The Western novel was last seen riding off in a slow lope, out across the prairie under the big sky. We watched him as he moved through the purple sage: a big man dwindling in the distance, lonesome as a dove. How much did we really know about him? Born a Virginian, folks said, he broke with the good old boys after a strange incident he wouldn’t much speak of. Making his way west, he soon proved himself a heller with a gun, truly a man of grit. Still, the story goes, he was a reluctant shootist, always ready to ride away, down through the sea of grass. "Come back," we cried, but he wouldn’t. Or couldn’t. And wasn’t he at once the strongest and yet the weakest of all his outcast kind?

Or, to put the matter a little less metaphorically, the Western novel was once a popular and well-defined form of genre fiction—stacked without embarrassment beside all the mysteries and the science fiction books, the spy tales and the romance bodice-rippers, on bookstore shelves. The popularity of Owen Wister, with The Virginian in 1902, and Zane Grey, with Riders of the Purple Sage in 1912, pulled the Western out of the pulp of the penny dreadfuls and dime novels, defining a genre that would gallop along for decades, with endless outpourings from the likes of A.B. Guthrie, Luke Short, and Max Brand.

But doom was waiting around the corner of the saloon, with a scattergun in its hands. Yes, Louis L’Amour became one of the bestselling authors in the world during the 1960s and 1970s. And yes, from Thomas Berger’s sprawling Little Big Man (1964) and Charles Portis’s tightly constructed True Grit (1968) to Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian and Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove (both 1985), the Western demanded that it be recognized as a means for serious literature. By the 1990s, however, readers had forgotten Westerns so completely that bookstores carried hardly any of the old Louis L’Amour-style of popular titles and even the more ambitious works—from Philip Kimball’s sad Liar’s Moon (1999) to Patrick deWitt’s comic The Sisters Brothers (2011)—came to seem specialty books for the handful of readers with a Western hobby.

Enter the novelist Ron Hansen, riding down from the mountains to the ominous streets of a dusty Western town, strapping on his gun-belt for the first time in over thirty years because—well, because who else is left to fight the old fight over the Western? Born in 1947, a Nebraska native (and now a literature professor in California), Hansen began his literary career as part of the general attempt to upscale Western fiction. His first book, Desperadoes, appeared in 1979 and told the story of the Dalton Gang through the not entirely trustworthy memories of the elderly Emmett Dalton, last survivor of the outlaw band. And he followed it up with his second novel, The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford in 1983, another outlaw’s tale.

Though the books sold well and received glowing reviews, he abandoned Westerns in the years that followed. Catholic themes moved to the forefront with such books as Mariette in Ecstasy (1991) and Exiles (2008). His 1996 Atticus did have a Western setting, but it was at least partly the Parable of the Prodigal Son, retold with a modern ranch family (and it remains, to my mind, his most powerful and moving book).

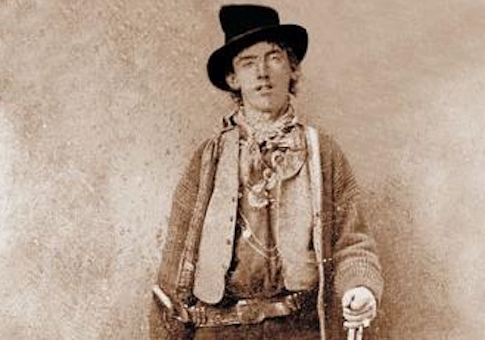

And now we have Hansen’s latest work, The Kid, a new look at Billy the Kid—without much explanation for why the novelist has returned, decades on, to add a third installment to his stories about bad men in the Wild West. Part of the reason is surely Hansen’s long-standing interest in the Western. The comments he’s made about the book suggest that he’s been collecting string on Billy the Kid and the Lincoln County War since he finished The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford—and thus that he always intended to complete his outlaw trilogy.

But even more, I suspect, Hansen was brought back to his old fascinations by the interest in voice he has shone in recent work. "You’ll want to know about his mother, she being crucial to the Kid’s becomings," the book begins. And with those words we are cast immediately back into the world of the Western—not the world of the West, for who can say how people in that thinly populated land actually spoke in the 1870s? But with his opening line Hansen takes us straight into the literary West: a world that begins with language.

Fortunately, Zane Grey’s orotund style in the early Western (think bad Edwardian imitations of Dickens; it wasn’t just the sage that was purple) quickly gave way to the professional genre style practiced in subsequent decades by Max Brand and Louis L’Amour. But a much greater revolution happened in 1968 with Charles Portis’s True Grit, probably the most influential Western ever published. True Grit is driven by the language its characters speak, every one of them an amateur rhetorician, fascinated by the words they pronounce with an untutored formality. "If in four months I could not find Tom Chaney, with a mark on his face like banished Cain, I would not advise others how to do so," as Mattie Ross tells the sheriff Rooster Cogburn.

In The Kid, Hansen keeps as close as he can to the known facts about Billy and the Lincoln County War, but it should be no surprise that he enriches the story with invented dialogue. And though he varies the voices as the different characters speak, he maintains the fascination with diction, in the convention Portis gave the modern Western. "I hardly do nothing with people involved. Railroads and banks, that’s complexicated," as Billy tells Jesse James, refusing the invitation to join James’s gang. "I’m riding opposite of the owl-hoot trail now and not interested in your livelihood."

And the diction-driven prose carries over to the third-person narrator, a kind of reporter who has been captured by his subjects’ voices. So, the killer Jimmy Dolan "had been prosecuted for murder but was acquitted for Wild West reasons." The mix of corrupt politics and violent culture create "a West where judgments of legality go to the highest bidder or at the insistence of a gun."

One of the things Hansen wants to remind us is that Billy was only 21 at the time of his death. When the Lincoln County War broke out in 1878, it was essentially what Hansen calls a "petty grocery store rivalry" between two factions looking to supply the local Army post. But when Billy’s favorite, the Englishman John Tunstall, was killed, Billy begins his campaign of revenge. And he is, as Hansen presents it, more or less in the right. As the fight drags on, Billy ends up the last man left—"It was a collective thing, but only Kid Bonney got accused of the murders"—when the governor failed to follow up on a promised pardon. Captured, Billy escapes, killing two jailors, and it is those deaths that change him from a wild but charming young daredevil to something darker and more doomed.

And then, of course, Pat Garrett, former outlaw turned Lincoln County Sheriff, at last tracks Billy down and kills him in July 1881. The Kid is drier, more aloof, than Hansen’s previous Westerns. It’s also less deep, less rife with symbolic elements than Atticus or Exiles or even The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford. But in its pages, The Kid tells the story of Billy Bonney cleanly and well, sorting through the historical material to give us a picture of a young man—so very young—whose body "acquired its education in dying" when Pat Garrett shot him down.