What do the following have in common?

- The demand on campuses that history, philosophy and literature deemed offensive (including Greek mythology and Shakespeare) must be assigned a "trigger warning" so that students will feel "safe."

- The demand that all traces of the American South be removed from public life, including monuments to Civil War generals.

- The demand that America open its borders to Syrian refugees and to all of the world’s disadvantaged.

These demands are all premised on the assumption that human beings are isolated monads without any connection to history, tradition, or precedent, and can be interchanged with identical monads in all countries and cultures without any serious acclimatization or difficulties. Just as a world of "open borders" can be achieved without difficulty, so can absolute equality of condition among these equal integers, virtually overnight. Any failure to do so immediately, and any record of having failed to do so immediately in the past, must be condemned unconditionally, and all historical traces of it stigmatized and removed. Progressive politics, these people believe, requires a war on history, especially America’s history.

In effect, it is a new kind of tyranny, a psychology of inner totalitarianism spreading through the world’s most democratic society. The great totalitarian revolutions beginning with the Jacobins and continuing through the Bolsheviks, Nazis, and Khmer Rouge attempted to submerge the individual in a utopian collective, achieving total equality virtually overnight through the outward use of terror and genocide. Edmund Burke understood that the French Revolution aimed to create a new kind of human being "devoid of habit, tradition, custom, and variety." Under the revolutionary state, "differences must be sheared off, like canceling equations in algebra." As an eye-witness to the Jacobin Terror, Wordsworth believed it wanted to create an "abstract" human being, "Reason’s naked self," stripped of all customary ties and inherited loyalties, ready to be collectivized with other abstract selves, "Dragging all precepts, judgments, maxims, creeds / Like culprits to the bar."

As outward totalitarianism collapsed in Eastern Europe in 1989 and migrated to the Muslim world in the form of Jihadist groups bent on creating a world-wide Caliphate, the totalitarian dynamic first spotted by Burke and Wordsworth for creating a totally empty individual may, unfortunately, be re-emerging in America as an inward, psychic phenomenon that nevertheless has an agenda for outward radical transformation. While we can spot tyrannical regimes and movements like ISIS out in the open, coming straight for us, this new kind of inner totalitarianism is spreading in our own midst, eating away at civic culture and education by denuding the soul. It does not rely on force and terror, but on indoctrination and the intimidation of those who would dare disagree.

One casualty of the war on history is our loss of an appreciation for political compromise, for "trimmers" who are flexible on tactics so as to advance a long-term principled goal. Lincoln, for example, had to tolerate the Know-Nothings because their Protestant leaders were frequently also the backbone of Abolitionism. In order to pass the Civil Rights Act, Lyndon Johnson had to settle for initially weak enforcement provisions—regulatory teeth were only added over subsequent years.

Of course, the call for gradualism and compromise can be an excuse for racism and plutocracy. But to act as if America has nothing redeemable in its past is to ignore our progress to date and how it was achieved. History instructs us about our best and worst capacities. To walk through a civil war battlefield, for instance, produces a feeling of somber reflection that is a crucial component of learning to be a citizen. The conversion of the grounds of Robert E. Lee’s house in Arlington into a cemetery by a vindictive Union general unexpectedly grew over time into a quiet oasis where the memory of the South’s greatest soldier melds with honoring the fallen dead of every war since. Lee knew that slavery was evil, but he accepted it, and could not place its abolition above his loyalty to his home state. He was wrong, but representative. Removing his statues, as is now being demanded, will simply erase our ability to reflect on the tragically mixed motives of that conflict and learn from them. And if we must erase Lee’s memory, can the slave-holding Founders including Washington and Jefferson be far behind?

We need to restore a fully rounded sense of American character and tradition, warts and all, pros and cons, idealists and realists. Affecting to be "afraid" of that complexity builds not citizens but cream puffs who scream four-letter invectives while whining about an ethnically insensitive Hallowe’en costume.

Just as a deep sense of American character needs to be retrieved, so must long and sober thought be given about whether, to what extent, and how long it will take for newcomers from non-Western cultures, like the Syrian refugees, to absorb the traits of a secular society in which religion is enshrined as a matter of purely private choice and men and women have equal rights. Is assimilation impossible? Not at all, as past history demonstrates. But some cultures may assimilate less easily than others. Muslims in Europe have shown strong resistance to doing so, and a recent WZB Berlin Social Science Center poll found that a majority of Muslims want Sharia law to have precedence over the secular laws of the European states in which they live. The U.K.’s Sharia Councils have been criticized as an alternative legal system that discriminates against women. Caution and even a degree of prudent pessimism are warranted.

Here, too, though, optimists about the assimilation of the Syrian refugees assume that, at bottom, human beings are identical integers who can be stripped of their historical and cultural contexts overnight and plopped down in an entirely different civilization, expected to integrate without difficulty, forgetting that it took some four hundred years in the West for people to be acculturated to the values of individualism and tolerance (and we’re not there yet). This anti-historical view of human behavior, which overlooks the deeply ingrained differences between systems of government and political traditions is confined neither to the Left nor the Right, as evidenced by conservatives who endorsed President Obama’s expedited program for Syrian refugee admission on the grounds that "America is an idea," implying that everyone in the world is by nature a Jeffersonian individualist who need only be offered the chance to flourish in the land of individualism. Edmund Burke might respond: "America isn’t only an idea. Americans are a people, with their own historical path-way."

In the conclusion of my recent book Tyrants: A History of Power, Injustice, and Terror, I sketch a "homeopathic cure" for the temptation of tyranny through the study of the Great Books, starting with Plato’s Republic. In other words, to see tyranny when it’s headed for you, you have to have some inkling of what it is and the psychology behind it. That’s true of the threat posed by older-fashioned totalitarian movements like ISIS, and it’s also true of our new inward totalitarianism.

