For just over a decade, Washington’s National Gallery of Art has provided dedicated space on the ground floor of its West Building for the exhibition of photography. This was a significant devotion of resources for a museum that has far too many first-rank objects to display any more than a fraction of them at a time. Consider, for example, that it currently has a Vermeer sitting in storage, when there are thought to be only 30 or so Vermeers on this earth.

The five photography galleries play a swing role, exhibiting pictures drawn from the permanent collection and shows meant to travel: nothing is on the wall for long. This year has seen a series of exhibitions devoted to celebrating the 25th anniversary of the National Gallery’s effort to collect photographs systematically. It came late to this game, compared with other prominent art museums, but has amassed something like 15,000 prints, some of them critical in the history of the art.

The anniversary celebration closes with an exhibit that opened this week devoted to recent gifts. This is an impressive collection of prints, including items from photography’s early days in the 1840s to the digital era. It presents an opportunity to take in a brief history of photography, as compressed into five rooms and conditioned by the tastes of the National Gallery’s benefactors.

What’s striking about the images from the 19th century is how closely they echo the European painting of the day. As a form of art, photography was not yet taken particularly seriously, and its practitioners struggled to determine how best to leverage a medium that, rather than imitating the appearance of light through shading or pigment, actually captured the light itself. Moreover, it captured it with such cumbersome equipment that the photographer might as well have been traveling around with paints and an easel.

