"The restoration of Hebrew," writes Lewis Glinert, professor of Hebrew studies at Dartmouth College, "was an act without precedent in linguistic and sociopolitical history." And as his valuable new book, The Story of Hebrew, demonstrates, it was a conscious decision by Jews who decided that if they were going to make it out of the Diaspora, their language was going to make it, too. So successful were the "guardians of Hebrew's textual memory," that when the time came to restore Hebrew as a spoken tongue after two millennia, they did so, in Glinert's words, "almost overnight."

The importance Jews accorded to Hebrew explains the great lengths they went to preserve it. The principal method was the study of Hebrew texts. Glinert writes that "The day when Bible study became pivotal to Jewish life" was the day Ezra the Scribe read from the Bible in a Jerusalem square, as described in the book of Nehemiah. Ezra had led a group of Jews back from Babylonia around 458 B.C., over a hundred years after the Babylonians had destroyed the First Temple and exiled most of the country's inhabitants. "[I]t's hard to imagine what would have become of the Bible without Ezra," Glinert says. Nehemiah was equally committed, judging from his fury at coming across non-Hebrew speaking Judeans in the city of Ashdod: "And I contended with them and cursed them and beat some of them and pulled out their hair."

Far more threatening to Hebrew would be the destruction of the Second Temple by the Romans. In 135 A.D., Rome smashed the Bar Kochba revolt, the final Jewish rebellion against its rule. One million Jews were sold as slaves, with a remnant fleeing Judea. Exactly how many Hebrew speakers remained is unknown, and was perhaps in the tens of thousands. "By any sociolinguistic yardstick, the prospects of native Hebrew's survival were now minimal," Glinert says.

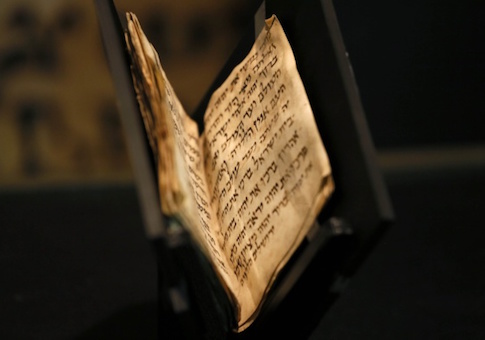

Yet, Hebrew did survive. The Sages, led by Rabbi Judah Ha-Nasi, were the first group of Hebrew guardians that rose after the destruction of the Second Temple. Fearing another calamity, they decided to write down the Oral Law, which became the Mishnah, teachings not found in the Five Books of Moses. According to Glinert, "It is likely that they engaged in a shrewd linguistic calculus. If these texts were set down in Hebrew and duly imbibed, pondered, and memorized, the language could and would survive." Hebrew would be "kept, as it were, refrigerated … It was an extraordinary act of linguistic faith, and it would bear lasting fruit."

Other groups emerged to preserve Hebrew as the centuries wore on. The fourth and fifth centuries saw the paytanim, Hebrew poets who composed prayers, many of which are still in use today. After the Arabs invaded in the seventh century, groups of scholars in the Galilee and Babylon, called the Masoretes, rushed to defend Hebrew from encroaching Arabic. They launched a historic project "to commit to writing every detail necessary to preserve the biblical text—an immense combination of fieldwork, textual evaluation, and linguistic analysis. It was called the masorah, or 'transmission,'" and wasn't finished until the year 1000. The resulting system of pronunciation and chant preserved "both the living sound and shape of biblical Hebrew and the biblical text itself," the author writes. The Masoretic Bible was sent to major Diaspora centers. The oldest intact copy is in the National Library of Russia. A still older copy is the so-called Aleppo Codex that Maimonides used as the basis for his Torah scroll. Thus, writes Glinert, "they ensured that Jews across the Diaspora would study from (more or less) identical copies."

