"I would remind you that extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice. And let me remind you also that moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue!" So declared GOP presidential nominee Barry Goldwater to the delight of party loyalists at the July 1964 Republican National Convention on the way to a landslide loss to President Lyndon B. Johnson in the general election four months later.

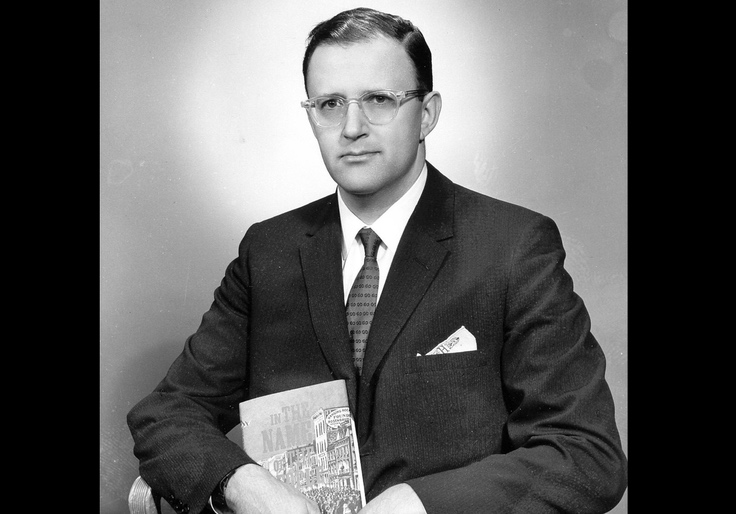

The author of Goldwater's signature lines championing extremism and demoting moderation was Harry V. Jaffa. At the time a 45-year-old professor at Claremont Men's College (renamed Claremont McKenna College in 1981), Jaffa might have seemed like an unlikely proponent of zealotry. He was the author of Thomism and Aristotelianism: A Study of the Commentary by St. Thomas Aquinas on the Nicomachean Ethics (1952) and Crisis of the House Divided: An Interpretation of the Issues in the Lincoln-Douglas Debates (1959)—two fine books on monumental figures who identified moderation and prudence as virtues essential to ethics and statesmanship. An outspoken member of the first generation of Leo Strauss's students, moreover, Jaffa would have been as knowledgeable as anyone about the limits of politics; the reality and elusiveness of justice; and statesmen's unending challenge of balancing competing principles, tempering partisan claims, and accommodating complex and changing circumstances.

At the same time, Jaffa's praise of immoderation seems to fit his character and track his influence on the persistent debate—which came of age in the 1950s and rages today—about American conservatism's core components and primary purposes. Always energetic and bold, Jaffa acquired in conservative and Straussian circles (overlapping but by no means identical) a reputation as combative and overbearing. "If you think it's hard to argue with Harry Jaffa," quipped William F. Buckley, "try agreeing with him."

Following Jaffa's death in 2015 at the age of 97, fellow Straussian Harvey C. Mansfield joked with reference to Crisis of the House Divided, "One might think it impossible to exaggerate the importance of this book if Jaffa had not shown us how." To Walter Berns, another fellow Straussian whom he had known for decades, Jaffa wrote, "In your present state of mind nothing less than a metaphysical two-by-four across the frontal bone would capture your attention." Berns spurned conciliation: "At the present time, 3,000 miles separate me from Harry Jaffa, and I'm not interested in diminishing that distance by a single inch."

Jaffa is the only Straussian to form a separate school around himself. The primary vehicle of his continuing influence on American conservatism is the Claremont Institute for the Study of Statesmanship and Political Philosophy, which proudly acknowledges its debt to Jaffa. Many Claremont fellows seem to have concluded that as in 1964, so too today: The defense of liberty and the pursuit of justice require uninhibited rhetoric and drastic measures.

Established in 1979 as an independent organization separate from the college where Jaffa taught, the Claremont Institute engages "in the battle to win public sentiment by teaching and promoting the philosophical reasoning that is the foundation of limited government and the statesmanship required to bring that reasoning into practice." The institute publishes the Claremont Review of Books, a highbrow quarterly of opinion and ideas, and the American Mind, an online magazine that provides more frequent and freewheeling commentary on politics and culture. The institute also conducts often-formative seminars on American political thought and the history of political philosophy for college students and recent graduates.

Like their East Coast Straussian brethren, the West Coast Straussians at the Claremont Institute cherish Plato and Aristotle as vital sources of living wisdom about morality and politics; honor the American founding as the decisive political achievement of the modern era and as the institutionalization of a political science that ought to guide American citizens and statesmen today; recognize the dependence of liberal democracy on tradition, culture, and education; and see in progressivism a dangerous rejection of the limited-government principles essential to the nation's freedom and prosperity.

