The Iranian nuclear deal reached in Vienna contains no reference to the Parchin military facility where most of Iran’s past nuclear arms-related work was carried out.

Additionally, the draft agreement made public on Tuesday contains no stated limits on Iran’s Russian-made Bushehr nuclear power facility that analysts say could produce plutonium for dozens of bombs.

Also, the accord will lift international sanctions on several Iranian entities currently engaged in supporting terrorism and building ballistic missiles, including the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC)-Air Force Al Ghadir Missile Command.

The Tehran-based command is a key element in developing nuclear-tipped missiles and is considered to be in operational control of Iranian missiles.

The lifting of sanctions in eight or fewer years will also include removing sanctions on Parchin Chemical Industries—a firm involved in the past in Iranian ballistic missile and chemical explosive work that was possibly related to nuclear arms applications.

United Nations arms sanctions blocking military sales to and from Iran will be lifted in five years under the deal, and sanctions prohibiting sales of ballistic missiles to Tehran will end in eight years. U.S. restrictions will remain.

Iran and some non-Iranian participants in the Vienna talks had pushed for immediate end to both arms and missile sales.

China and Russia, however, could begin selling arms to Iran covertly right away. Both nations have done so in the past.

President Obama praised the accord as a comprehensive, long-term deal with Iran "that will prevent Iran from obtaining a nuclear weapon."

"This deal demonstrates that American diplomacy can bring about real and meaningful change, change that makes our country and the world safer and more secure," he said, vowing to veto any legislation blocking the agreement.

A separate agreement between the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and Iran was signed yesterday and will seek to resolve past Iranian nuclear arms work in the next three months.

Yukiya Amano, the IAEA’s director, announced Tuesday that what he termed a "road map" accord on disclosing past military activities was signed with Iran. "The road map provides defined steps for clarifying all outstanding past and present issues over the next few months," he said.

Secretary of State John Kerry said the agreement will include stringent verification. "If Iran fails to comply, we will know it, because we're going to be there," he said.

However, Iran has been building its nuclear program for years despite international monitoring and the work of U.S. intelligence agencies.

Thomas Moore, an arms control specialist formerly with the Senate Foreign Relations Committee staff, said that allowing the IAEA to draw a final conclusion on past Iranian military work over the next three months is misguided.

"The IAEA’s resolution of the possible military dimensions of Iran’s nuclear program should precede the deal, not by months but by as much time as it takes to verify the absence of Iran’s [past military work], including the full historical picture of its program," Moore said. "And the deal does not do that."

On the lifting of arms sanctions, Fred Fleitz, a former CIA analyst, State Department arms control official, and House Intelligence Committee staff member, said the deal will permit Iranian rearmament.

"Language on lifting conventional arms and missile embargoes is very weak," Fleitz said.

"The IAEA simply has to certify that Iran isn’t currently engaged in nuclear weapons work to lift these embargoes early. The IAEA will be hard pressed to find evidence of this and will probably issue a report allowing these embargoes to be lifted early."

On the nuclear power-generating Bushehr reactor, Henry Sokolski, director of the Nonproliferation Policy Education Center, said that leaving it out of the accord was a mistake.

"That reactor can produce enough plutonium for dozens of bombs per year," he said. "Iran could remove the fuel from the reactor and use a small, cheap reprocessing plant to extract plutonium, and get its first bombs in a matter of weeks."

Administration officials have claimed that one of the main benefits of the deal is that it will increase the amount of time Iran would need to build nuclear arms from the current several months estimate to one year.

The 159-page Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, or JPCOA, outlines the steps Iran will take to curb its illegal uranium enrichment program.

After those steps are taken, the plan explains how the United Nations, the United States, and Europe will lift sanctions and other penalties imposed after Iran violated its agreement to follow IAEA controls on its nuclear program in the early 2000s.

A review of the agreement indicates that it contains many loopholes and vague provisions that could make final approval by Congress over the next 60 days difficult to achieve.

For example, the agreement includes several references to Iran’s "voluntary" compliance with the terms of the accord, as opposed to mandatory steps. It also sets up a bureaucratically cumbersome process for dealing with violations and noncompliance.

