Funding provided by federal grants appear to have supported efforts to lobby state and local governments for greater restrictions on tobacco sales and usage in violation of restrictions on the use of federal funds for political or policy advocacy.

The revelations are fueling criticism of the Obama administration’s efforts to tamp down on obesity and tobacco use. Critics say those efforts have routinely included illicit uses of federal funds.

The latest alleged violations occurred at the Corporation for National and Community Service (CNCS). The agency’s Social Innovation Fund, created by the 2009 Edward M. Kennedy Serve America Act, has granted millions to nonprofits around the country.

Among grant recipients is the Missouri Foundation for Health (MFH), a large nonprofit "dedicated to improving the health of the uninsured and underserved" in the Show-Me State.

MFH received nearly $3 million from 2010 to 2012 for its Social Innovation Missouri program, which was created to administer CNCS funds, and helped built coalitions to enact additional restrictions on tobacco use in the state.

It has been a powerful force in that effort, its allies say.

"The Missouri Foundation for Health was seen as a leader in the tobacco prevention and cessation initiative, education, and working with smoke free coalitions," wrote the Healthcare Foundation of Greater Kansas City in 2012.

The foundation’s and its allies’ work produced tangible results. Missouri still does not have a state-wide indoor smoking ban, but a number of municipalities have instituted such bans since MFH received its federal grant.

While MFH was also aiming for statewide policy changes, legislative victories in general are major benchmarks of the success of its Social Innovation Missouri (SIM) program.

"Measurable outcomes of SIM include … increased healthy policy changes in targeted communities," according to MFH’s page on the Social Innovation Fund website.

"The intent [of Social Innovation Missouri] is to increase access and support, and encourage tobacco-free policy implementation and tobacco control by engaging the community and fostering policy change in the target population," the group wrote.

MFH is a 501(c)(4) nonprofit, meaning it can engage in lobbying activities. However, federal law prohibits lobbying organizations from receiving federal funds.

MFH has not reported any lobbying expenditures in the past 10 years, but observers say other laws preclude the type of policy advocacy in which MFH and its subgrantees are engaged.

MFH and all other Social Innovation Fund grantees were required to certify in writing "that no funds received from CNCS have been or will be paid, by or on behalf of the applicant, to any person or agent acting for the applicant, related to activity designed to influence the enactment of legislation, appropriations, administrative action, proposed or pending before the Congress or any State government, State legislature or local legislature or legislative body."

That language mirrors regulations at CNCS and guidance issued by the White House Office of Management and Budget on the use of federal grants for lobbying or advocacy work.

OMB prohibits the use of such funds for "any attempt to influence the introduction of Federal or State legislation; or the enactment or modification of any pending Federal or State legislation through communication with any member or employee of the Congress or State legislature."

CNCS general counsel Frank Trinity reminded agency employees in 2007 that they and CNCS grantees "may not attempt to influence legislation…if they are doing so while charging time to a Corporation-supported program…or otherwise performing activities supported by the Corporation."

Despite these prohibitions, MFH frequently promoted policy advocacy as integral to its Social Innovation Missouri program.

A major goal of the program, according to an MFH solicitation for subgrantees, was "modifying policy language and assisting in navigating bureaucratic hurdles to policy change."

Subgrantee applicants, the solicitation said, should propose strategies for "advocating for healthy policies so people are encouraged to make healthy choices."

"Lasting policy changes also have a significant impact on tobacco use and obesity prevention, and are critical components of program," MFH wrote.

The solicitation was careful to note prohibitions on policy advocacy.

"These funds cannot be used for lobbying activities," the solicitation noted. Other language in the solicitation suggested there may be some wiggle room on that prohibition: "Rules governing lobbying and advocacy are complex and subject to interpretation."

The Missouri Foundation for Health did not respond to requests for comment on allegations that it violated those restrictions.

A key guide of MFH’s activities was created by the group Americans for Nonsmokers’ Rights, which MFH lists as a "collaborating partner."

ANR’s 501(c)(4) activist arm calls itself "the leading national lobbying organization dedicated to nonsmokers' rights" and says it "pursues an action-oriented program of policy and legislation."

MFH worked with its 501(c)(3) division, the Americans for Nonsmokers’ Rights Foundation, contributing $270,000 to the group from 2010 through 2012, according to annual 990 filings.

As part of its support for Social Innovation Missouri, ANR and MFH collaborating partner Trailnet created a "coalition core competencies checklist" laying out all the elements of a successful anti-tobacco coalition.

The checklist features an entire section devoted to "policy advocacy." Subsections include "campaign planning and strategy," "understanding of protocol and timing for approaching elected officials," "creating a policy implementation plan and supporting the policy implementation process," and "preparing decision-makers for opposition talking points and strategies—neutralizing the opposition’s impact."

The checklist also featured a single item on restrictions on federally funded policy advocacy: "Understanding definition of ‘lobbying’ and how it relates to your campaign activities."

MFH explicitly directed its subgrantees to push for the enactment of state and local laws restricting the sale or public use of tobacco products.

"SIM grantees and partners are expected to participate in local and statewide policy advocacy activities that affect their programming goals," MFH wrote in its solicitation.