Whereas East Coast Straussians tend to recognize enduring discontinuities between classical and modern political philosophy, West Coast Straussians are inclined to view the American founding—as interpreted by Jaffa's Lincoln—as reconciling the tensions between them. In contrast to many East Coast Straussians, moreover, West Coast Straussians press an apocalyptic diagnosis of contemporary liberal democracy in America; promulgate a critique of most conservative think tanks and publications as having sold out to, and effectively joined forces with, the progressive establishment; and, while alert to his manifest flaws, embrace Donald Trump as the best available tribune for restoring a conservatism grounded in America's founding principles and the nation's finest constitutional traditions.

In early September 2016, the Claremont Review of Books published online under the pseudonym Publius Decius Mus "The Flight 93 Election," which captured Jaffa's intellectual heirs' reverence for America as it ought to be and their repugnance at what America had become. Rush Limbaugh promptly turned the short polemic into a cause célèbre by reading it aloud on his radio show.

The cri de coeur was the work of my friend Michael Anton, whose identity the Weekly Standard disclosed to the public five months later, shortly after he joined the Trump administration's National Security Council to advise on strategic communications and speechwriting. Long affiliated with the Claremont Institute—and, since leaving government in 2018, also a lecturer in politics and research fellow at Hillsdale College's Washington campus—Anton saw America hurtling toward disaster. While "a Hillary Clinton presidency is Russian Roulette with a semi-auto," he ruefully opined, "with Trump, at least you can spin the cylinder and take your chances."

Anton heaped scorn on "Conservatism, Inc."—the network of journalists and magazines, scholars and think tanks, and political strategists and consulting firms whom he accused of joining with left-wing elites to serve as guardians of an incompetent, corrupt, and decadent establishment. In a strange echo of Barack Obama, who less than a week before his victory in the 2008 presidential election proclaimed that "we are five days away from fundamentally transforming the United States of America," Anton called for "fundamental change" in the United States to forestall the "ever-leftward" tendency of America and the West.

In his short book from February 2019, After the Flight 93 Elections: The Vote that Saved America and What We Still Have to Lose, Anton offered philosophically informed reflections on the roots of sound government, elaborated on his critique of what he regarded as nothing less than the ruinous progressive ascendancy in America and its supine conservative enablers, and renewed his call for thoroughgoing change. He concluded that the "task going forward—for those remaining conservative intellectuals who have not formally or functionally defected to the Left—is to relearn, or learn for the first time, what to conserve, why it is worth conserving, and how to conserve it." Since, in Anton's account, contemporary elites have disfigured and rendered noxious American politics and culture—which, therefore, deserve to be toppled and overcome—a better name for what he identifies as the "task going forward" as he understands it is restorationism.

In May of this year, Glenn Ellmers—like Anton, a senior fellow at the Claremont Institute and affiliated with Hillsdale College—further distanced himself from the common-sense understanding of conservatism as a temperament or outlook committed to preserving and fortifying longstanding beliefs, practices, and institutions and did so explicitly in the name of "Claremont's intellectual founder, the late professor Harry Jaffa." In "'Conservatism' is no Longer Enough," Ellmers advanced the remarkable proposition that "most people living in the United States today—certainly more than half—are not Americans in any meaningful sense of the term." Notwithstanding their formal citizenship, "they do not believe in, live by, or even like the principles, traditions, and ideals that until recently defined America as a nation and as a people." Unless conservatives manage to set aside their squabbling, he warned, "the victory of progressive tyranny will be assured." To avoid "the gulag," American conservatives "must all unite around the one, authentic America, the only one which transcends all the factional navel-gazing and pointless conservababble."

Because they have been educated about America's founding principles in the spirit of Harry Jaffa, Claremont Institute fellows, Ellmers suggests, are uniquely well-positioned to grasp how little of the legacy of the American founding remains intact or even recognizable. Therefore, "overturning the existing post-American order, and re-establishing America's ancient principles in practice, is a sort of counter-revolution, and the only road forward." Ellmers's revolutionary thesis, consistent with Anton's bleak assessment and the overall bent of the Claremont school, is that conservatives must become radicals and re-founders. To conserve American constitutionalism, they must take the lead in "introducing new orders," albeit of 18th-century American provenance.

Ellmers's new book, The Soul of Politics: Harry V. Jaffa and the Fight for America, illuminates the paradox. In his measured, knowledgeable, and scrupulously argued intellectual biography, Ellmers shows, though he does not put it this way, that Jaffa's life's work represents both an extended case for moderation and prudent statesmanship and an invitation to immoderation.

Over the course of 60 years, Jaffa published 14 books; authored numerous articles, scholarly and polemical, including a syndicated column; and dispatched to students, friends, and adversaries a multitude of letters. His leading themes will be familiar to readers of Leo Strauss: the relation between classical and modern philosophy, the tension between reason and revelation, the contest between philosophy and poetry, the battle between tyranny and freedom, and the mutual influence of philosophy and statesmanship.

