"The younger generation just doesn't get Edward Gorey," an older woman said. She was dressed in a knitted brown cardigan, leaning on the elbow of her husband. She turned her head and noticed me. "Oh! Except for you of course. You're here!" I was at the exhibit "Gorey's Worlds," a retrospective of the eminent author and illustrator accompanied by his collected art at the Wadsworth Atheneum in snowy, windy Hartford, Conn.

Gorey is immensely popular and badly misunderstood. He was born in Chicago in 1925, where he became a ballet fanatic. After a two-year stint in the Army, his enthusiasm for the arts still intact, Gorey went to the Art Institute of Chicago but left after only one semester to study French at Harvard. When he moved to New York City in 1953 to become an illustrator, he was known to walk the streets in fur coats and canvas Converse before going home to his apartment filled with cats.

When one of his six cats died, he refused to get another. After you get more than five cats, he said, they all adopt the same personality. Gorey never married.

The world "is full of scary things," John Updike once said, "and it is children's-book illustrations that first offer to display them to us." "Gorey's Worlds," curated by Erin Monroe, shows us just that. An eccentric in art and life, Gorey continued the Grimm Brothers' tradition of enticing and terrifying children with whimsical, morbid stories. Like any great children's books, they appeal to adults, who can appreciate the ironic, acerbic wit and strange and intricate illustrations. Upon his death in 2000, Gorey surprised the Atheneum by leaving the museum his created and collected art, for reasons as mysterious as the artist himself.

The odd nature of Gorey is on display throughout the show. I was greeted by one of his fur coats suspended from the ceiling, flung in a still of movement not unlike his illustrations for the Lavender Leotard (1970). The pages of that book, which was commissioned for the 50th anniversary of the New York City Ballet, are hung in chronological order on one lavender wall, along with other pages that didn't make it to the final copy.

The story shows Gorey's ballet obsession using his favorite subjects: children, or "tinies" as he called them. It speaks ironically to insider ballet aficionados, with one tiny saying, "Don't you feel the whole idea of costumes and sets is vulgar?" On another, a small girl tells her male partner, "I think it would be more humorous if they threw you at me."

Gorey bought season tickets for every New York ballet season and never missed a show. One year, he saw every single production of the Nutcracker—all 32 of them. That much Tchaikovsky could possibly drive someone crazy. The exhibit's accompanying music—a loop of the theme music for PBS's Mystery! show that Gorey animated the introduction for—had an equally overwhelming effect.

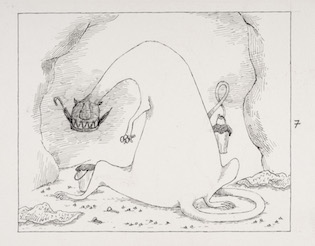

New York: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1963. Pen and ink on paper. © The Edward Gorey Charitable Trust.

At the point in his career when he made the Mystery! introduction, Gorey's work was famous. But his terrifying plots were considered slightly inappropriate by some audiences. In The Evil Garden (1966), a family who hopes to enjoy a public garden is met with nightmarish horrors. The museum hangs the illustrations where a "hissing swarm of hairy bugs / Has got the baby and its rugs." The Atheneum also shows a study Gorey made for The Insect God (1961), where four-year-old Millicent Frastley takes candy from an insect and is swept away to be sacrificed to an insect god.

However strange the plots, the illustrations are complex. They are made up of detailed cross-hatchings and are even charming as they are cryptic, as in the case of The Doubtful Guest (1957). The story follows a penguin-like creature in sneakers who shows up at a Victorian family's home with no explanation and is exceedingly mischievous. I could hear people laughing as they looked over the drawings.

Although he preferred to be called an author, Gorey was an unmatched illustrator. His thin ink lines match the detail of Albrecht Dürer—they fold into textures, create the ripples of water, and cast shadow and light with a deliberate hand. The characters they outline are hauntingly enigmatic, as if they floated as ghosts out of the House of Usher. Gorey, whose life was devoid of romance (by choice), gave all his energy to creativity.

I was disappointed the exhibit lacked illustrations of Gorey's famous Gashlycrumb Tinies (1963), an A-B-C book that depicts the unfortunate fates of 26 children: "A is for Amy who fell down the stairs / B is Basil assaulted by bears…" But this was made up for with the beautiful illustrations for The Turning Fork, drawn in 1966 and published in 1990. Gorey's quirky monsters are a focus of the exhibit, and in this case one befriends a young girl with a disturbing past. That was not so in The Wuggly Ump (1963), where the wuggly ump monster devours children.

While most of his work is impressively small, normally about 7 inches high, the museum shows some of his larger drawings with a cover for the Dec. 21, 1992 New Yorker, which showed a rare use of color, and the original poster for the production of Dracula (1977). It was Dracula that originally brought Gorey his much deserved fame and wealth (he won a Tony for best costume design), and he used his royalties to buy a house in Cape Cod.

He called that house the "elephant house," because of its chipped gray paint and large size—at least large enough to house his collection of 26,000 books and beloved cats.

In this house he moved his collection of art, which makes up at least 50 percent of the exhibit. The pieces reflect Gorey's taste and inspiration, with works by artists who loved animals and the strange as much as he did. There is an ink drawing of a cat by Manet, a print by Munch, a cartoon by Thurber, an ink drawing of a sleeping tiger by Delacroix, two Albert York oil paintings, and much more. Sandpaper drawings from 1850 that hung above Gorey's mantle show spooky black and white landscapes of ruins and an obelisk, a church and graveyard, and Niagara Falls.

One of the most eye-catching pieces in the museum is the "Phantasmagorey" (1974). A play on words of phantasmagoria, or a sequence of images one would see in a dream, six tiny drawings come together to illustrate Gorey's personality. One vignette depicts one of his ghostly femme fatales, another shows bats flying across a moonlit sky. On a pile of books is perched a smiling cat, and next to that is a child clutching a doll. Underneath those is a self portrait, of Gorey in a fur coat with his back turned and feet poised in ballet's fifth position. An urn next to the self portrait reads "Phantasmagorey" across the front.

Despite the elderly woman's comments when I entered the show, Gorey's work should be welcomed by the generation who grew up watching Tim Burton and reading A Series of Unfortunate Events. The work of Gorey himself and those he inspired is unavoidable to people who are thrilled by the strange and the weird. It is through them that Gorey bridges generations and will inevitably do so for ages to come.