One section of the accord also appears to provide Iran a way to avoid fully declaring past military activities. It states that Iran "may propose to the IAEA alternative means of resolving the IAEA’s concerns that enable the IAEA to verify the absence of undeclared nuclear materials and activities or activities inconsistent with the JCPOA at the location in question."

The specific omission of Parchin is likely to be one main focus of congressional efforts to examine the agreement.

Iran, during the past 20 months of nuclear talks, refused to permit inspections of any military facilities and won that concession in the final accord announced Tuesday.

The Vienna agreement requires Iran to disclose its nuclear arms work in the IAEA-approved report, formally to be called the "Roadmap for Clarification of Past and Present Outstanding Issues," that by implication will address the concerns about Parchin contained in the November 2011 IAEA report.

Under the agreement, Iran must provide the disclosures by Oct. 15, and then the IAEA director will produce an assessment of the "resolution" of past nuclear arms work by Dec. 15 "with a view to closing the issue."

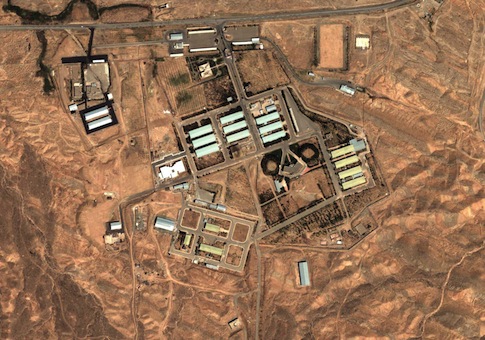

Parchin is a large military complex located about 19 miles southeast of the Iranian capital of Tehran.

It is run by the Defense Industries Organization of Iran, and includes hundreds of buildings and test sites used for the development of weapons, including rockets and fuel, and high explosives, including plastic explosives.

The agreement also lists three Iranian entities that will be freed from international sanctions after the IAEA clears Tehran of past nuclear arms work. They include the IRGC air force, the IRGC Qods Force, and the Al Ghadir missile command.

The Qods Force is Iran’s Islamist military and covert action force that has been engaged in backing terrorism.

The Qods Force is regarded as the main foreign policy tool for special operations and terrorist support to Islamic militants, including Hezbollah and the Taliban.

Administration officials said in a phone briefing for reporters that future U.S. sanctions relief will be limited and will not be lifted on measures targeting Iranian terrorism support or human rights violations.

Details of nuclear weapons work carried out by the Iranians at Parchin were revealed in IAEA reports since 2011. A November 2011 report said non-nuclear high-explosive tests were conducted at a Parchin facility that simulated the blast used to create a nuclear detonation.

The agency report said there had been "strong indicators of possible weapon development." The suspicious activity included "modeling of spherical geometries, consisting of components of the core of a [high enriched uranium] nuclear device subjected to shock compression, for their neutronic behavior at high density, and a determination of the subsequent nuclear explosive yield."

In 2012, the IAEA reported that Iran had constructed a large explosives containment vessel for "hydrodynamic experiments." Those experiments are used in testing conventional explosives that create pressure on fissile material to initiate a nuclear blast.

As recently as February, another IAEA report outlined suspicious nuclear activity at Parchin, including vehicles, equipment, and construction materials at the site.

Iran has refused IAEA requests to inspect the site since 2012, when Tehran was first questioned about the facility. Satellite photographs after 2012 revealed that some areas were destroyed in an apparent bid to cover up the nuclear arms-related work.

A classified State Department cable dated Sept. 2, 2008 stated that China exported an industrial centrifuge to a company known as the Sara Company.

"Our information indicates that the Sara Company is associated with the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran (AEOI) and has procured items from other Chinese firms in the past on behalf of Iran's Defense Industries Organization (DIO) and for the DIO subsidiary Parchin Chemicals Industries (PCI)," the cable, made public by Wikileaks, states.

Marie Harf, spokeswoman for the State Department, told reporters April 3 when asked whether Parchin would be inspected under the nuclear deal: "Well, we would find it, I think, very difficult to imagine a JCPA that did not require such access at Parchin."

