Children who attend schools overseen by the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ Bureau of Indian Education (BIE) go without hot water for months, sit in moldy classrooms, and have cafeterias with "electrocution hazards," all at a cost of roughly $20,000 per pupil.

Melissa Emrey-Arras, the director of Education, Workforce, and Income Security at the Government Accountability Office (GAO), testified on Wednesday before the House Subcommittee on Early Childhood, Elementary, and Secondary Education, detailing the alarming conditions of schools on Indian reservations.

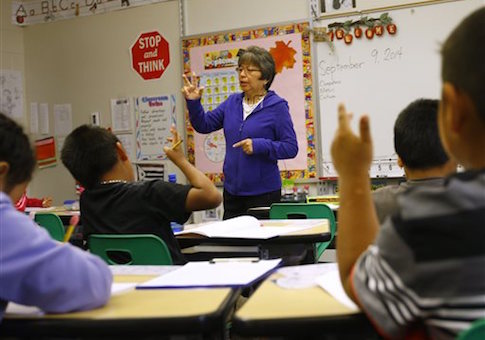

Although the BIE is only responsible for 41,000 students in 185 schools on Indian reservations throughout the country, the agency has been unable to effectively staff, manage, or repair schools. The GAO warned that poor management is harming the education of students on Indian Reservations, who suffer from low test scores and graduation rates.

In one example, Indian Affairs spent $3.5 million on new roofs for one school in 2010, which began leaking shortly after their installation.

"The new roofs already leak, causing mold and ceiling damage, and Indian Affairs has not yet adequately addressed the problems, resulting in continued leaks and damage to the structure," Emrey-Arras said.

"These leaks have led to mold in some classrooms and numerous ceiling tiles having to be removed throughout the school," she said.

A senior official told the GAO in 2011 that the school’s conditions were "unacceptable," though new repairs have failed to fix the problem.

As of late last year, "leaks and damage to the structure continue."

"[Officials] also said that they were not sure what further steps, if any, Indian Affairs would take to resolve the leaks or hold the contractors or suppliers accountable, such as filing legal claims against the contractor or supplier if appropriate," Emrey-Arras said.

Emrey-Arras’s testimony noted that 40 percent of the agency’s architect and engineer positions are vacant, causing numerous construction problems.

For example, one BIE-operated school installed a "high voltage electric panel" next to a dishwasher in the cafeteria kitchen, posing a "potential electrocution hazard."

Another school was left without hot water for nearly a year.

"At one school we visited, a BIE school facility manager submitted a request in February 2014 to replace a water heater so that students and staff would have hot water in the elementary school," Emrey-Arras said. "However, the school did not designate this repair as an emergency. Therefore, BIA facility officials told us that they were not aware of this request until we brought it to their attention during our site visit in December 2014."

"Even after we did so, it took BIE and BIA officials over a month to approve the purchase of a new water heater, which cost about $7,500," she said. "As a result, students and staff at the elementary school went without hot water for about a year."

A $1.5 million bus maintenance and storage facility for a South Dakota school was not long enough to fit larger school buses and has draining and heating problems.

The agency did attempt to save money by firing an experienced speech therapist on contract for a cheaper one. However, the new therapist lived in the wrong state.

"[B]ecause the new therapist was located in a different state and could not travel to the school, the school was unable to fully implement students’ individualized education programs in the timeframe required by the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act," Emrey-Arras said.

The agency also spent $13.8 million on "unallowable spending" in 2014, and one school kept millions of federal funds illegally in an offshore bank account.

"[A]n annual audit found that a school lost about $1.2 million in federal funds that were illegally transferred to an offshore bank account," Emerey-Arras said.

The agency blamed the incident on "cybercrimes committed by computer hackers and/or other causes." The school also had "at least another $6 million in federal funds in a U.S. bank account."

The Indian Affairs education budget for fiscal year 2014 was $830 million, costing taxpayers approximately $20,243.90 per student, double the national average of public schools who spend $10,608 per pupil, according to 2012 data.

Despite the high costs, "student performance at BIE schools had been consistently below Indian students in public schools," according to the GAO. "High school graduation rates for BIE schools were also lower than the national average."

"In conclusion, Indian Affairs has been hampered by systemic management challenges related to BIE’s programs and operations that undermine its mission to provide Indian students with quality education opportunities and safe environments that are conducive to learning," Emrey-Arras said. "In light of these management challenges, we have recommended several improvements to Indian Affairs on its management of BIE schools."

"While Indian Affairs has generally agreed with these recommendations and reported taking some steps to address them, it has not yet fully implemented them," she said.