The struggle between the United States and the Soviet Union came to be known as the Cold War because of an essay that George Orwell wrote two months after the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The piece had the folksy title, ‘You and the Atom Bomb,’ and outlined the thinking that would later condition 1984:

From various symptoms one can infer that the Russians do not yet possess the secret of making the atomic bomb; on the other hand, the consensus of opinion seems to be that they will possess it within a few years. So we have before us the prospect of two or three monstrous super-states, each possessed of a weapon by which millions of people can be wiped out in a few seconds, dividing the world between them. It has been rather hastily assumed that this means bigger and bloodier wars, and perhaps an actual end to the machine civilization. But suppose — and really this is the likeliest development — that the surviving great nations make a tacit agreement never to use the atomic bomb against one another? Suppose they only use it, or the threat of it, against people who are unable to retaliate? In that case we are back where we were before, the only difference being that power is concentrated in still fewer hands and that the outlook for subject peoples and oppressed classes is still more hopeless.

Orwell took a deeply pessimistic view of what a state that was "at once unconquerable and in a permanent state of ‘cold war’ with its neighbors" would look like, and it is necessary to point out that the moral equivalence he anticipated between the United States, the USSR and China (the rise and nuclearization of which he predicted in the essay) did not come to pass. Additionally, it is hardly that those states made a "tacit agreement" not to use their weapons—they were simply terrified of the likely consequences of doing so.

Those points conceded, it is remarkable how much Orwell gets right, and how a journalist and novelist writing in late 1945, while the rubble was still more or less smoking all across the world, could lay out something very much like the coming logic of the Cold War.

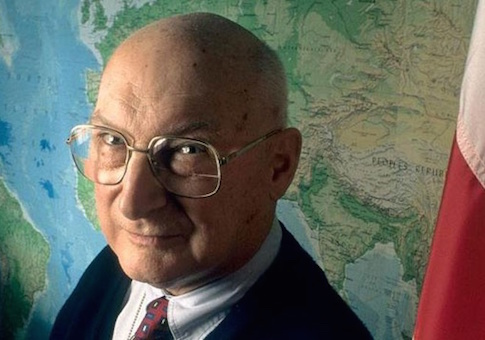

Into this war, and logic, arrived the young Andrew Marshall. As Andrew Krepinevich and Barry Watts describe in their interesting and admiring biography, ‘The Last Warrior: Andrew Marshall and the Shaping of Modern American Defense Strategy,’ the Pentagon’s future "Yoda" (Marshall finally announced his plans to retire from the Pentagon last year, at the age of 93) had a Greatest Generation upbringing, scenes from which could be depicted admiringly in a Ken Burns documentary. Immigrant parents, Midwestern upbringing, kept out of the military by a heart murmur but working away in a plant producing wings for B-17’s and B-29’s (did the Enola Gay’s wings pass down his line?) but not allowing himself to fully starve a voracious habit for reading—the prologue to Marshall’s career as a defense strategist was remarkable, but so were the youths of most men born in America in the 1920s.

The career that followed turned out to be exceptional and strange. After familiarizing himself with the ways of economists at the University of Chicago, he went to work at RAND, hired initially to help with a study investigating the question of whether or not increasing rates of psychosis would cause problems for the military draft in the likely event of war with Russia. From there, he became involved in a series of projects that used the analytic tools of economists and social scientists to determine the best ways to fight the Soviets.

In the early days of the Cold War, when America had a decisive lead in the number and net destructive capacity of nuclear weapons, it was considered likely that, when the war came, it would involve a limited nuclear exchange. It took quite a few years, and the recognition that both superpowers had acquired enough weapons to, in effect, end the world, to catch the folks at RAND and elsewhere up with Orwell’s realization that the likely scenario was one in which the Bomb would never be dropped.

Developing his skills as an analyst on questions of how to beat the Russians, Marshall became preoccupied with the limits of his own art. How much could the sorts of analyses performed by RAND really tell generals and politicians about the coming war? The more Marshall considered the question, the more skeptical he became.

The same set of problems kept popping up in each project. For one, analysts tended to assume that the Soviets made decisions rationally and in a unified fashion, at the top—even though even the slightest bit of reflection on the American decision-making process revealed a great deal of irrationality and bureaucratic infighting resulting in ‘good enough’ solutions. Could the Soviets be so different? And if they were, as Marshall suspected, not supermen but bureaucrats themselves, couldn’t basing war plans on the expectation of Soviet rationality be a flawed and dangerous approach?

The rational actor bias was seductive in part because it made analysis easy. If a team at RAND had to figure out, with limited information, where the Soviets were basing their long-range bombers, they could solve the problem by simply putting themselves in the shoes of the Russians and doing whatever seemed best—in this case, deciding that the Russian aircraft would be based in the interior of the country, where it would be hard for American bombers to get at them.