But I’m becoming more and more convinced that not only do we need the Great Books, but we just as much need what I call the Next Best Books — great histories, biographies, novels, and the memoirs of statesmen. I have always believed that the Great Books help us to understand history, including its distaff side. More and more, though, I have come to believe that a knowledge of history is also needed to help people understand the Great Books, especially today’s young people, who through no fault of their own are educated to become historical blanks and ciphers. If you have no inkling of the danger posed by tyranny throughout history, how will you be able to fathom why it is so important a theme in, say, Plato’s Republic? And how will you spot it in the world around us, and in our own midst? Ben Rhodes’ sneering remarks about the historical ignorance of today’s reporters, and how it helped him pull the wool over the public’s eyes with respect to Iran, were an accurate assessment of what today’s education system produces.

To resist the war on history and its barren understanding of the American character, we need to re-envision the university curriculum. Such a re-envisioning needs to be initiated largely from outside the academy (though the effort should include academics), for nothing less than an alternative curriculum for a historical education in political life is needed to counter-act the universities’ neglect. Once constructed, there’s a fair chance that this alternative curriculum might begin to edge its way back into the academy itself. Lots of professors and students would be cheering it on.

One place to start would be for students to read what the American Founders read in college, traditional political historians like Polybius, Cicero, and Sallust. At a minimum, students should read the great classics of Cold War history (it might cure them of what they think is appealing about socialism). And let us surely not forget the canonical literary figures who brilliantly illustrate the perennial dilemmas of war, peace, and statesmanship, including Shakespeare, Tolstoy, Flaubert, and Turgenev. The same goes for a grounding in comparative religion and in music.

But history is the key. So to get the ball rolling, here is one man’s Top 15 List of the Next Best Books, what every student should read at a minimum to become a historically literate citizen. I’m excluding topical commentary about education, culture and politics, brilliant though it may be (like Bloom or Paglia), and focusing on historical narratives of the great milestones of the West, written for a general readership. In order to stave off the flying cudgels of my fellow scholars, I have stuck (with one exception) to writers no longer living. There are scads of other candidates, so debate about the adequacy of my list is both inevitable and welcome.

- H.D.F. Kitto, The Greeks. An overview of the civilization that formed the West.

- Ronald Syme, The Roman Revolution. How the Roman Republic became a world monarchy in disguise.

- Edward Gibbon, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. An Enlightenment historian surveys the career of the greatest state yet known to mankind.

- Lord Bryce, The Holy Roman Empire. The emergence of medieval Europe on the ruins of the Roman empire and the centuries-long struggle between Church and State.

- R. H. Tawney, Religion and the Rise of Capitalism. How the modern age was born of a unique synthesis of Renaissance and Reformation individualism.

- Louis Hartz, The Liberal Tradition in America. Why America’s only deep tradition is individualism.

- Lord Charnwood, Abraham Lincoln. A masterful political and psychological portrait of America’s greatest president.

- Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation. Advocated Europe’s retreat from laissez-faire individualism and the restoration of an organic view of society, mirrored in Social Democracy and paternalist Conservatism.

- Barbara Tuchman, The Guns of August. A grab-you-by-the-lapels account of how Europe, at the apex of its culture and prosperity, plunged into the horrors of World War One.

- Jose Ortega y Gassett, The Revolt of the Masses. Fascism as the lust of the masses to smash the high civilizational standards of 19th century Europe.

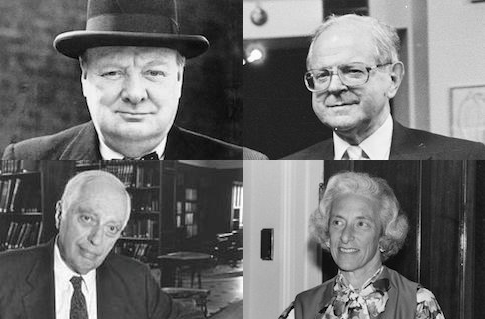

- Winston Churchill, Great Contemporaries. Matchless short portraits of the most impressive figures of the era, including pre-war Hitler.

- Robert Conquest, The Harvest of Sorrow. Indispensable for revealing the crime of Soviet genocide, on a par with the Holocaust.

- Lucy Dawidowicz, The War Against the Jews. Among the first to establish that the Holocaust was Hitler’s central and over-riding policy guiding World War II.

- Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago. The conclusion to Volume Two "The Soul and Barbed Wire" says it all.

- Bernard Lewis, The Crisis of Islam. How a great civilization declined into a seedbed for Jihadist fundamentalism.

My call for renewed attention to the Next Best Books takes nothing away from the centrality of the Great Books to a liberal education. To a considerable extent, the Greats can take care of themselves. Looking at the university from the outside, it’s easy to conclude that traditional liberal education is doomed as what Roger Kimball calls "the cry-bullies" demand that the canon be "decolonized." But while that needs to be resisted, a lot of teaching and learning of the canon still goes on unimpeded. A recent study of the ten books most frequently taught at leading universities was comparatively reassuring—Homer, Plato, Aristotle, Machiavelli, Kant, and Tocqueville are still at the top of the charts.

Our more urgent task is to fill the gap between the starry firmament of the Greats and the souls of our young people before they are entirely drained of any knowledge of the past—of the subtleties and complexities of human psychology and man’s capacity for noble and base behavior—turning them into something like the empty integers that the new totalitarianism wants them to be. And that historical depth will, as I’ve said, give them a keener insight into the core texts themselves, a bridge from the here and now to the stars. Let’s get started.