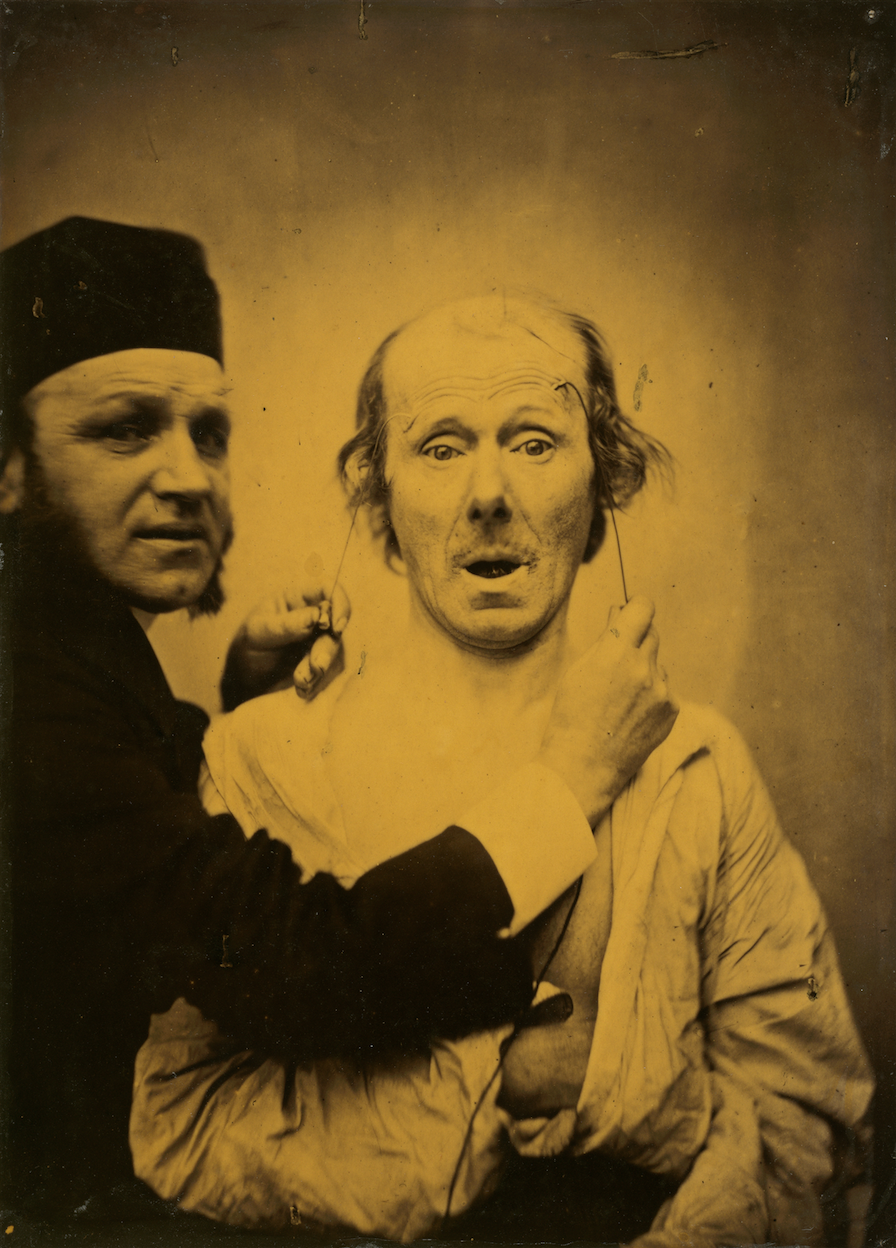

Landscapes, architectural details, portraits, still lifes—these painterly genres dominated early photography, though there must have been a shock of the real for those viewing at Joseph Vigier’s look at a pass in the Pyrenees, or Charles Marville’s eerie, empty streets of Old Paris on the eve of their destruction. There was also, of course, early journalism and documentary photography, including weird forays into pseudoscience—the exhibit’s creepy display of Guillaume-Benjamin-Amant Duchenne’s documentation of his "experiments" with creating facial expressions through electric shocks won’t be easily forgotten.

It wasn’t just the genres of painting that photography was aping, but the broader aesthetic concerns—exotic scenes of the orient, romantic landscapes, and such. The photographs on display from the early 20th century are no different in this respect: as painting became occupied with questions of how best to depict the speed and chaos of a rapidly industrializing West, so photographers like Alfred Stieglitz and László Moholy-Nagy started making pictures that at times look an awful lot like the work of the Italian futurists.

It’s right around this point that painting and photography parted ways, with painters largely retiring from the field of objective representation, having been relieved of the need to perform this task by their vastly more efficient competition, the men and women wielding cameras. Photography—or, to be more specific, the photographs emphasized in this exhibit—took a turn for the political as cameras grew more mobile, and photographers gained the ability to get out on the streets with ease. Dorothea Lange’s image of a strike in San Francisco in the ’30s sets the tone.

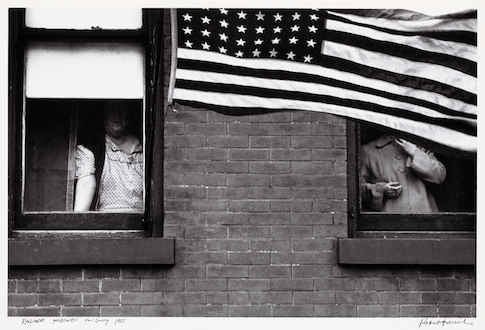

Postwar, the photographs in this exhibit—and perhaps generally in high-concept American photography—get edgy. One of the dominant artists of the period, Robert Frank, looked, in the opinion of the curators, "beneath the surface of American life to reveal a lonely, alienated people bedeviled by racism, ill-served by their politicians, and anesthetized by a rapidly rising consumer culture." America was a sham, Frank and William Klein and Diane Arbus edgily asserted, in agreement with all of their colleagues. Their pictures are often self-consciously grotesque, and the lens seems to get trapped in a multi-decade sneer, mocking the pretensions of the powerful and the common man alike—especially if that common man decided he wanted to live in a tidy, suburban home.

Even Richard Avedon, whom the curators aptly describe as the "consummate insider," composed portraits of the American political elite that were subtly corrosive, showing generals and cabinet secretaries and prominent pols as vulnerable, everyday, entirely life-sized figures. It is not the kindest commentary on the judgment of the members of this elite that they kept showing up for sessions with this 20th-century Goya.

It is a great shame that there isn’t space to display the most important items of this collection on a permanent basis, but then this applies to the entirety of the National Gallery’s holdings. A few years ago a fair amount of attention was given to a congressman’s somewhat quixotic effort to seize the beautiful art-deco federal building across the street from the National Gallery currently occupied by the Federal Trade Commission, and annex it to the museum.

Too bad that hasn’t worked out. The Federal Trade Commission’s work is surely important to the functioning of the republic: Without them, who would shake down the corporations not sufficiently lining the pockets of the dominant factions in American politics? Still, this seems like work that could be performed from anywhere in the capital area, and it would be nice to take the Vermeer and some of these photos out of storage.