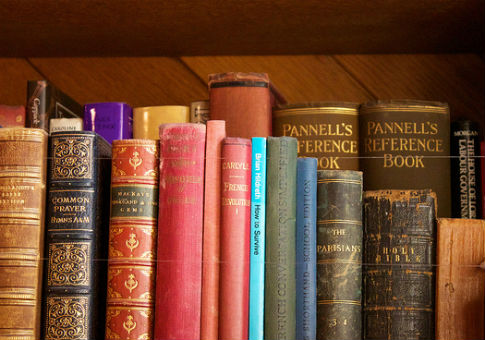

My wife and I have a Larousse Gastronomique on the bookshelf in the dining room. A Classical encyclopedia and Hoyle’s Rules of Games in the parlor. Dictionaries for translating Latin, Greek, French, German, and Spanish kicking around somewhere. A set of atlases, the old two-volume microprint of the Oxford English Dictionary, and a battered, spine-cracked copy of Roget’s Thesaurus—together with Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations, Granger’s Index to Poetry, and Strong’s Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible. Nick De Firmian’s index of modern chess openings, of course. Grove’s Dictionary of Music and Musicians. The Chicago Manual of Style. The Cambridge History of English Literature. Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable. The Baseball Encyclopedia.

In his new book, You Could Look It Up, Jack Lynch chronicles the history of such reference books, and reading his entertaining account made me realize just how much of the stuff we have on shelves all through the house. Unfortunately, Lynch also made me realize how rarely any of it gets pulled down for a look these days. The reference book is dead—killed off by the Internet and the physical ease that tablets and cellphones now allow.

You want to know the origin of the phrase "hell-bent for leather"? The attributes of Melinoë, Persephone’s ghost-guiding daughter? Maybe the melting point of silver is what you need (it’s 1,763 degrees Fahrenheit). The shortstop for the 1931 A’s (Dib Williams). The electoral votes Barry Goldwater managed in 1964 (52). Most Oscars in a career (Walt Disney, with 22). The date of Wilt Chamberlain’s 100-point game (March 2, 1962).

Much of that information is here, somewhere in the house, and the rest findable in any reasonable public library. But why would we bother? I didn’t bother just now, while digging up these stray tidbits of fact. For that matter, why would we plow through the 80-odd cookbooks in the pantry, seeking something as mundane as the government’s recommended internal temperature for a pork roast? (145 degrees, the Internet reports.) In a fit of bad timing, an expensive failure to predict the course of culture, my wife and I spent decades building a good, general-purpose collection of reference books—and we finished the work right at the moment when general-purpose reference books ceased to matter. Ceased to be consulted. Ceased (as with such once-dominant publications as the Encyclopædia Britannica and the Readers’ Guide to Periodical Literature) to be printed at all.

That’s not quite the story Jack Lynch wants to tell in You Could Look It Up. An English professor at Rutgers and author of The Lexicographer’s Dilemma—a 2009 account of the debates, from Shakespeare’s time to our own, about what constitutes "proper" English—Lynch wants to celebrate reference books as the foundation of, well, everything. These volumes give us social cohesion. They’re the root of literary, scientific, and even political culture. There’s nothing that reference books can’t do, for Jack Lynch. Nothing that they haven’t done, for that matter, and he lays out the history of reference to demonstrate just how much the march of history depends on the "concentrated wisdom" of reliable reference books.

Curiously, Lynch refuses the form of a reference book in the construction of You Could Look It Up. Instead, he tells the story of 50 reference books by pairing them off in 25 chapters, with each chapter followed by what he calls a half-chapter, rambling around in some other field of reference. Thus, for example, Chapter 20 compares and contrasts Gray’s Anatomy of 1858 with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, first published in 1952—and follows on, in Chapter 20½, with a four-page discussion of abandoned and unfinished reference projects, with no discernible association to his full-chapter tale of medical texts.

The result is more interesting than effective, especially if you’re looking for a systematic history of reference. But Lynch was clearly incapable of writing a reference book about reference books—he wouldn’t know the word systematic if you hit him upside the head with Webster’s Third—so he decided just to have fun in You Could Look It Up. He even includes a wryly self-pitying half-chapter on the odd ways that authors and editors have tried to organize their reference books.

And if you’ve given up on system, why not pair George Grove’s Dictionary of Music and Musicians with Emily Post’s Etiquette in Society? Or the Normans’ eleventh-century census of England in the Domesday Book with Ptolemy’s second-century Geography? By those fun but incomprehensible measures, Lynch is almost coherent in the chapter joining Diderot’s Encyclopédie and the Encyclopædia Britannica, and quite sensible in the chapter contrasting the eccentric character of Samuel Johnson’s go-it-alone English dictionary with the Gallic systematic rationality of group-written work from the Académie Française.

You Could Look It Up doesn’t limit itself to dictionaries or encyclopedias, the fundamentals of reference. Lynch feels free to wander through the tables of logarithms that mathematical and engineering publishers once distributed—and then turn to the Code of Hammurabi. He’ll mention a Japanese language guide for Dutch seamen—and follow it up with sex manuals, from the Kama Sutra to the apocryphal Aristotle’s Masterpiece and on to a rating of London’s prostitutes in the 1761 Harris’s List of Covent Garden Ladies.

Along the way, Lynch hints at his just-below-the-surface thesis of the importance of reference works. Yes, he admits, culture advances with the discovery of new information and new techniques. But it advances more—and, of vital importance, preserves its advances—only when the new information and techniques are organized into reference books. You might have been taught in school that something like Immanuel Kant’s 1784 essay "What Is Enlightenment?" stands as the defining text of the turn to modernity, but for Lynch the right place to look is Diderot’s 1751 Encyclopédie as the real foundation, with its subtitle "A Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts."

That proves a problem for the book when Lynch reaches the Internet revolution. He wants to praise Wikipedia and join in the fun of it all. If there are problems with Wikipedia’s text, so be it: He notes that most reference books in history have hidden beneath their pose of objectivity a set of political and social agendas (often culture-preserving conservatism, like a systematic catechism). Why should online information be any different?

Part of the answer is the removal of even the claim of objective standards and the concision required by the expense of print. Nobody has to decide what is important and what is not, so the Wikipedia article on an early-20th-century American lecturer named Mary Hanford Ford runs around 30,000 words, while the main articles on Diderot and Kant run about 5,000. (Remind me again, what is Enlightenment?)

But Lynch knows that, for good and for ill, the scattershot of online answers will prove—has already proved—the future of reference. The more neutral the fact, the more plausible the historical setting, the more likely the online answer is to be right, since no one has much motive to lie or make a mistake about the melting point of silver, the A’s shortstop in 1931, or the Oscars won by Walt Disney. In the subtitle to You Could Look It Up, Lynch refers to the "reference shelf," rather than the "reference book." That’s a bit of a dodge, a wiggle around the problem of what to call something like Wikipedia, but you know why he does it. You Could Look It Up wants to be a history of reference, but it proves to be reference books’ obituary.