Those activities include "promoting program efforts to local media and policymakers."

The solicitation mentioned "community smoke-free policies" and tax increases on tobacco sales as worthwhile legislative objectives for subgrantees.

Dan Epstein, executive director of the government watchdog group Cause of Action, said his group investigated similar allegations of federally funded lobbying efforts financed by Obamacare and the 2009 stimulus bill.

COA dug into Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) grants through its stimulus-funded Communities Putting Prevention to Work program.

Ostensibly a "preventative health" project, CPPW "laundered money through so-called stealth lobbying coalitions, formed to skirt prohibitions on lobbying by non-profits, in order to promote local laws banning otherwise legal consumer products such as sodas, e-cigarettes, and fast food," COA wrote in a report on the program.

"We already uncovered multiple organizations around the country that illegally lobbied with federal taxpayer dollars under the Communities Putting Prevention to Work program," Epstein wrote in an email.

"We also know that entities in Missouri that received CPPW money have been offered federal funds by MFH efforts, so it is no surprise that the unchecked grant money going to MFH could now be used to violate the law again," he said.

CDC, the report said, "permitted and even encouraged CPPW grantees to violate federal law and use CPPW funds to lobby state and local governments."

Revelations about federal funding for anti-tobacco lobbying caught the attention of members of Congress and the Department of Health and Human Services’ inspector general.

CDC literature on the CPPW program "appear[s] to authorize, or even encourage, grantees to use grant funds for impermissible lobbying," wrote inspector general Daniel Levinson.

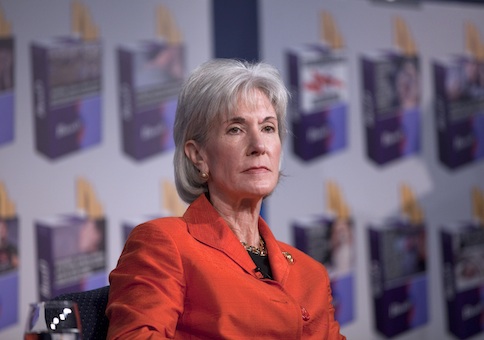

Sen. Susan Collins (R., Maine) wrote to HHS Secretary Kathleen Sebelius to express her concern that "grantees of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), under the direction of official CDC guidance, appear to have used federal funds in attempts to change state and local policies and laws."

"In response to CDC guidance, several grantees as recently as 2010 have engaged in strategies that, absent an expressed authorization by Congress, appear to violate federal law regarding influencing state and local governments to adopt laws and policies," Collins wrote.

It is not clear whether CNCS was aware of or concerned about MFH grant language that seemed to encourage subgrantees to engage in policy advocacy. The agency did not respond to a request for comment.

Missouri political observers say MFH’s work is just the most recent use of federal funds for anti-tobacco lobbying in the state.

"In Missouri, many political subdivisions use tax money directly and indirectly to influence the outcome of legislation," said Carl Bearden, executive director of United for Missouri, a free market group in the state.

"A large majority of the time they are taking positions contrary to the best interest of taxpayers but not the entity itself."

Bearden said he was not familiar with MFH’s work, but "the use of Social Innovation Fund dollars to support state and local laws against tobacco would certainly be an egregious use of those funds. A use that should be stopped immediately and those responsible be held accountable for it."

St. Joseph, Mo., is the latest battleground in the state’s tobacco policy debates, and opponents of a proposed indoor smoking ban say they have seen impact of federally funded lobbying efforts in that city.

"Of special concern is the upcoming smoking ban election in St. Joseph," said Bill Hannegan, director of Keep St. Louis Free, a group that opposes smoking bans, of a proposed ballot initiative to ban smoking in indoor public establishments.

"The illegal use of federal funds there could sway an otherwise close election," Hannegan said of the April 8 referendum.

One of the groups fighting for that referendum, Clean Air St. Joe, received funds from Social Innovation Missouri, a CASJ spokeswoman told the St. Joseph News-Press.

CASJ is currently asking supporters to contact members of the St. Joseph city council "to remind them only a comprehensive smoke-free ordinance that includes all bars, restaurants and indoor workplaces will protect the health of all workers."

CASJ works closely with the Heartland Foundation, which is also a SIM subgrantee.

Previous attempts to expose and correct the use of federal funds for policy advocacy have been unsuccessful, said St. Joseph Telegraph editor Mike Bozarth, a former member of the city council.

"Money and time provide obstacles," he said of efforts to stem the tide of federal lobbying money.

"I told local anti-ban folks they needed money and lawyers to sue over it," Bozarth said of previous efforts to institute smoking bans with federal assistance. "I don't see how these violations are allowed to stand. But again, it takes money for lawyers to challenge them."

Epstein said he does not expect the Obama administration to address these apparent violations without prodding.

"As the IRS targeting scandal reveals, this administration is clearly more concerned about private money going to nonprofit organizations, which have not violated any laws, than organizations who push administration policies while violating federal law with taxpayer dollars," Epstein wrote.

"The hypocrisy is blatant and taxpayers should demand accountability for these types of violations."