Sometime last year I was driving out Route 50 in the direction of the Blue Ridge as my then-fiancée, riding shotgun, fiddled with the Redfin app on her phone. She was investigating the prices of houses in the area, properties we were idly dreaming about buying one day after I chuck in journalism for something more lucrative and socially acceptable, like high-class art theft, or running guns.

This being Virginia horse country, the houses were all absurdly expensive, but one listing, tucked in there as though it were a perfectly natural thing to find on an real estate app used by, you know, normal people, made us question whether there was some sort of error, and then just made us laugh: Rokeby Stables, asking price $70 million. A couple thousand acres, multiple full scale manor homes, plenty of stuff for your horses—and an airport.

A little research jogged my memory: this had been the estate of Paul and "Bunny" Mellon. Mrs. Mellon had died in 2014, after a final few decades not free from tragedy and embarrassment, but which had come at the end of a remarkable life—including marriage to Paul, sportsman, collector, OSS veteran, and son of the Great Man, Andrew Mellon. I note with a somewhat irrational touch of sadness that the property has since been subdivided: at least one chunk can still be yours for the more reasonable sum of $12 million.

Subdivision is the destiny of great fortunes, of course, and while the Mellon name is on the side of any number of prominent buildings and institutions, the family’s place in the public consciousness has been overtaken by subsequent generations of billionaires. But one of the Mellons’ most important contributions to American life doesn’t bear the family name: Washington’s National Gallery of Art, founded by Andrew, and much loved and aided by Paul over the subsequent decades.

A new exhibition at the National Gallery now pays tribute to Paul’s collecting, though of course both he and his father were major buyers and benefactors, if entirely different in their approaches. Andrew—titan of finance, secretary of the treasury in the ‘20s, and object of the retributive anger of New Deal Democrats—approached art collecting the way Napoleon approached Europe. His greatest transaction involved throwing some liquidity in the direction of the Soviet Union in return for 21 of the crown jewels of the Hermitage right at the start of the Great Depression. This, and other deals made on a similarly imperial scale, formed the foundation of the National Gallery’s collection when it opened in 1941.

Andrew didn’t live to see the museum built, dying of cancer in 1937 after several bitter rounds with the IRS, who had pursued him for tax evasion after he left public office. Indeed, some in the Roosevelt administration were leery of the gift of the Gallery, believing it to be a thinly veiled effort at public rehabilitation, not to say inoculation against further legal action. The young Paul, who had a difficult relationship with his father—you can’t be surprised to learn that Andrew wasn’t the warmest of men—was leery too, though for different reasons, writing at one point during the early planning stages that the Gallery was "just one more investment, one more tremendous Mellon Interest, one more prop for the scaffolding which holds up [Andrew’s] gigantic, intensive, mysterious ego."

But after his father’s death Paul saw the gift to the nation through, and far from turning his back on it, spent the rest of his life noblessing the old oblige with great zeal. The current exhibition focuses on smaller works he and his wife bought and donated—watercolors, pastels, and the like—which due to their fragility can only enjoy limited periods of display. Though Paul’s collection was certainly grand—thousands of objects in the end, many of which now reside permanently at the National Gallery—the principle behind its assembly was strikingly different than Andrew’s: more personal, more aesthetic, less strategic, though perhaps similarly unscholarly—the collection of a son of a great fortune, rather than that of he who gathered the capital. As Paul himself put it, in a remark highlighted by the curators:

One of my failings as a collector may be my lack of curiosity about the lives of the artists, their social and political background, and their places in history. I am also little interested in their techniques, their materials, or their methods of working. I sometimes worry about it, but then I say to myself, ‘Why should I have to?’

If I had these beautiful small works by Degas and Homer and Turner on the walls of my home, I guess I wouldn’t worry about much either. Mellon went on, saying that the value of art for him was like that of "poetry for Wordsworth … ‘emotion recollected in tranquility." A dealer friendly with Mellon offered further evidence of this in a tribute penned back in the ‘80s:

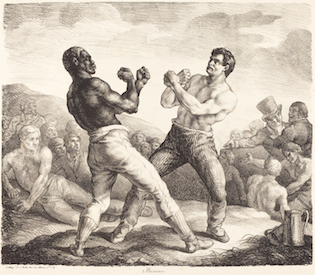

…[T]he subjects in both eighteenth century English and nineteenth century French paintings were often those that he and Mrs. Mellon admired in real life: light falling through the trees and on water, racing clouds, intimate scenes of everyday life, elegantly appointed rooms, a head bent over a book or an embroidery, pretty women, flowers and gardens, and games, sports and animals.

The dealer, Geoffrey Agnew, did detect some technical consistency, noting a taste for "the intimate and the spontaneous, for painterly qualities and freedom of handling," and that is certainly on display in the current exhibition—though, as Agnew notes, the personal trumped any sort of theoretical concerns.

Indeed, there is a strong sense in the current exhibition that the point of this collection was pure pleasure: Turners and Constables because the Mellons loved the English countryside; boxing pictures by Gericault and Bellows because Mellon, a talented rider, loved competition; a lot of it simply because it was beautiful, and they could afford it. One picture in particular arrests as an example of the intimate and the personal: a Homer depicting two children hopping a turnstile at the foot of what could very well be the Blue Ridge, the suggestion of the mountains through the humid air conveyed so casually, yet so convincingly, by a relatively simple zone of green. Maybe it reminded the Mellons of summer in the country around Rokeby—though the appropriate attitude to such questions seems to be summed up by Mrs. Mellon in remarks she gave at the opening of an exhibition of her family’s art at Yale in the ‘70s: "We collected all this. Then they tell us why we collected them…"