In Europe, in the tenth century, Rashi in northern France expounded on the Torah in commentaries that would become "the gold standard of Hebrew prose." In Muslim lands, during the golden age of Arabic learning between 800-1200 A.D., Jewish scholars almost all wrote in Arabic, something lamented by Saadiah Gaon (who also wrote in Arabic). Saadiah sought in his own words "to counter the charms of Arabic" by composing the Egron, a Hebrew rhyming dictionary, and The Book of Elegance of the Language of the Hebrews. And there were Jewish poets in Muslim and Christian Spain, the most famous of them Judah Halevi, who produced worldly and pious Hebrew poetry.

More surprising is that Hebrew was a preeminent language for scientific-technical literature between the ninth and thirteenth centuries. The Book of Mixtures, ca. 970, a Hebrew work on pharmacology, was Italy's first medical text in the half millennium since Rome's fall. In the ninth and tenth centuries, the medical schools of Arles, Narbonne, and Montpelier used Hebrew as their official language of instruction. "In many ways," says Glinert, "the twelfth and thirteenth centuries marked a high point of Hebrew technical literacy—spurred not just by scientific curiosity but also by a desire to compete with the literate Latin and Spanish culture emerging in Christian Spain." As late as 1518, the rector of Leipzig University, said "there lies hidden in the libraries of the Jews a treasure of medical knowledge so great that it seems incapable of being equaled by the books of any other language."

But with the successive expulsions of Jews from France, England, Germany, and Spain, Hebrew fell on hard times. "The muse seems to have flown," says Glinert, and Jews focused on the study of the Talmud and legal codes. A renewed cultural dynamism only returned in the late eighteenth century, when the Jewish Enlightenment movement (Haskalah) tried its hand at Jewish poetry and prose, even journalism. Interestingly, Glinert says that while the Jewish Enlightenment is usually credited with being the precursor to modern Hebrew prose, it was in fact the Hasidim with their Hebrew folk tales "who were reconnecting Hebrew with spoken language—and long before Zionists did."

One flaw in Glinert's book is that he shortchanges the Zionists. It's understandable in that Glinert wants to counter the simplistic view widely held among Jews that except for its sacral uses Hebrew was moribund for 2000 years until revived by Eliezer Ben Yehuda. While Glinert gives credit to Ben-Yehuda, who allowed only Hebrew to be spoken to his infant son, essentially rearing the first native speaker in over 1,000 years, he says that as a wordsmith, Ben-Yehuda only contributed about 150 words to the language. He quotes a Zionist politician who, when asked why Ben-Yehuda had achieved such iconic status, replied: "The people need a hero, so we've given them one."

This is unfair to Ben-Yehuda, whose status was not handed to him by politicians, but earned by extraordinary dedication. The simple fact was that Hebrew was dead as a spoken language. It would take Ben-Yehuda and those Jews who came in the Second Aliyah, an influential wave of immigration to Palestine from 1904-1914, to revive it as a spoken tongue. A visitor to Ben-Yehuda's home described those early Hebrew conversations between him and his wife. It was sadly rudimentary—"Pass me this. Bring me that." They had no words for the most basic items, like plate and fork. It took an extreme mindset to accomplish what they did. Certainly, no amount of Hasidic folk tales would have done it. So while written Hebrew was preserved for centuries, it was the Zionists who took up the cause of spoken Hebrew. As Glinert himself says, Hebrew had to defeat fierce competition from proponents of Yiddish, the language most Zionists spoke. The so-called language wars threatened to tear the Zionist movement apart from within. It was Ben Yehuda and his acolytes who waged and won that war on behalf of Hebrew.

Glinert has written a scholarly book designed for and accessible to the layman. In a brief 250 pages he succinctly and convincingly demonstrates that through the centuries Hebrew was more living than dead. He says Hebrew's revival as an everyday tongue is "perhaps the only known case of the total revival of a spoken language." Today, Glinert points out, an Israeli teen can read three-thousand-year-old biblical prose with barely any help. No English speaker, or for that matter, European speaker, can say the same. And, although Glinert does not mention this, it's startling to realize that there are now more Jewish Hebrew speakers in the land of Israel than there were in the time of Jesus, when Aramaic had largely replaced Hebrew as the common tongue.