What is it about France’s Third Republic—the period between two defeats at the hands of the Germans, the first at Sedan in 1870, and the second everywhere in 1940—that so captivates the American middle class imagination? Of course Americans who yearn to visit Paris one day aren’t necessarily articulating their desires with this historical terminology. But the stereotypes and images of the France they want to see, nine times out of ten, are products of either the Belle Époque and the cleanly Haussmannized 8th Arrondissement, or—for those with a more literary bent—the period after the First World War when Scott and Zelda and their lot took advantage of the weak franc to live it up on the Left Bank.

You can see it in the movies, where the exceptions prove the rule in a very direct way: the Parisian landscape of Gene Kelly’s An American in Paris, ostensibly set after the Second World War, is based on a piece of music composed in 1928, and visually is a fantasy of boulevards and cafes and manners based loosely on the era that preceded the war. Ditto every Hollywood romantic comedy set in Paris: France and its capital have of course changed in many ways since 1940, but Americans are mainly interested in the bits that remind them of what came before. Whole films have been made about this period’s strange, nostalgic twitch upon the bourgeois thread. Woody Allen’s feather-light Midnight in Paris follows Owen Wilson into a fantasy of Lost Generation Paris, where he encounters Marion Cotillard, who longs for her own dream of the Belle Époque when she’s not occupied with bedding Corey Stoll’s Hemingway.

The same nostalgia applies to art museums: galleries featuring the Impressionists or the early Cubists are always crammed with humanity in a way that rooms holding Rococo or French neoclassical paintings are not. This applies to special exhibits, too—the National Gallery’s show on Gustave Caillebotte, which opened this week, was packed on the day of my visit, and will surely remain so. This despite the fact that—as Michael Sheen’s gratingly pretentious character happens to point out in Midnight in Paris—Caillebotte "is an artist whom I personally feel was underrated." Indeed, few casual fans of Impressionist painting—the sort who had a poster of a Monet on their dorm room wall in college—would recognize the name. But as the Directors’ Foreword of the exhibition’s catalogue points out, "a string of reminders—rainy street, bizarre perspective, people walking out of the picture, umbrellas—inevitably elicits a spark of recognition and a glow of pleasure."

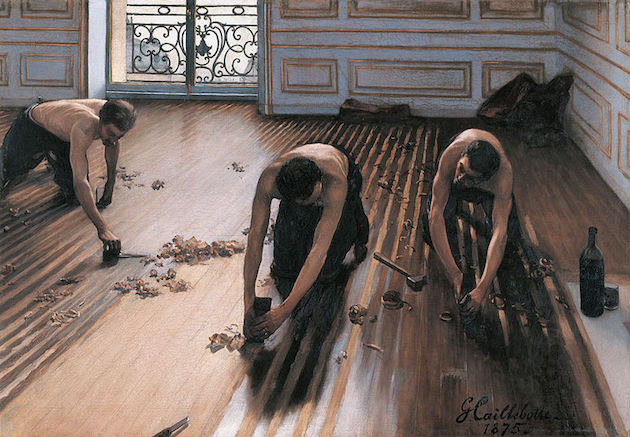

Caillebotte began exhibiting his work in the 1870s. His unconventional ‘The Floor Scrapers’ having been rejected by the Salon, he turned to showing his work with the painters who would come to be known as Impressionists. He was recognized by critics as a major force in the movement, and was liked or loathed by them accordingly. Zola disapproved, finding him too conventional in his finished brushwork—a stylistic element of which more conservative critics approved, even while they deplored his odd, pseudo-photographic perspectives, which often seemed to enlist the viewer into the painting, casting one in the role of a flâneur who happens to see a realistic scene from an incidental, subjective, and often non-ideal angle.

So why, despite his manifest talents, has Caillebotte’s reputation not kept up with those of Monet or Degas? For one thing, he was rich, and so didn’t have to work as much. The money had been accumulated by Gustave’s father, who had gone into business selling camp beds to the army. Caillebotte had other interests, like stamp collecting, boating, and gardening, which occupied much of his time. When he did paint, he produced a lot of dross, and stylistically he evolved over the course of a brief career (he died at the age of 45) from a painter who sometimes seemed to be imitating Degas to a painter who usually seemed to be imitating Monet.

