Seldom have I come across such an arresting first paragraph as that which leads Eric Shanes' new biography of J.M.W. Turner. It seems only right to cede the floor to him:

He lived to paint. Nothing else mattered. For over sixty years he rose at dawn and painted with enormous energy until sunset. Everything was sacrificed to painting, sometimes brutally so. When he became a member of an institution that was largely dedicated to the art of painting, he obsessed about the well being of that body to the same degree. Things were only of any importance if they assisted his painting. Even his favorite pastime served that end, inasmuch as he often used fishing to intensify his understanding of water, and therefore to improve his paining. Money served painting, human relationships and sex too. For Turner, life was wholly subordinate to art. We need to be aware of this from the very beginning. In what follows it is useless looking for much of a life beyond painting, for it barely existed.

Turner achieved widespread fame and financial success in his own lifetime, and his reputation has maintained a tenuous foothold in popular culture even in recent years. There was 2014’s marvelous Mr. Turner, directed by Mike Leigh and starring Timothy Spall—though it’s likely fewer people saw this than saw Darryl Hannah express a desire for "a Turner" (along with a "perfect" canary diamond, a Lear jet, and world peace) in Oliver Stone’s Wall Street.

In Britain he is generally regarded as that island’s greatest homegrown artist. The country’s most prestigious prize for art is named for him and the museum dedicated to British art has an entire wing devoted to his work.

In Shanes' book, Turner gets the first volume of the kind of treatment for which the word "monumental" is reserved. This is a biography of record. Its level of detail, physical heft, and significant price (surely due mostly to Shanes' uncompromising and welcome approach to illustrations) will largely restrict its audience to specialists or the pathologically curious, but that takes nothing from the accomplishment. Nevertheless, non-experts are advised to stick with this print edition—Shanes explains that it merely "condenses a biography more than twice its length [!] that is to appear electronically."

A treatment of Turner’s youth is no study in juvenilia. Son of a barber and wigmaker, he was creating watercolors at age 12 that easily could be mistaken for the work of a college-aged art student today. Accepted as a student at the Royal Academy, he was teaching private lessons himself by 18. At 19, his work was receiving favorable coverage in the London press. At 22 it was being hung in the main room of the Royal Academy of Art’s annual exhibition. At 24 he was elected an associate member there. At 25 he painted ‘Dutch Boats in a Gale,’ which was widely considered to revolutionize the very genre of the seascape, and which earned him election as a full member of the Academy at age 26—the youngest member admitted. Ever.

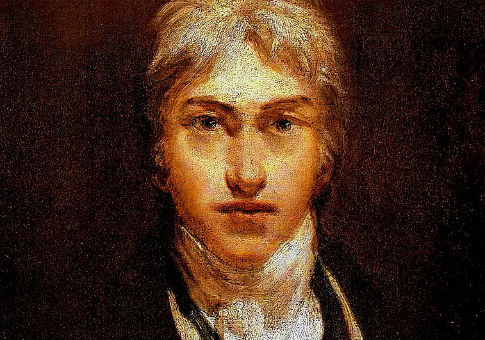

Who was this phenomenon of industry and raw talent, possessed not only of genius but, as Shanes puts it, the "rare capacity to manage that gift"? The casting of Spall (Harry Potter’s Peter Pettigrew, or Wormtail) in the recent film may give you the sense of surprise that many of Turner's admirers felt upon meeting him. He was short, ungraceful, impatient, awkwardly willful, and ungifted with words. Thomas Cole, who idolized Turner, remarked, "I can scarcely reconcile my mind to the idea that he painted those grand pictures. The exterior so belies its inhabitant the soul." His students found him eccentric, and his lectures on perspective at the Academy were a disaster. Competitive with his peers to the point where he often seemed to be engaged in petty one-upmanship, he made many enemies.

He was an intensely private man, and he had much to be private about. His mother had gone mad, and through intermediaries he and his father had her committed to a series of mental hospitals. She died in one of them and was buried in a pauper’s grave unattended by any member of her family. In his youth he had a common law wife whose existence he kept a secret, in part for financial reasons—she had a pension that would disappear if they married or were discovered to be engaged in immorality. He also kept secret the existence of their two children, and did his best to be lightened of his responsibilities for them after his relationship with their mother ended.

As a young artist he had no living, literal master. Thomas Malton the Younger walked him through the technical intricacies of perspective, but Turner surpassed Malton's abilities while still a teenager. His true masters were the Masters: Rembrandt, and later Claude and Poussin. In a famous, if possibly apocryphal, tale, he was reported to have burst into tears as a youth upon studying Claude’s ‘Seaport with the Embarkation of Saint Ursula,’ "because I shall never be able to paint anything like that picture."

In a sense, Turner’s life was a competition with Claude and others of that rank, and it is not absurd to argue that he came out on top. Brilliant and sensitive, with an appetite for literature and a hugely powerful memory, it was as if his lack of verbal ability was somehow related to his complex and profound visual genius. Influenced by the conventions of history painting and by Joshua Reynolds’ belief that great art is possessed of "grandeur," Turner saw his painting as commentary—sometimes social, sometimes metaphysical. A great painting, by definition, had dimensions of allegorical or otherwise moral significance.

In these beliefs Turner was no revolutionary. But he was unusual in his relentless, habitual demotion of the human figure in history painting, preferring to emphasize the power of nature. Among Shanes' more interesting work are the mini-essays on such issues that add salt and pepper to the book’s otherwise strictly chronological approach. Of course Turner knew how to depict human figures—drawings from his time at the Royal Academy schools demonstrate this beyond any doubt. His slapdash treatments were a decision. And it is silly, Shanes implies, to see Turner’s work as some mere function of the fashion of his day for the picturesque. To the extent that Turner painted ramshackle buildings next to grand cathedrals and misty countryside and the like, these subjects were a function of his own authentic and ambivalent response to modernity.

Shanes chooses as his stopping point Turner’s triumph in 1815 with ‘Dido Building Carthage,’ which he considered to be his chef d’oeuvre. I look forward to Shanes' next installment, as still to come are further decades of celebrity, prodigious output, a lifelong commitment to the health of the Royal Academy, Turner’s charity to young artists, his radical experimentation with form and clarity—a kind of proto-Impressionism—and more private shame.

Turner never married—an unsurprising decision from a man who remarked, "I hate married men; they never make any sacrifice to the Arts, but are always thinking of their duty to their wives and families, or some rubbish of that sort." All his vast ambition and devotion went into painting. Today, ‘Dido Building Carthage’ hangs in London’s National Gallery in a room with Turner’s ‘Sun Rising Through Vapor' and two Claudes: ‘The Mill’ and ‘Seaport with the Embarkation of the Queen of Sheba.’ Turner bequeathed the paintings to the nation only on condition that they would be hung in this company. It is unclear whether we are meant to linger in the gallery and consider the two masters peers—or to look and conclude that Turner won.