In Denmark at the start of the 19th century, a young archaeologist named Christian J. Thomsen was given the intimidating task of organizing a growing horde of ancient objects being stockpiled in preparation for the eventual foundation of a National Museum of Antiquities. As David W. Anthony relates in his splendid The Horse, the Wheel, and Language, Thomsen made the decision to separate and display his collection in three large halls: one for objects made of stone, one for objects made of bronze, and one for those made of iron.

This separation of objects, which had previously been jumbled together both literally and in the human understanding, was all at once both revolutionary and old news. It was old news because classical authors had long speculated about successive "ages" of man that had preceded recorded (or at least well-recorded) history. They quibbled about their number—Hesiod speculated that there were five, and Ovid four—but in general they believed that these ages involved a devolution in the moral condition of man, and that progress had gone from a Golden Age, through Silver to Bronze, and ultimately to the grim period of Iron in which the Greco-Roman authors themselves lived.

Thomsen’s approach echoed this ancient analysis, but with obvious differences, the most important being that his was based on an empirical sorting of material objects. Moreover, his scheme implied not so much man’s moral devolution as his technical evolution: that humans had begun by using stone tools, then had learned the arts of bronze and iron work as their power and sophistication grew. Thus was born what is today the universal scientific understanding of prehistory’s chronology.

Visiting the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s impressively wide-ranging (indeed, from a point of view of narrative focus, almost too wide-ranging) exhibit, "Assyria to Iberia at the Dawn of the Classical Age" one is struck by just how impressive it is that archaeologists today are able to know so much—or, to speculate so plausibly—about these strange, mute objects they have pulled from the ground. At the tail end of a two-century-long (and ongoing) project of collation and investigation, the early history of man has been made to speak out loud, despite the relatively scant amount of literary evidence available to us before the middle of the first millennium B.C.

The Met’s exhibit is a sequel to two earlier shows it hosted, focusing on the Third and Second Millennia B.C., respectively—thus, picking up in the middle of the Neolithic (the latter part of the Stone Age, where pottery and agriculture were in use) and carrying the story through the Bronze Age. The current exhibit brings the visitor through the collapse of the Bronze Age and into the Iron—into the periods commemorated by foundational western texts like Homer’s epics and the earliest books of the Bible.

Homer, scholarly consensus suggests, was an Iron Age poet writing nostalgically for a lost Bronze Age of heroes and palaces that was in his estimation both more noble and wealthier than his own. On the physical evidence available at the Met, there certainly seems to be something to this. Something bad clearly happened to mankind around the turn of the 12th Century B.C.. Mycenaean palace civilization and the Hittite and Egyptian empires more or less simultaneously collapsed, or least substantially contracted. There is evidence of mass sea- and land-borne migrations—in the Holy Land, settlements excavated along the Jordan River seem to show a substantial influx of new inhabitants who did not eat pork arriving around this time.

The earliest objects in the exhibit, which represent a period right before the apparent darkness of the early Iron Age, are intrinsically beautiful and even breathtaking when one considers that they come from the second millennium B.C.. An intricately carved ivory box depicting a bearded archer on a chariot hunting game sprinting ahead of him, or a bronze wheeled stand—essentially a piece of expensive furniture for carrying a vessel of water or wine—with scenes of lions on the attack and grazing animals, both from Cyprus, would be impressive if you thought they came from the peak of the Roman Empire. These objects are well over a thousand years older than that. Equally of interest is that these Cypriot objects seem much more delicate and than many—even most—of the later objects on display. The reason for Homer’s nostalgia, and the classical consensus that mankind was in decline, seem somewhat well-illustrated by the exhibit.

Also on display, in this exhibit as in its two prequels, is the raw diplomatic power of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. By my count, there are artifacts from thirteen different countries’ museums here, counting the Vatican. The horde is so vast, in fact, that one gets the sense that the curators have struggled to construct a coherent account or narrative thread to tie such a sprawling collection together. Something about trade, something about a globalized economy in the Mediterranean, and so on.

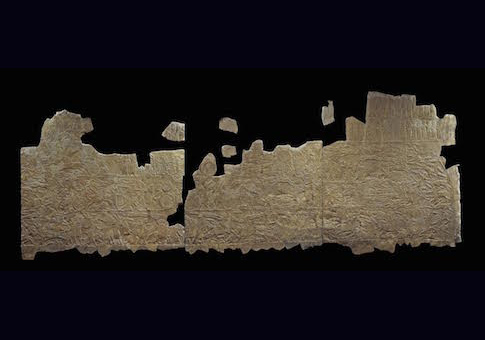

No matter. The objects themselves, not likely to be under the same roof again anytime soon, are what one goes for. Consider the 9th Century Aramaic inscription commemorating the triumphs of Hazael, king of Aram-Damascus, over his enemies: on loan from the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, it includes the only mention of the House of David outside of the Bible.

There is also the show-stopping relief commemorating the victory of the Assyrians over the kingdom of Elam in the battle of Til Tuba, which apparently occurred in the middle of the 7th Century. This enormous object, on loan from the British Museum, depicts the fighting and its brutal aftermath, in which—among other punitive measures—members of the disloyal Gambulu family are forced to dig up their ancestors’ skeletons and grind their bones to dust.

Such specific interpretations can be made because the relief was helpfully inscribed by its sculptors with captions. The fate of the Elamite king, Te-Umman, is made particularly clear due to the fact that his receding hairline makes him easy to pick out as specific character amidst the slaughterhouse ensemble. In the words of the caption:

Te-Umman, king of Elam, who in fierce battle was wounded, Tammaritu, his eldest son, took him by the hand (and) to save (their) lives, they fled. They hid in the midst of the forest. With the help of Ashur and Ishtar, I killed them. Their heads I cut of in front of each other.

As I was working my way through the scenes of the Til Tuba relief—in which the executions of poor old Te-Umman and his son are certainly not only beheadings portrayed—a well-dressed older woman, who seemed to me to have an Egyptian accent, interrupted my examination to point at the scenes of decapitation and remark, "Look! It is the Khalifa!" Laughing, I agreed. Nineveh, where the relief was unearthed, is just across the Tigris from modern day Mosul.

There’s a theme for the exhibit: The more things change…