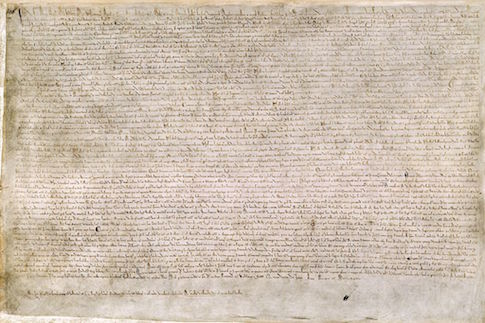

By May of 1215, the rebels had marched into London. The king knew he had to make concessions. At a meadow outside of the capital called Runnymede, John agreed in June to a charter of liberties that would later be known as Magna Carta—Latin for "Great Charter." While several of its provisions dealt with arcane feudal matters and are no longer in effect today, the famous thirty-ninth clause is credited with inspiring modern notions of trial by jury and the rule of law: "No free man will be taken or imprisoned or disseised or outlawed or exiled or in any way ruined, nor shall we go or send against him, save by the lawful judgment of his peers and/or by the law of the land."

The peace achieved by Magna Carta was short-lived. When Pope Innocent III sided with John and declared the charter invalid in August, the barons resumed the civil war. Louis of France, Philip’s son, entered the fray in May 1216 by joining the rebels in London with an invasion force. John died that year from dysentery, likely fearing that his dynasty was at an end. It was his son Henry III—just nine years old at the time—who saved the kingdom with the aid of the veteran knight William Marshal. Marshal finally secured peace with the barons by reissuing Magna Carta in November 1216, and he directed the defeat of Louis’ forces the following year.

Church succeeds in providing a less partisan portrayal of John, demonstrating that it was his hubris and lack of judgment—manifested by the loss of Normandy and the indiscriminate taxing of his subjects—that sealed his fate, rather than a concerted effort to rule despotically. But he falters in discussing the origins of Magna Carta. He breezes through the creation of the charter in a chapter, leaving the reader to wonder why it is still revered eight centuries later.

For biographical works on the period such as Church’s, Magna Carta: The Foundation of Freedom is a requisite companion. Nicholas Vincent, also a history professor at the University of East Anglia, authors most of the essays in this collection while editing the rest. The central theme of the compendium is that Magna Carta represents an attempt to honor older, ancient liberties guaranteed to Englishmen, rights that later found their boldest expression in the American Declaration of Independence. "What King John offered to do in 1215 was not to create a written constitution but to defend and uphold law, liberties and customs already considered ‘just,’ ‘good’ and perhaps above all ‘ancient,’" Vincent writes. "…To this extent, it was not the foundation of English law but an attempt to preserve or restate something regarded as much more ancient and binding."

An early draft version of Magna Carta cites the "Coronation Charter" of Henry I (1100) in its entirety, itself a promise to uphold the law of earlier English kings such as Edward the Confessor (1003-1066). While English rulers frequently broke promises to their followers, they understood that their actions would lack legitimacy without referencing past authority. The 1215 text of Magna Carta repeatedly pledges to sustain the traditional customs and "ancient liberties" of English subjects.

After lying dormant as a document of significance for centuries, Magna Carta enjoyed a recrudescence in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries with the arrival of the printing press and the rise of a remarkable lawyer. Sir Edward Coke (1552-1634), the finest legal mind of his generation, tormented the Stuart kings with his insistence that monarchs derive their authority from English common law and an "ancient constitution"—not God. Magna Carta was a key part of this tradition of ancient liberties. Coke’s battles with Charles I (later executed in the English Civil War) regarding the unlawful imprisonment of subjects resulted in the Petition of Right (1628), an assertion of liberties and property rights that referenced Magna Carta and influenced later thinkers such as John Locke.

America’s Founders certainly studied Coke’s legal writings and his affirmation that any law that violates Magna Carta is invalid. But they challenged his belief in the supremacy of Parliament (Coke was also a member of the body). The Declaration’s pronouncement of "Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness" as unalienable, natural rights was the most profound statement yet about the origins of the ancient liberties observed in Magna Carta. As Silas Downer, a Rhode Island lawyer, put it even before the Declaration in 1768, these natural rights are:

inherent, and cannot be granted by any but the Almighty. It is a natural right which no creature can give, or hath a right to take away. The great charter of liberties, commonly called Magna Carta, doth not give the privileges therein mentioned, nor doth our Charters, but must be considered as only declaratory of our rights, and in affirmance of them.

An otherwise excellent discussion of Magna Carta’s origins and its contribution to the natural rights tradition, Vincent’s compilation errs in its conclusions about the relevance of the great charter today. Richard Goldstone, a former judge on South Africa’s highest court, writes in the collection’s final essay that U.S. detention and surveillance policies in the fight against terrorism have "seriously weakened the application of the rule of law in the United States" and undermined the principles of Magna Carta. Goldstone is of course the leading author of the infamous "Goldstone Report" that accused Israel of intentionally committing war crimes against Gazans in the 2008 conflict, an erroneous charge that he later admitted was false.

Goldstone’s claim that U.S. anti-terror policies violate Magna Carta has been frequently parroted on the Left, most recently by Noam Chomsky. But in doing so, progressives elide the fact that as long as man has declared the existence of natural rights, rogue regimes and non-state actors have arisen to discredit them. From the barbarians at the Roman gates to the present-day jihadists of Iraq and Syria, they have denied that a universal morality is possible and sought to return mankind to its bloody, tribal past. Constitutional regimes like that of the United States have labored to protect and promote these ideals, at times compromising them to defeat adversaries. But if America cannot, or no longer aspires to, protect and promote ancient liberties with extraordinary measures, they will effectively cease to exist.