The idea of visual spectacle, of a genuine wow-factor that will impress a museumgoer in the year 2014, is not something one would commonly associate with an exhibit devoted to the work of 16th Century tapestry-maker Pieter Coecke van Aelst. Indeed, every element here—especially the bit about tapestries—seems to indicate the sort of exhibition that you might visit because you find yourself with an awkward handful of free minutes, and not because you expect to see anything particularly inspiring.

Which was precisely my situation. Unlike the Scottish lord that Harrison Ford impersonates in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, I did not go to view the tapestries—I was at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York to report back to my editors about an exhibit focused on artifacts from the time of Homer and the Bible. After spending a few hours there, and looking to kill some time before an appointment, I wandered into the Pieter Coecke exhibit.

Coecke, who was born in northern Europe at the peak of the High Renaissance and died somewhat young, exhibited the mind-bogglingly diverse set of skills characteristic of the great artists of his age: he was a painter, an architecture enthusiast, a linguist and editor—he translated parts of Serlio’s treatise on architecture into Flemish, French, and German—a maker of woodcuts and prints and stained glass, and more.

The first long room of the Met’s exhibit pays tribute to these diverse contributions. There is also some interesting discussion of the process of tapestry-making, the enterprise for which Coecke is most famous, and which is an involved, elaborate, and collaborative process in which the lead artist works much as a Hollywood production designer, imagining and coordinating the work of others. At the end of this first room a few of Coecke’s tapestries, from a nine-part cycle on the life of Saint Paul, are displayed.

And then one turns a corner to encounter an extremely long, dark second room with a high ceiling, displaying in intermittent pools of light over a dozen of Coecke’s typically 10-15 by 20-25 foot works of woven art, receding into the distance from the viewer’s spot at the threshold.

Stunned by the spectacle into slowing down and taking some more time, it becomes clear that, despite the number of interesting objects next door in the archaeology exhibit, the Pieter Coecke effort was much more thoughtfully organized. Of course, the archaeology exhibit was trying to pay tribute to the better part of the entire Iron Age in most of the Mediterranean world, while the Coecke exhibit was devoted to reviving interest in the work of a single man—but perhaps there is a lesson here about just how much can be done well in a small space, even by the talented curators at the Met.

In part because he died just as his powers were reaching their peak, and in part because his best efforts were expended in the production of tapestries, Coecke’s career hasn’t received the attention that, on the evidence of the exhibit, it deserves. Considered just as a painter, he was clearly the peer of the more famous northern Renaissance artists.

But painting was just one element of a fascinating life and career. Coecke designed sets of tapestries intended for purchase by royal clients like Henry VIII in England, the Hapsburg Charles V, and Mary of Hungary, the latter two of whom gave Coecke official positions in their courts. Ambitious to grow the business, he traveled on behalf of his investors to Constantinople in 1533 to try to expand the market into the court of Suleiman the Magnificent. This didn’t work out—according to Coecke’s 17th century biographer, "Mohammedan Law" and its prohibition on human images apparently sunk the deal—but Coecke, "as he could not be idle," turned his energy to the creation of a woodcut frieze, fourteen feet in length, depicting the 'Customs and Fashions of the Turks,' on display in this exhibit.

