"Oh! We're in a whale," said my friend as we walked into the theater to see David Catlin’s adaptation of Herman Melville's Moby Dick. The stage is set with a white skeletal structure that suggests the great ribcage and jawbones of the massive sea monster, with us inside. From the start, we are an audience of Jonahs waiting for deliverance in the dark belly of the beast.

Moby Dick is a story told by Ishmael, a sailor on the whaling ship Pequod. The crew sets out on a doomed three-year voyage, led by the august yet terrifying Captain Ahab. Ahab is consumed by his desire for revenge against Moby Dick, the seemingly unkillable white whale who cost Ahab his leg and, it seems, a piece of his soul.

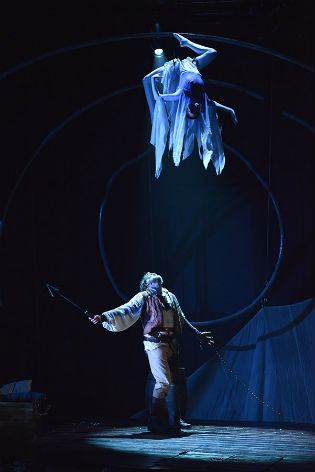

This production was done in concert with the Actors Gymnasium, an institution that specializes in aerial and acrobatic stage work. The cast of Moby Dick spends much of the play aloft, shimmying up the masts, jumping from platform to platform, suspended in the air, twirling and inverting with ropes to imitate drowning, nightmares, tempests, madness. Many of the play's best moments are wordless and dancelike, and the movement lends an air of spontaneity and danger to the production.

Catlin's production, while sometimes veering into the hokey, is often moving and provocative. Ishmael (Jamie Abelson) is the philosopher-narrator, the glass through which our story is refracted. Anthony Fleming III as the dashing cannibal king Queequeg gives the play warmth and heart. Christopher Donahue's Ahab is played with a few too many clichéd pirate tropes (arr!) to be his own man, but he's not off-putting. Melville's famous characters come to life easily; the rest of the book is harder.

To adapt a symbolism-rich text like Moby Dick, the actors must make their bodies into metaphors. To accomplish this, Catlin has added three new roles to the story, a group of women billed as The Fates (Kelley Abell, Cordelia Dewdney, and Kasey Foster). This coven of red-headed, pale-faced women in period-appropriate hoop skirts grow in presence and significance as the play goes on. At first they are the wives and mothers of the sailors, mourning and waiting, left on the shore. Then they become shanty-singing sirens, luring men to their doom. And then they are the sea itself—their hoop skirts expanding to become waves, filling the whole stage, embracing the drowning men.

The sea, often worshipped as a god, is something man conquers through skill, intrepidness, and good fortune. There is something beautiful in man's overcoming of nature. It gives us art and science. It gives us the chance to expand the limits of what is possible for human beings, to explore more, to know more, to see further. But this struggle against nature often requires us to act barbarously.

Catlin illustrates this nicely in a scene where the crew catches a whale. In the ocean, Catlin portrays the whales largely through suggestion (a spout here, the rocking of the boat by an invisible force), making them seem immense—too big to be comprehended by the eye. But when the Pequod's crew catches a whale and drags her to the deck of the boat, it's just one of the Fates, looking much smaller and vulnerable than we expected. When they string her upside down by her feet and butcher her, we see the savagery that is required to build civilization—to burn lamps and make all those objects, like corsets and pipes, that separate us from the animals.

Melville was heavily influenced by Shakespeare. When his novel is put on stage, the resemblance is all the more striking. In one scene, Ahab contemplates his harpoon while his first mate, Starbuck (Walter Owen Briggs), contemplates killing Ahab, committing mutiny, and sailing home. Side by side on stage, this is Macbeth's dagger speech and Hamlet's speech on killing Claudius mashed together. Conscience makes a coward of Starbuck, too—when he lets Ahab live, his and the crew's fates are sealed.

Ahab's desire for total mastery and his belief in his own invincibility put him in the mold of the Scottish king, admirable yet terrible. Ahab is possessed by grand ambition. We know it is wrong, and yet it is so much more sublime than Starbuck's desire for home, good pay, and safety that we cannot help but find Ahab magnetic—until it is too late.

We spend the play waiting for the great white whale to appear, and its first appearance does not disappoint. The novel dwells on the eerie "whiteness of the whale," and the theater makes impressive use of nearly-blinding white lights to disorient the audience, as the desperate sailors must have been, when the creature first rears its head.

But, as in every horror movie, anticipation of the monster is worse than seeing the thing itself. After the initial shock, the climax of this production fizzles and is almost ridiculous. Although the illusion doesn't quite carry all the way through, the novel's brutal conclusion is still disturbing, even for those who are seeing this battle for the first time.

Catlin's production is timely, reminding us that our own institutions—our vessels of peace and flourishing—are built things, and therefore destructible. Melville's moral universe is a dark one, where the highest law is "the universal cannibalism of the sea; all whose creatures prey upon each other, carrying on eternal war since the world began." The wild chaos of the ocean, the state of nature, was here before us and it will be here after us, Melville says. It waits for us. And you who dwell blithely on boats, beware.