The National Museum of American History, located in a brutalist bunker writ large, has a reputation for exhibits that are either incomprehensible or boring. For most of the years since its founding, its curators have subscribed to a modish view of a national museum as a place for "social history," which in practice involves combing the collection for the most quotidian objects available, trotting them out, and imbuing them with deep, politically correct significance. The public has not found these conditions attractive, and attendance has long lagged behind the other "Big Three" museums on the Mall—Air and Space and Natural History.

More recently, things have been looking up. A renovation allows the occasional ray of light into the lobby, and interested philanthropists have been semi-successful at establishing the notion that a good exhibit is not one that requires an undergraduate degree to understand and a postgraduate degree to enjoy.

In the Museum’s newly renovated ground floor West Wing is a new exhibit: Fantastic Worlds: Science and Fiction 1780-1910, a look at the Victorian era’s impact on the development of genre fiction. The exhibit room is cramped, dimly lit, U-shaped and tricked out in 1970s earth tones. The effect is reminiscent of a well-funded suburban library recently fallen on hard times. The principal visual attractions are a scale model of an aerodrome (an aircraft that flaps its wings), built by the Smithsonian, that crashed a few days before the Wright brothers’ successful flight at Kitty Hawk, along with a mechanical proto-computer. Arranged around the walls in seven displays are themes from Victorian-era society that correspond with forerunner concepts of genre fiction: Terra Incognita, The Age of the Aeronaut, Infinite Worlds, Rise of the Machines, Sea Change, and Underworlds.

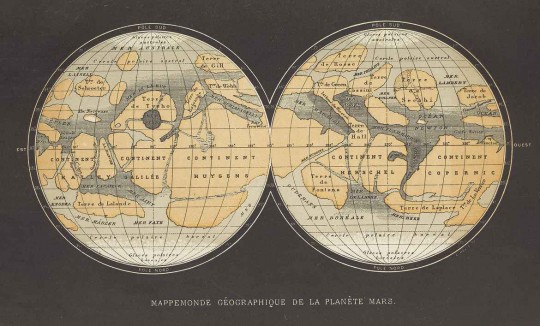

Books, maps and drawings make up the majority of each display, which is sponsored by the NMAH library. There are nonfiction volumes, like travelogues or scientific treatises, arranged with fiction on a similar topic. For example, Terra Incognita juxtaposes Dr. Livingstone’s personal narrative of his time in Africa with H. Rider Haggard’s King Solomon’s Mines. The editions the Museum displays dispel any notion that non-textual inclusions are a modern innovation. In fact, older books are richer in maps, props, and other narrative aids than trade volumes today, in spite of enormous advances in printing technology. Narrations of strange countries, some of them exaggerated, others rigorously accurate, prepared the popular imagination to accept other secondary worlds, beyond the already rich mythology of the West.

For an exhibition on the Victorian Era, which was as rife with crackpots, pseudoscience, and wild speculation as any other period in history, the textual explanation is curiously anodyne. This description of the artistic development of Mary Shelley, whose novel Frankenstein is a gut-shot criticism of untrammeled scientific exploration, is a representative example: "Her association with Percy Shelley and their literary circle further enriched her exposure to the thoughts and issues of the day, both literary and scientific." A-plus work from the high school yearbook team, to be sure.

The studied blandness is all the more surprising when you consider that the spirit of the era was so colorful, not to say alien to our own. Language for a handbill advertising a talk by Dr. Livingstone is a hint of the pathology of the age: "…the Christian philanthropist cannot but lament amidst this GRANDEUR OF NATURE humanity should be sunk in wretchedness and degradation and must look forward with hope for a better and brighter future time for the benighted children of Africa." More than anything else in the exhibit, that line encapsulates the spirit of the time and the people, the full measure of their optimism and self-righteousness.

Old books in bad light are a thin gruel for press-ganged middle-school-aged tourists. Even so, readers interested in the roots of science fiction and fantasy will find a great deal on which to reflect.