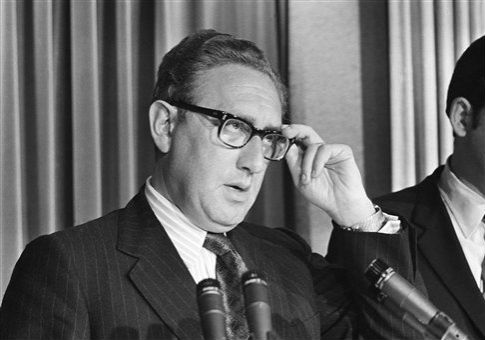

In the first part of a projected two-volume biography, Niall Ferguson challenges us to re-consider Henry Kissinger’s formative years. A Harvard professor, historian, and media personality, Ferguson is serving as Kissinger’s authorized biographer. Pushing back against the notion of Kissinger as a Machiavellian ultra-realist, Ferguson synthesizes tens of thousands of documents into 878 pages of narrative, supported by thousands of notes.

Kissinger was raised in Furth, Bavaria, near the center of Nazism’s rise to power. Ferguson relates how the first victims of fascist prejudice were Jewish doctors serving Furth’s population. Next was the familiar propaganda, the boycotts of Jewish stores, then the beatings and the social segregation of Jews in Furth’s schools and institutions. Ferguson’s detailed account here is instrumental to our understanding of Kissinger’s early years. These formative experiences shaped Kissinger’s hatred of authoritarianism.

Fortunately in 1938, the Kissingers were able to escape to New York City. Many in his extended family were less lucky. While much easier than life in Furth, the immigrant Kissinger’s time in American high school was far from easy. Struggling with the intricacies of stateside dating and embarrassed by his sharp German accent, Kissinger chose to stay quiet and write long letters. He also suffered at the hands of Irish gangs targeting new immigrants.

After excelling in his academic studies, at the outset of America’s involvement in the Second World War, Kissinger was sent by the Army to college to learn critical skills. The purpose of this program was to enrich intellectually gifted young officers. However, in an fine example bureaucratic ineptitude, Kissinger was sent to a conventional unit before completing his studies. Soon thereafter, he was deployed to Europe with an infantry unit.

Kissinger participated in tough combat on the push towards and into Germany. Ferguson notes that Kissinger displayed three key traits in his wartime service that stuck with him throughout his life. First, he was impatient and seized the imitative. Second, he was willing to take risks. Third, he was able to conceal his fear with humor. After the war’s conclusion he was decorated with the Bronze Star for helping to lead a successful program to capture Nazi fugitives.

Kissinger took up residence in Boston to continue his academic pursuits, eventually joining the faculty of Harvard. We see that in these early years Kissinger struggled to earn a living and to balance public advocacy with academic duties. Only time and the beneficence of donors gave Kissinger his rise in visibility. Reviewing Kissinger’s early writings and disputes, Ferguson re-publicizes the extraordinary range of work Kissinger produced. Kissinger warned that the Soviets would seek "the neutralization of the United States, at much less risk by gradually eroding the peripheral areas, which will imperceptibly shift the balance of power against us [the US] without ever presenting a clear cut challenge." This was remarkably prescient for its time, early in the Cold War, and remains applicable to Putin’s Russia today.

Ferguson throughout is a pains to demonstrate that the caricature of Kissinger as an arch-realist is just that, a caricature, it is possible to see the seeds of such an interpretation in his writings. Consider this passage, cited by Ferguson, from Nuclear Weapons and Foreign Policy:

While we should never give up our principles, we must also realize that we cannot maintain our principles unless we survive … It would be comforting if we could confine our actions to situations in which our moral, legal and military positions are completely in harmony and where legitimacy is most in accord with the requirements of survival.

As Ferguson argues, this appreciation of what it means to be between a rock and a hard place puts the nature of Kissinger’s idealism in the neighborhood of Kant: "it was an inherently moral act to make a choice between lesser and greater evils." In Kissinger’s early but influential advisory roles, Ferguson finds the best evidence for his thesis. Contrasting Kissinger’s willingness to challenge the Soviet Union militarily during the 1961 Berlin Crisis with Kennedy’s pragmatism, Ferguson notes that "we may thank our lucky stars that pragmatism rather than [Kissinger’s] idealism prevailed in the situation room."

For those with an interest in Kissinger or the history of American foreign policy, Ferguson’s original argument, immense research, and accessible prose make this a deeply compelling read.