Jaffa's most substantial scholarly contribution consisted in clarifying the philosophical and political significance of the principles of the Declaration of Independence and in explaining why Abraham Lincoln was their most consequential interpreter. Jaffa's most substantial political contribution involved the reorientation of American conservatism around the American founding and around Lincoln's restatement and vindication—in the face of the searing national crisis rooted in the evil institution of slavery—of the nation's founding principles. Indeed, according to Ellmers, Jaffa's writings on Lincoln—A New Birth of Freedom: Abraham Lincoln and the Coming of the Civil War (2000) extended, refined, and in some respects revised the interpretation of Lincoln set forth decades earlier in Crisis of the House Divided—were "the anchor points of his scholarship."

Crisis of the House Divided, which features a groundbreaking analysis of both sides of the 1858 Lincoln-Douglas debates as well as of Lincoln's Lyceum speech of 1838 and Temperance Address of 1842, presents a searching exploration, Ellmers writes, "of the problem of slavery within a republican form of government." According to Ellmers, Jaffa shows that, contrary to the moral relativism that prevailed in intellectual circles in 1950s America, the natural-rights principles on which America was founded might well be true; the Constitution incorporated the idea that all human beings were endowed with equal natural rights; ratification of the Constitution, a brilliant charter of government marred by the legal protection it gave to slavery, furnished a vivid and tragic illustration of the permanent tension between wise government and the consent of the governed; slavery grossly violated America's founding principles; and Lincoln should be understood as a "redeeming prophet" as well as a "philosophic statesman."

A New Birth of Freedom follows Lincoln through his election as president in 1860 and places, Ellmers writes, "the Civil War, and America itself, within a grand overview of western civilization." The many strands of the book culminate in Jaffa's stunning judgment that "the prudent form of classical Aristotelianism was already present in the founding, and that Lincoln found it there." In other words, the American regime, which tempers and enlightens self-interest through well-wrought political institutions and secures for citizens the freedom to worship as they deem best or not, join or exit communities, and pursue happiness as they understand it was not merely the best practical regime under modern circumstances but the best form of government a human being could reasonably hope to live under.

Jaffa's legacy gives rise to countervailing tendencies. On the one hand, his explorations of Lincoln's writings and statesmanship enrich understanding of political moderation by showing how his appeal to the Declaration's affirmation of equality in freedom formed an essential part of the prudent statesmanship that preserved the United States at its darkest hour and brought the nation into closer alignment with its founding promise. On the other hand, Jaffa's depiction of Lincoln as understanding the founders better than they understood themselves—which implies that those who understand Jaffa's Lincoln understand the founders better than they understood themselves—encourages the immoderate conceit that Jaffa's writings transmit an indispensable teaching to an elect few into the true character of the American political order and its fundamental requirements.

This latter tendency—which, Ellmers notes, Willmoore Kendall emphasized in a 1959 review of Crisis of the House Divided in National Review—encourages ambitious transformative enterprises. Repudiating the mass of one's fellow citizens and engineering a great revolt against contemporary manners and morals on the grounds that the principles of American constitutional government have been "blurred or destroyed" may be described in many ways. In some circumstances it may be justified. As Ellmers comes very close to saying, however, such judgments and undertakings cannot reasonably be called conservative.

But more is at stake than naming and classifying. Ellmers overlooks that so sweeping a repudiation of contemporary America and such grand dreams of restoration blur, and contribute to the destruction of, the nation's precious heritage—that is, to borrow Jaffa's words, "the moral unity that underlies the moral diversity." Even amid today's acrimony and vituperation, the simple but defining belief in the freedom and equality of all human beings can still be observed in the opinions and conduct—however misguided their policy preferences—of many on the left as well as the right. This abiding conviction should serve as the foundation for rededication to the task of conserving a nation "conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal."

In March 1865, with victory in sight in the final stretch of a terrible civil war, Lincoln summoned Americans "with malice toward none, with charity for all" to "strive on" and "bind up the nation's wounds." If in the course of a calamity of such magnitude and duration rooted in a grievous conflict over whether one human being may own another, Lincoln could discern an underlying moral unity among "Fellow-Countrymen," then it is incumbent upon us to counter teachings and calls to action that espouse malice toward many and charity for some.

Contrary to the most famous lines that he penned and the orneriness and arrogance he frequently exhibited, Jaffa's seminal writings on Lincoln's thinking and statesmanship provide good reason to conclude that the vice of extremism imperils liberty and that the virtue of moderation is essential to the pursuit of justice.

The Soul of Politics: Harry V. Jaffa and the Fight for America

by Glenn Ellmers

Encounter, 416 pp., $31.99

Peter Berkowitz is the Tad and Dianne Taube senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University. From 2019 to 2021, he served as director of the Policy Planning Staff at the U.S. State Department. His writings are posted at PeterBerkowitz.com and he can be followed on Twitter @BerkowitzPeter.