A financial transaction tax, though popular with 2020 Democrats, would raise little revenue and substantially shrink the U.S. economy, a recently released report concludes.

A transaction tax takes a percentage from financial trades, such as the sale or purchase of stocks, bonds, or derivatives. The United States levies an extremely small charge on each transaction to fund the Securities and Exchange Commission. A number of Democrats would like to bring a full-fledged financial transaction tax (FTT) back for the first time since 1965.

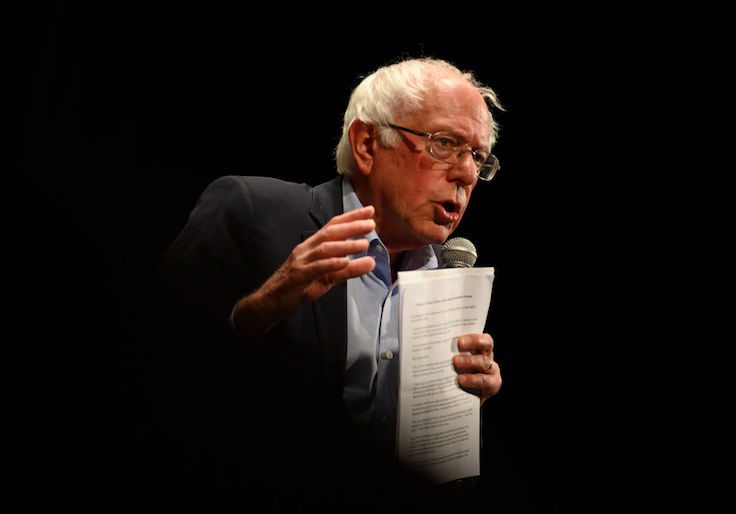

The idea's most vocal proponent is presidential contender Sen. Bernie Sanders (I., Vt.) who has introduced a plan to charge a 0.5 percent fee on financial transactions. Sanders has made the tax "on Wall Street" a central revenue source to pay for his exorbitant spending proposals.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D., Mass.) introduced her own FTT proposal in 2015, Sen. Kamala Harris (D., Calif.) wants one to pay for expanding Medicare, and Mayor Pete Buttigieg has also said that he is "interested in" implementing an FTT. Congressional Democrats have supported the idea outside of the campaign trail. Sen. Brian Schatz (D., Hawaii) has his own 0.1 percent proposed FTT — the bill has more than 200 co-sponsors in the House, including Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D., N.Y.).

These Democrats and others cite several justifications for an FTT. The tax is aimed at "Wall Street," a preferred target of populist liberals—at least in principle, that means it also falls more heavily on those who hold a lot of wealth in investments. Additionally, such a tax would impose major restrictions on so-called high-frequency trading, which involves computer-run trades at fractions of a penny—profits that could be wiped out by the tax.

"This Wall Street speculation fee, also known as a financial transaction tax, will raise substantial revenue from wealthy investors that can be used to make public colleges and universities tuition free and substantially reduce student debt," a brief from Sanders's office reads. "It will also reduce speculation and high-frequency trading that is destabilizing financial markets. During the financial crisis, Wall Street received the largest taxpayer bailout in the history of the world. Now it is Wall Street's turn to rebuild the disappearing middle class."

The scope of the tax, however, would extend beyond the confines of Manhattan, according to a report from the Center for Capital Market Competitiveness, an affiliate of the Chamber of Commerce. The report argues that FTTs shrink the economy and hurt every-day Americans, not just Wall Street fat cats.

"Main Street will pay for the tax, not Wall Street," the report argues. "The real burden [of an FTT] will be on ordinary investors, such as retirees, pension holders, and those saving for college."

Much like a sales tax, the costs of a financial transaction tax would be passed on to consumers, who would pay more for each trade. Taxing transactions does not just drive up costs for the ultra-wealthy, but the 6 in 10 American households that own some kind of investment. Increased costs would have substantial effects on American savings. Under the Sanders plan, for example, the report estimates that a typical retirement investor will end up losing about $20,000 on average from his IRA.

These direct effects are arguably less significant than the overall effect that an FTT would have on the financial side of the economy. As multiple Democrats have acknowledged, the goal of an FTT would be to crack down on complicated financial instruments, such as high-frequency trades, to reduce what they perceive as dangerous market instability.

These instruments mostly serve vital functions greasing the wheels of the economy, according to the center's report. An FTT would erase the razor-thin margins on which market makers operate, and severely constrain other forms of arbitrage. They would also reduce the use of vital risk-management tools, like many derivatives and futures contracts.

An FTT, the report argues, would thus serve to substantially slow the economy. Trade volume would fall; consumer good prices would rise; municipal bonds would generate less revenue for infrastructure; the cost of credit would increase, making mortgages more expensive—in turn exacerbating the homelessness crisis, depressing young home-ownership, and reducing family formation.

Obviously, each of these effects may not be massive—the U.S. economy grew substantially even during the 50-year period when we had an FTT. But, the new report argues, the experience of other nations indicates that the costs to the economy would substantially outweigh any benefit.

For example, they cite an economic analysis of a proposed 0.1 percent transaction tax in the EU—the authors found that "such a tax would lower GDP by 1.76 percent while raising revenue of only 0.08% percent of GDP." Sweden's 1 percent FTT caused a 5.3 percent drop in the Swedish market—meaning a 0.5 percent FTT, as Sanders proposes, would analogously cut nearly $800 billion from U.S. market capitalization. The evidence runs the other way, too: In the year following the repeal of the U.S. transaction tax, New York Stock Exchange trade volume increased by 33 percent.

All of this is why many countries—including Spain, the Netherlands, Germany, Sweden, Norway, Portugal, Italy, Denmark, Japan, Austria, and France—have eliminated such transaction taxes.

"Bad ideas have a habit of coming around again. The U.S., like many other nations, experimented with an FTT and wisely got rid of it. Yet each generation seems to be tempted by the false promise of a painless revenue stream," the report said. "It would be wise to pay attention to the wisdom of experience and again avoid this false temptation. After all, those who fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it."