The woman behind the controversial 1619 Project has no business working as a tenured university professor, historians and political scientists told the Washington Free Beacon—and they scoffed at a lawsuit the journalist is reportedly preparing to litigate the University of North Carolina’s decision to deny her tenure.

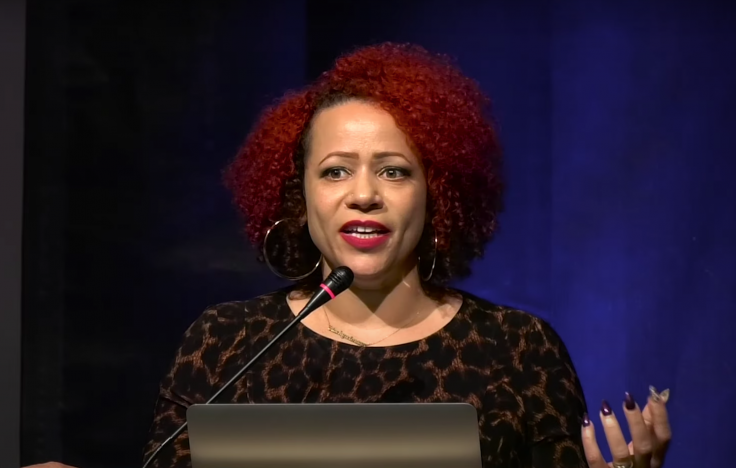

Nikole Hannah-Jones, the New York Times journalist who emerged from obscurity to become one of the most prominent voices in media, is gearing up to sue the University of North Carolina for racial discrimination after the school denied her tenure in May.

While the move was met with outrage in many corners, a handful of academics are pushing back and applauding the school for defending scholarship over popular politics. They include the Yale University political science professor Steven Smith, who said the offer of tenure to Jones was "a gross violation of academic commitments to truth and accuracy."

Lifetime appointments for individuals without Ph.D.s, such as Hannah-Jones, generally require "extraordinary" work, said Michigan State political philosophy professor William Allen.

"Hannah-Jones does not seem to fit the mold of such high academic achievement," Allen said. "As a consequence, the action by the UNC Board seems entirely in keeping with the usual academic practices—the appointment having been infelicitously pushed forward on political rather than solid academic grounds."

The Pulitzer Prize-winning 1619 Project came under fire from conservatives and Marxists alike, with historians dismissing the central premise of Hannah-Jones's work—that the American Revolution was waged primarily to protect slavery—as erroneous.

Hannah-Jones, who refers to herself on Twitter as a "Slanderous & nasty-minded mulattress," has mostly dismissed her critics on racial grounds and suggested white academics feel threatened by her. The University of North Carolina, which is in negotiations with Hannah-Jones and her attorneys, amended its offer of tenure to a five-year position after backlash from donors.

Academics who spoke with the Free Beacon were troubled by Hannah-Jones’s belligerence when responding to critics and argued her conduct is incompatible with the kind of values the university should promote. Lucas Morel, a professor of politics at Washington and Lee University, said the politics of any tenure candidate should be irrelevant. But Hannah-Jones's error-riddled work, such as her insistence that 1619 marked the year when slaves first arrived at the continent despite contrary evidence, make her an unusual candidate for tenure, Morel said.

"What would trouble me about [Hannah-Jones] as a potential professor is not a difference of opinion regarding the relative merits of iconic figures in American history (e.g., Thomas Jefferson or Abraham Lincoln) but rather her unwillingness to address her detractors earnestly and to correct errors of fact and interpretation that have been pointed out by scholars across the political spectrum," Morel said.

Hannah-Jones, who did not respond to the Free Beacon’s request for comment, has enlisted the aid of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund. Her attorneys have alleged the school "unlawfully discriminated against Ms. Hannah-Jones based on the content of her journalism and scholarship and because of her race."

The NAACP did not respond to a request for comment.

Specialists in the history of American slavery, such as Dolores Janiewski of Victoria University of Wellington, called Hannah-Jones "privileged" for receiving a teaching position, particularly given her lack of academic credentials. Janiewski offered several central critiques of Hannah-Jones’s theory of the American founding, including her failure to include the experience of Indians who lived on the continent before European settlers arrived.

"Slavery, while certainly an important part of what became the United States and Mexico, is not the only significant relationship that could be conceived in racial terms nor was the American Revolution only about protecting slavery," Janiewski said. "In fact, the key phrase in the Declaration of Independence led to the end of slavery in Massachusetts in 1783 and its gradual abolition in Pennsylvania and elsewhere beginning in 1780. All of these elements would cause me to want to probe more deeply into questions about whether Hannah-Jones is careful in her interpretation of evidence crucial to the journalistic endeavor."

Some suggested that Hannah-Jones’s appointment at the university’s journalism school raises questions about the quality of education. Despite her title as a "domestic correspondent" for the New York Times Magazine, Hannah-Jones has written only five pieces under her byline since 2018 and has not published a single story since June 24, 2020.

"I don't see any evidence she has mastered [journalism]," said Carol Swain, professor emerita of political science and law at Vanderbilt University.

When interacting with other journalists, Hannah-Jones displays little regard for industry ethics. When the Free Beacon attempted to reach Hannah-Jones for comment in February, she tweeted out the reporter’s personal contact information—a violation of the platform’s rules against doxxing. She later deleted the entirety of her Twitter feed and claimed the ordeal was an accident. The Times is standing by its writer.

"Nikole’s journalism, whether she’s writing about school segregation or American history, has always been bold, unflinching and dedicated to telling uncomfortable truths that some people just don’t want to hear," New York Times Magazine editor in chief Jake Silverstein told the Free Beacon in a statement. "It doesn’t always make her popular, but it’s part of why hers is a necessary voice."