The drama that unfolded at the Atlantic Council last week as nearly two dozen scholars wrote to dissociate themselves from the work of their colleagues is likely to be the opening skirmish in a broader war over the funding for American foreign policy research playing out in academia and in some of Washington, D.C.'s most influential think tanks.

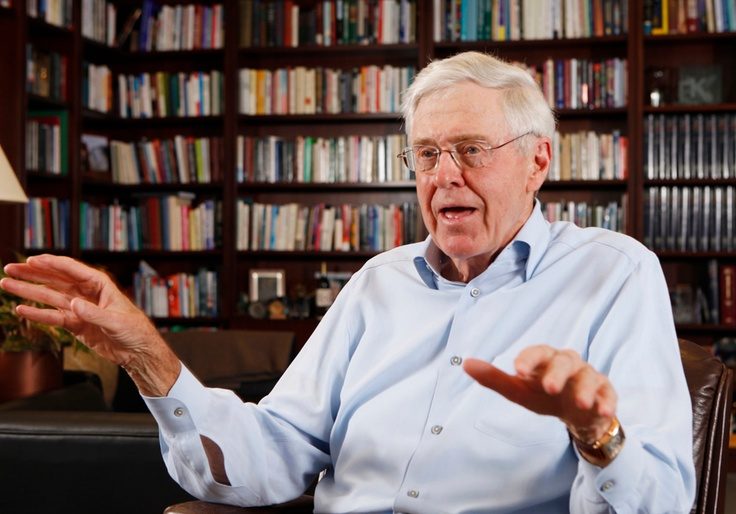

The source of the drama was an analysis published earlier this month by Emma Ashford and Mathew Burrows, who argued that putting human rights at the center of the U.S.-Russia relationship undermines American interests. The piece was published under the aegis of a new national security strategy center funded by the Charles Koch Institute, which has advocated for an isolationist foreign policy—or, as the Kochs and the scholars they fund are now terming it, "a grand strategy of restraint"—with a long tradition in Republican politics from the America First Committee of the 1940s to the Buchananites of the 1980s and '90s.

Intellectual disagreement is standard fare in both worlds. What happened at the Atlantic Council, as more than two dozen scholars issued a terse note dissociating themselves from the work of their colleagues, points to a much deeper conflict. A Politico report published Thursday offered a window into the brouhaha, with several Atlantic Council fellows alleging that the Koch money was corrupting the scholarship or, as one anonymous expert put it: "The Koch industry operates as a Trojan horse operation trying to destroy good institutions and they have pretty much the same views as the Russians."

Simmering beneath the surface, according to interviews with a dozen experts across a half-dozen D.C. think tanks, including the Atlantic Council, is a debate that has roiled American think tanks over the past decade: how these institutions are funded and what, exactly, the donors who underwrite them are getting for their money.

The controversial view that caused last week's kerfuffle—that the United States should look the other way on the human rights violations of its adversaries—is espoused by the scholars who sit atop virtually every Koch-funded program, the result of an aggressive and explicit push to undermine what remains of the country's foreign policy consensus and replace it with a different one.

Over the past several years, Charles Koch Institute vice president William Ruger, President Donald Trump's failed nominee to be ambassador to Afghanistan, has approached virtually every major think tank in the city offering to fund proponents of "restraint," according to a dozen think-tank sources familiar with the situation.

One think-tank expert on the receiving end of a Koch pitch described it this way: "They said to us, 'The debate is not diverse, the restrainers are not respected, and ... our wisdom is ignored.'"

Ruger did not respond to a request for comment, though he himself has written—in an essay in the Koch-funded National Interest—to endorse "restraint," arguing, "Any such perestroika, or new thinking, will be resisted among our regnant elites."

Organizations from the Atlantic Council to the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, the International Crisis Group, the Center for the National Interest, and the Eurasia Group Foundation have taken Ruger and the Charles Koch Institute up on the offer. The list goes on: the Cato Institute, the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, and, as of last year, even the government-funded RAND Corporation.

That explains why a recent RAND Corporation report, titled "Implementing Restraint," stipulates that "advocates of restraint believe that the United States should adopt a less confrontational policy toward Russia," including "accepting a Russian sphere of influence." The report continues: "Advocates of restraint do not argue that Russia poses a significant threat to vital U.S. interests," nor do they believe that Russian disinformation represents "a serious threat to U.S. interests."

A $1.19 million Koch grant is also behind polling from the Eurasia Group Foundation that purportedly demonstrates the American public's support for this approach. "When confronting human rights abuses, consistently across party affiliations, restraint was the first choice, U.N. leadership was the second choice, and American intervention was the last choice," the report found, concluding that "the public desire for a more restrained U.S. foreign policy is significant and diverse."

And that funding helps to explain why Center for the National Interest president and CEO Dimitri K. Simes argues that through a "restrained" foreign policy, the United States should allow Russia and other human rights abusers to "live more or less according to their own standards."

These views caused controversy at the Atlantic Council in particular in part because the organization was founded in the early 1960s to support transatlantic cooperation, and several scholars argued privately that the isolationist views espoused by Ashford and Burrows undermine that ethos with what one fellow described as "red pill pieces."

"That isn't 'realism,' it's cold indifference to freedom masquerading as realism," said Elliott Abrams, the former assistant secretary of state for human rights and humanitarian affairs. "It is particularly disgusting to see Alexei Navalny attacked—at exactly the moment when anyone interested in human rights should be protesting the kangaroo court conviction that has sent him to a labor camp for years."

A handful of D.C. think tanks, including the Center for Strategic and International Studies, have turned down the Koch money, pointing privately to the Kochs' insistence on approving the scholars who would be hired with the funds. "They clearly dictate who you take, there's no doubt about it, in a much more intrusive way than other donors who fund fellowships and chairs," said a source familiar with the CSIS negotiations.

A spokesman for CSIS, Andrew Schwartz, told the Washington Free Beacon that the organization has "on occasion performed some small project work that has been funded by Koch" and that while Ruger did approach the think tank about a subsequent project, "We never got far enough in the conversation to discuss anything about hiring."

A spokesman for the Atlantic Council, Alex Kisling, said that the Atlantic Council’s Burrows approached the Charles Koch Institute about funding and that the Atlantic Council "has full hiring independence."