Among the many quirks of the small college where I was an undergraduate was that it required all students to read, in the summer before senior year, War and Peace. Far from being a dull project, for me the novel was a source of hypnotic delights: The competing role models of the dark, heroic Andrei and his friend, the searching, kindly Pierre; the attractive figure of Natasha—what now most holds me back from rereading the thing is the fear that, in my adulthood, I can no longer be charmed by her—not to mention the spectacle of these weirdly real souls caught up in all that war, in Great Events.

Never mind that the closest I came to an act of bravery was getting up before 10 a.m. and managing not to trip over the empties on my way to class. I decided that Andrei—tall, tragic, and irresistible to the ladies—was my kind of guy. Like preferring Achilles to Odysseus, or James Bond to George Smiley, this was a lifestyle choice. I expect a lot of young men who read the novel have a similar reaction, though I don't know how many had a professor like mine, who delicately pointed out how my preference revealed that I was completely missing Tolstoy's point. The ambitious Andreis of the world are very often incapable of happiness, he told me. It's the bumbling Pierres who, despite appearances, really live.

I relate this story not because my moral education is all that interesting, but to make the more general point that a novel—a great novel, at least—really can be a source for such an education. That's a commonplace enough assertion in some circles, though not, sadly, in most college literature departments today.

At least it would be supported by Gary Saul Morson, who has somehow not only survived but flourished as a professor of Russian literature, first at the University of Pennsylvania and today at Northwestern, and who came to Washington this week to deliver a lecture at the Heritage Foundation called "Pray for Chekhov: Or, What Russian Literature Can Teach Conservatives." (It was quite excellent, and you can watch it here.) Morson would go much further, in fact. Western intellectuals, in his view, increasingly resemble the pre-Revolutionary Russian intelligentsia. Considering the totalitarianism that resulted when these men and women finally took power, this is not a reassuring observation. Morson warns:

Let me lay my cards on the table. To the extent that a group of intellectuals comes to resemble an intelligentsia, to that extent is totalitarianism on the horizon—should that group gain power. That, not Swedish style social democracy, is what I see happening here. I foresee in years rather than decades first a Putin style managed democracy, and soon after a Stalinist state, or rather one beyond Stalinism since Stalin did not have access to today's monitoring technology.

The old intelligentsia—united, like today, by faith in materialism, socialism, and the power of science to order human affairs—found its enemy in literature, and in particular in the great realist novelists. Morson quoted the critic Mikhail Gershenzon's line that "The surest gauge of the greatness of a Russian writer is the extent of his hatred of the intelligentsia," and indeed the novelists generally took a dim view of their politicized intellectual contemporaries. At least one, Dostoyevsky, himself once a member of the intelligentsia, accurately predicted the logic of the twentieth century's coming totalitarianism—for example, in the reasoning of Crime and Punishment's Raskolnikov, who opportunistically shifts between utilitarianism and relativism to justify his crime.

The real divide between the intelligentsia and the novelists was that the former were invested in all-encompassing ideologies of History and human action, while the latter, as documentarians of the complexity of man's consciousness and the radical contingency of the actions of men in groups—of "history"—found ideology ridiculous. The novelists, through their very method, were "making a polemical point," according to Morson. "The intelligensia denied that people were complex at all. Human complexity was an idea hindering radical action." The realists stood in their way.

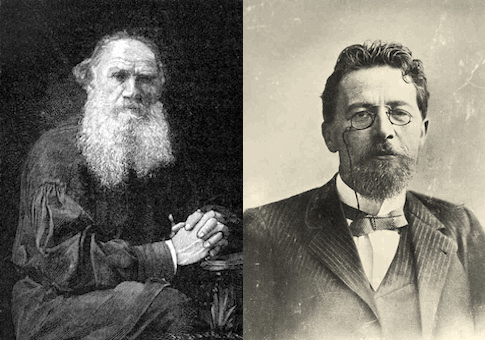

This was literature that stood not so much in opposition to philosophy, but offered itself as a replacement to philosophy—or at least, to modern philosophy, and to the social sciences. It was humanizing, pluralistic, and implied that one's politics ought to follow from a sense of modesty regarding what man can know, and of what he can achieve. It was, in this sense, conservative. Some of the realists—most prominently Tolstoy and Chekhov—also advanced an ethics that paired nicely with this politics: life was to be found in the unheroic moments between crises, and bourgeois concerns like treating your family well and paying your debts were tied to happiness.

I am not sure that Morson is right that we are on the path to totalitarianism. As he himself points out, the Russian radicals of the nineteenth century were revolutionists. Our radicals, bless them, seem too invested in bourgeois concerns like tenure to follow their own project to its logical ends. But his eloquent case for literature, and in particular for the realists, is of great value. It also highlights an enduring problem for conservatives: How do you interest the young in the case for modesty and incrementalism? How do you warn them of the dangers of heroism?