His money proved essential to the nascent Impressionist movement. He bankrolled a number of important shows, loaned cash to Monet, and personally collected many of what are now considered to be the preeminent masterpieces of the period. His ‘Self-Portrait at the Easel’ shows Renoir’s ‘Ball at the Moulin de la Galette’ hanging on the wall behind him—cheekily, it hangs in reverse, because Caillebotte, in a characteristic trick, is sitting there painting himself while looking in a mirror.

After Caillebotte’s death, many of his own best paintings remained in private hands, though he gave a magnificent bequest to the state, which today constitutes the beating heart of the collection at the Musée d’Orsay. Thus his reputation, by the beginning of the twentieth century, had evolved from an artist who could excite the passions of Zola into a haut bourgeois collector and dilettante who had once or twice painted something of interest.

The National Gallery’s exhibit constitutes the latest, advanced stage of what has been a long effort to revive Caillebotte’s name as a significant artist in his own right. It makes its case effectively, showing that he was at his best when, occupying the stylistic space between Degas and Monet, he discovered a melancholic, modern, and alienated visual idiom that was authentically his own.

A word of praise is due not only to the curators of this engaging exhibit, but also to the editors and contributors responsible for the catalogue that accompanies it. In an age when the printed book is thought to be dead or dying, the National Gallery of Art consistently publishes splendid, richly illustrated and humanely written volumes to commemorate its shows. The Caillebotte catalogue is a particularly fine example. Of its essays, the best is by Michael Marrinan, who writes with such persuasive elegance and depth that it is strange to consider that he is also a tenured academic in good standing at an American university.

To the extent there is a theme to this exhibit’s promotion of Caillebotte, it seems to be that he was a man in the center of things, connecting styles—Degas’ gritty realism and Monet’s sunlit landscapes—and worlds, specifically the proud, moneyed business class of his family’s 8th Arrondisement and the more revolutionary circles across the tracks of the Gare Saint-Lazare. Marrinan observes that the famous paintings of Caillebotte’s early work—‘The Pont de l’Europe’ and ‘Paris Street, Rainy Day,’ among a few others—are of scenes that the artist would have passed through each time he walked from his family’s splendid house on the Rue de Miromesnil to the seedy cafes around the Boulevard de Clichy where the permanent avant-garde was being founded.

The painters in these cafes (along with the scholars who specialize in them today) seemed to believe that what they were doing was genuinely new: the turn to subjectivity, the acknowledgement of the painting as a painting—and not as an object with any pretense to being an illusion of the thing being painted. In an important sense, though, these artists were wrong. In the visual arts, turns to subjectivity and painterly self-regard follow periods of naturalism and classical reserve like dawn follows night—Mannerism followed the High Renaissance; Hellenism followed the classical period in Athens.

The various modern trends that got their start in Belle Époque Paris were no different in their adherence to this pattern. It is true that these artists believed modern life needed to repurpose old methods, and to develop new, energetic idioms that told the subjective truth about an increasingly chaotic world. But this phenomenon is little different from, say, El Greco’s decision to repurpose Byzantine formulae to communicate the inner life of the spiritual mind, the chaotic communion of the saints and angels, during the tumult of the Counterreformation. Perhaps critics of more recent art ignore this fact in the same way that adherents of various religions tend to believe that their own faith is not subject to the historical forces and patterns that apply to other systems of belief. The thrill of the modern, of constant newness, remains our religion today, and so we grant its founders their special pleadings.

Of course, before the twentieth century, it is also the case that, just as subjective periods followed objective ones, so objective eras ultimately followed in their own turn. That does not seem to have happened in any meaningful way in the painting of the last hundred years. Fringe movements like photorealism don’t count. Although it is interesting to observe that Caillebotte, whose interest in photo-like compositions was noticed by the critics of his own day, seems to have had some influence on photorealists like Richard Estes—whose ‘Waverly Place,’ to take one example, offers a tip of the compositional hat to ‘Paris Street, Rainy Day.’

Why hasn’t the pendulum swung back? Perhaps it is something to do with the uniquely fractured age in which we live—or perhaps there is a more banal cause: the invention of photography robbed painting of its function as the primary means of realistic representation on a flat plain. To justify its own existence, painting has been left stranded in the realm of subjective representation, trapped there by an accident of technological progress.

In the mid-1870s, the very years that Caillebotte was painting his most successful Parisian scenes in the Quartier de l’Europe, Charles Marville stood in those same recently Haussmannized streets taking his now famous photographs. As far as painting is concerned, perhaps this particular time and place makes a just demand on our sense of nostalgia, as the final moment when a certain set of rules and patterns still applied.