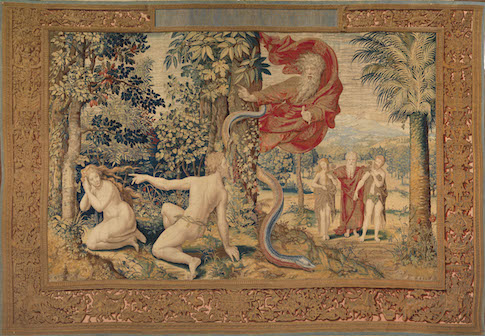

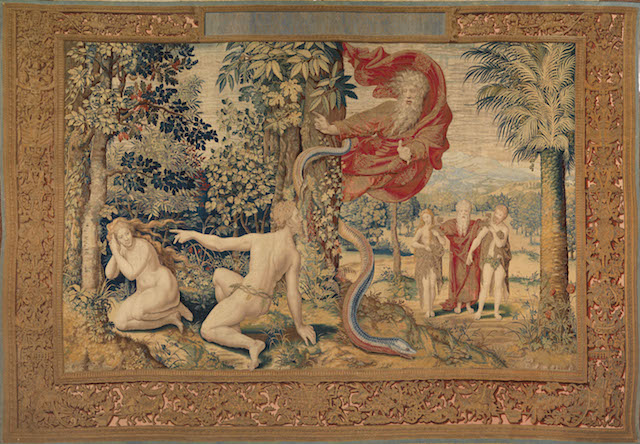

Grandiosity and scale appear to have been the fashions of the day, at least among Coecke’s royal patrons. In addition to the nine-episode Life of Saint Paul, Coeckle produced numerous editions of an allegorical series on the Seven Deadly Sins—bought by, among others, Henry VIII, who no doubt viewed the exercise with a sense of irony—a series about the creation of the earth and the drama in the Garden, as well as sequences devoted to the Biblical lives of Abraham, Joshua, not to mention a life of Julius Caesar and a sequence inspired by Ovid.

Each individual tapestry could take up to a year to weave, and the final result could clearly stand for different things for different patrons. In the fever of Reformation and Counter-Reformation, both the Catholic Francis I of France and the Protestant Henry VIII bought editions of the Life of Paul. For the Protestant north, Paul offered an alternative founding, a theological separation from Peter’s Roman church. For Catholic monarchs, to display a life of Paul in the 16th century was to imply that the Protestants were useless innovators, and that the vision of Christianity they promoted was already encompassed by the existing institution of the church, which took Paul quite seriously.

Similar ambiguity can be detected in the sequence depicting the 'Seven Deadly Sins,' which seem sufficiently pat in their allegorical narratives to be read as straightforward condemnations of their subjects—but also seem sufficiently leering in their style to be read by others as an unsubtle celebration of gluttony, lust, and the rest.

It is certainly with a view to this latter sense that, in the 20th Century, Anthony Powell had the principle characters of the sixth volume of A Dance to the Music of Time, collected at a dinner party at Stourwater—an English castle graced by a tapestry series just like Coecke’s—pose for seven drunken photographs, each replicating the tableau of a different sin, and all symbolizing in the aggregate the flippant viciousness of the interwar years. One of the characters has a nervous breakdown as a result of the exercise.

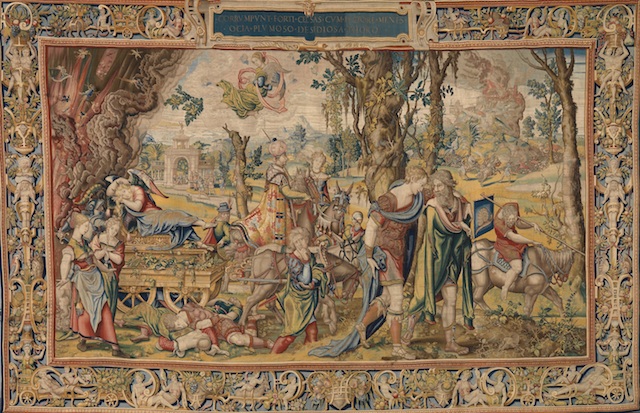

In Coecke's 'Sloth,' a procession led by the personification of Sleep—on the right, carrying a banner depicting a snail, and looking about to fall of his beast—Lady Sloth dozes on her carriage, surrounded by various representations of dissolution.

In the background on the right, Nineveh disconcertingly burns to the ground, having had the ill fortune (in myth, anyway) to be ruled by the lazy and pleasure-addicted Sardanapalus. The exhibition catalogue plausibly suggests that the two figures in the right foreground represent Aristotle—who mentions Sardanapalus in the Nichomachean Ethics—cautioning the young Alexander not to make the same mistakes, but to pursue a life of virtue instead.

Coecke's tombstone, which he had need of at the age of only 48, was inscribed with the tag, "Virtue triumphs over Death." Death nonetheless triumphed over Coecke's reputation for some centuries. The Met's curators have mounted a remarkable counter-offensive.