Most of the agreement reached in Vienna spells out how Iran will be allowed to continue research and development on uranium enrichment and will be allowed to keep 5,000 centrifuges and a small stockpile of low-enriched uranium.

After 10 years, restrictions on uranium enrichment will be lifted and Iran will be permitted to carry out the work using more advanced design centrifuges.

The accord states that "Iran reaffirms that under no circumstances will Iran ever seek, develop or acquire any nuclear weapons."

The main implementation and monitoring unit will be a Joint Commission made up of one representative from Iran, and one each from the six states that negotiated the deal: the United States, China, Russia, Germany, France, and the United Kingdom.

The commission will address all compliance and verification issues, and matters of dispute will be settled through a majority vote of members. That lineup gives the four western powers a majority stake in dealing with contentious issues.

A senior offical in the Obama administration who briefed reporters on the Iran deal said that it "meets all the president’s bottom lines with respect to preventing Iran from being able to develop a nuclear weapon."

A second official said the deal has "unbelievable and really extraordinary and unprecedented transparency measures."

Officials defended the plan to lift "secondary" nuclear-related sanctions, which will permit Iran in the future to import military goods and ballistic missiles.

This official said that other measures will remain in place, based on both U.N. sanctions and U.S. arms non-proliferation measures that will restrict Iran from shipping arms to Yemen, Iraq, Lebanon, Sudan, Libya, and North Korea.

"We have executive orders that allow us to target those who are moving missile technologies or other things that present a proliferation concern," the official said.

Officials sidestepped questions about lifting sanctions on the Qods Force and its leader, Qasem Suleimani.

"We will continue to have significant sanctions on the Quds force and their related entities," the official said.

IAEA monitoring will include a "long-term presence" by up to 150 inspectors. Uranium mines will be watched for 25 years, and stockpiled centrifuges will be monitored for 20 years.

"Iran will not engage in activities, including at the R&D level, that could contribute to the development of a nuclear explosive device, including uranium or plutonium metallurgy activities," the accord states.

A U.N. Security Council resolution is planned that will endorse the agreement and lift U.S. nuclear sanctions. The European Union and United States will also lift sanctions imposed on Iran after the illicit uranium enrichment.

The move will allow Iran to gain access to more than $100 billion in frozen funds that critics say will be used by Tehran for building up its military forces and supporting terrorist and insurgent groups.

Iran is a main supporter of Hezbollah and is backing Houthi rebels seeking to take power in Yemen. Iran also is backing the Syrian regime of Bashar al-Assad.

The accord also prohibits the U.S. president from imposing new nuclear-related sanctions on Iran and states that Iran will consider any new sanctions for nuclear-related issues as "grounds to cease performing its commitments" under the accord.

Eight years after the agreement is in place—or per an assessment from the IAEA, earlier—the United States and the EU will lift arms sanctions on Iran, allowing Tehran to import and export conventional arms and ballistic missiles.

According to Annex 1 of the agreement, after 15 years, Iran may reprocess spent fuel, and build plutonium and uranium from spent fuel.

Significantly, after 15 years, the agreement’s ban against allowing Iran to "engage in producing or acquiring plutonium or uranium metals or their alloys" and to conduct research and development "on plutonium or uranium (or their alloys) metallurgy, or casting, forming, or machining plutonium or uranium metal" will cease.

After 10 years, the limit on 5,060 centrifuges in 30 cascade units at Natanz will end, and the ban on uranium enrichment of no more than 3.67 percent ends after 15 years. Enrichment of 20 percent is needed for nuclear bombs.

The Fordow Fuel Enrichment Plant will be converted to a nuclear physics and technology center.

Iran’s stockpile of low enriched uranium will be limited to 300 kilograms. The stockpile could be used in covert efforts by Iran to produce highly enriched uranium for bombs, if IAEA monitoring is circumvented.

After eight years, Iran will be allowed to begin producing up to 200 partial advanced centrifuges per year, and two years after that it may build complete advanced centrifuges.

"Ultimately, this is a gamble on Iran not wanting to make bombs," said Sokolski. "If they really don’t, the deal will work. If they do, the fine print won’t stop them."