But just the opposite turned out to be the case. As a consequence of bureaucratic inertia, the Soviets didn’t move their bases inland as the range of their aircraft increased, but kept them near the coast instead, as they had been required to when, early on, the planes could only fly so far.

The rational actor problem wasn’t the only recurring issue. Criteria established at RAND to determine success or failure in its rather dark "war games" were often arbitrary, if not quite bizarre, with analysts effectively weighting the retention of a few burned-over miles of West Germany from the Red Army as being more important than the loss of, say, 10 million men, women and children in North America.

What was "winning" in the nuclear age, anyway? Static comparisons of weapons caches revealed very little about the dynamics of what Marshall increasingly expected to be a long—for planning purposes, an effectively endless—struggle.

Krepinevich and Watts—former staffers for Marshall when he later worked at the Pentagon—provide an interesting account of these years, even if much of the material they clearly want to cite remains classified, a problem that continues throughout the book. Another of the book’s shortcomings seems to be that you can take the defense bureaucrats out of the Pentagon, but you can’t take the bureaucracy out of their prose:

Hitch asked Alan Enthoven, who had left RAND for the Pentagon in 1960, to set up an Office of Systems Analysis (OSA) within Hitch’s office. OSA’s purpose was to conduct cost-effectiveness studies aimed at quantifying alternative ways of accomplishing various national security objectives so that senior decision makers could understand which of them contributed the most to a given objective for the least cost; that is to say, those that were the most cost-effective.

Presumably readers of a biography of one of the most prominent defense bureaucrats of the last century will have an interest in bureaucracy and a tolerance for bureaucratese. More frustrating is the tendency of the authors to soften their punches with thick gloves of vague and euphemistic language, as when—a few paragraphs after that quoted above—they describe how the military resisted the OSA’s work because its "key investment choices" sometimes went against "vested interests" and the judgments of "senior military leaders." Which key decisions? Which interests? Which leaders? The debate in question occurred fifty years ago. Whose feelings are we trying not to hurt?

After two decades rising through the ranks at RAND, Marshall was brought to Washington by Henry Kissinger, initially to consult at the Nixon White House and finally to the Pentagon, where he founded the Office of Net Assessment in 1973. He quickly found himself involved in arguably the key defense controversy of his day—and, perhaps, the most important internal debate of the Cold War: Just what proportion of their economy were the Soviets spending on their military?

Most agreed that Soviet military spending was vast, but there was substantial disagreement (that soft, lilting bureaucratese is so seductive!) on how big the Soviet economy was. This became known as the "denominator problem." If, as the CIA believed, the Soviet economy was huge, then the Russians would be able to support their military expansion indefinitely, leading to the inevitable policy conclusion, favored by Kissinger and later Ford, of détente.

But if the Soviet economy were smaller than estimated, it would be possible to provoke them into bankrupting themselves. This was the policy ultimately favored by Reagan, the formulation of which—even without being able to refer to the still-classified documents from the period, Krepinevich and Watts make a strong case—depended heavily on Marshall. Further evidence of the point is supplied by the fact that Marshall’s (and Reagan’s) critics, who recall that hawkish period with a tone of suppressed anguish, still despise him for his role.

Playing a considerable—one might joke, a measurable—role in the downfall of the Soviet Union would be a decent life’s work for most, but Marshall stayed on at the Pentagon for several decades longer, a tribute to his bureaucratic skill as much as any analytic excellence. His staff—famously, and famously slavishly, devoted, they referred to their work at the Office of Net Assessment as time spent at ‘St. Andrew’s Prep’—was central, as was Marshall, to post-Cold War debates about the "Revolution in Military Affairs" brought about by precision weaponry and the information revolution, as well as planning militarily for the rise of China. Iraq and Afghanistan figure only peripherally in the book, mostly from the perspective that they interfered with Marshall’s long-term priorities.

From a procedural standpoint, Marshall’s most important legacy was his deep and abiding skepticism about the limits of the trade of analysis that he himself plied. Again and again, Krepinevich and Watts portray his role in debates as productively critical: Pointing out, for example, that if the prevailing quantitative methodology used to compare U.S. and Soviet forces in the ‘70s were applied to Germany and France in 1940, it would not predict a German victory. Social scientists often pay lip service to the limits of their art’s abilities, but it seems to be the rare practitioner who actually takes this line of thinking to its necessary conclusions, without losing faith that the art is still, in some ways, useful.

There will have to be another biography of Marshall when the key documents are one day unclassified. He often appears in the present volume as though a ghost, because, with few exceptions, the authors cannot refer to or quote from his most important writings. One hopes that his approach to analysis doesn’t depart the Pentagon with him, as Russian bombers are back on patrol and the Chinese are developing their missile technology. The major powers have not gone to war since 1945, as Orwell predicted, not because of international organizations or the moral evolution of man, but because of the thermonuclear sword of Damocles above us all.

Which, Orwell might have pointed out, is the kind of thing that works—right up until it doesn’t.