In the early 1960s, when Neil Gaiman was eight years old, he read a story called "The City on the Edge of Forever" in the collection Star Trek 2. The piece was an adaptation of a Star Trek teleplay that had been written by one Harlan Ellison. Two years later, Gaiman read a story called "I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream" in the anthology World's Best SF Third Series. This hallucinatory, post-apocalyptic tale of four humans trapped inside a sentient and psychotic computer had such a terrifying effect on Gaiman that he looked up its author. Ellison had written it too.

"I grew up on Ellison," Gaiman wrote in the introduction to Harlan 101 (2013). "I learned so much from reading his stories, so much from reading his essays. Sometimes, I'd disagree with him, but I'd have to think about why I was disagreeing with him, and I suspected that Harlan would be happy, as long as I was thinking."

Who is Harlan Ellison? Novelist, essayist, short-story writer, television critic, anthologist, screenwriter, lecturer, activist, gadfly, he is the author of dozens upon dozens of books, and the winner of numerous awards. You can read a partial list here. Praised by Isaac Asimov ("He is never anywhere without you knowing he is there"), Michael Crichton ("He is a genuine original, one of a kind, difficult to categorize and unwilling to make it any easier"), and Stephen King ("The man is a ferociously talented writer"), Ellison's career has been marked by disputation, controversy, and braggadocio. He can be frustrating, off-putting. But he is also inspiring.

Neil Gaiman is not the only reader to have grown up on Ellison. Another is Jason Davis, who since 2010 has edited 16 collections of the master's work for HarlanEllisonBooks.com. A few weeks ago, Davis launched "The Harlan Ellison Books Preservation Project" on the crowd-funding site Kickstarter.com. The goal, Davis writes, is "to create definitive, digital versions from the preferred text of all Harlan Ellison's writings, both fiction and nonfiction," culled from the 26 four-foot-wide drawers of manuscripts in Ellison's home, the so-called Lost Aztec Temple of Mars. If Davis meets his goal of $100,000 by noon on December 1, there will be 35 revised editions of Ellison's major collections of stories and essays, as well as five new collections, available online. As I write, he has raised some $79,436.

I chipped in because I happen to be one of those kids who never quite recovered from his first reading of Harlan Ellison. They say the golden age of science fiction is 12 years old, which is around the time I became aware of this garrulous, combustible, fearless, irascible spinner of tales. It happened something like this: An elementary-school Trekker, I consumed the tie-in novels published by Pocket Books, especially the titles written by comics scribe Peter David. Browsing in Crown or Walden Books one day, I came across the twenty-fifth anniversary edition of Ellison's teleplay for "City on the Edge of Forever," which included an afterword by David. Having convinced my mom or grandmother to buy it, I returned home, read David's contribution first, then turned to the beginning to read Ellison's introductory essay describing his struggles with Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry. Twenty-five caustic and funny and discursive pages later, I was hooked.

What enraptures the reader, especially the adolescent one, is the very force of Ellison's personality: mischievous, erudite, emphatic, poetic, committed. The words cross the page at terminal velocity as Ellison involves you in the daily life of a writer in Hollywood: pitch meetings, contract disputes, story conferences, the thousand interactions with the petty and unimaginative and bourgeois that give Ellison and his young audience a sense of moral and intellectual superiority. In his prefaces, introductions, and comments, as well as in the stories themselves, Ellison is determined to convince the reader that the act of writing matters, that the profession of writer is a noble one, and that imagination and dedication and ethical behavior still count. Not only does his work contain vivid characters—Harlequin, Ticktockman, Deathbird, Vic and Blood, Maggie—it is also the production of a character: Ellison himself.

"It could be argued that Harlan Ellison possesses the romantic imagination without quite enough of the romantic discipline," wrote Michael Moorcock in his foreword to The Fantasies of Harlan Ellison (1979). "Instead he substitutes performance: Keep it fast, keep it funny, keep 'em fazed." The books are not prosaic. They are events, shows. "His stories are usually buried in their own weight of introductions, prefaces, running commentaries because each collection is a set (in the musical sense)," Moorcock continues. "This nonfiction is the patter designed to link material for the main numbers. Each story is an act—a performance—and almost has to be judged as a theatrical or musical improvisation around a theme." There is the work, and then there is the commentary on the work, and the more Ellison you read, the more the distinction between the fiction and the nonfiction is blurred, leaving you only with the visceral and unforgettable experience of the author himself.

About that author: He was born on May 27, 1934, in Cleveland, and raised in Painesville, Ohio. His was an unpleasant youth. He was bullied for being small, harassed for being Jewish. He ran away. He took odd jobs. His father died when he was a teenager. When he was 16 years old he became a science fiction enthusiast, edited a fanzine, attended the early conventions. He matriculated at Ohio State University in 1954 and dropped out a year later after a professor told him he couldn't write. He moved to New York City, where he lived in an apartment below another science fiction legend, Robert Silverberg. He sold his first story in 1956, was drafted the following year, left the Army in 1959, and moved to Los Angles in 1961 where he has lived since. He has been married five times. Let him finish: "He wears glasses, is left handed, has silver-grey hair and blue eyes, and would best be qualified as an opinionated extrovert, although he prefers the term 'a pain in the ass.'"

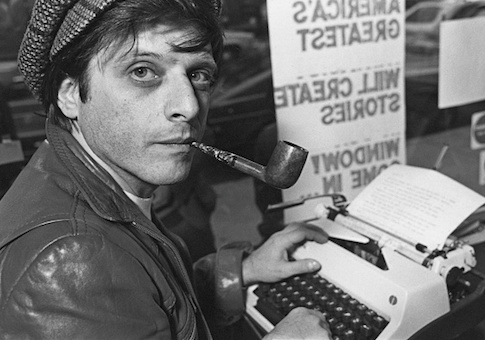

Ironic that for a teetotaler who has never used drugs and gave up smoking a pipe in the 1990s after heart surgery, Ellison established his reputation during the countercultural sixties. He was awarded the Hugo for Best Short Story three years in a row, from 1966 to 1968, the Hugo for Best Dramatic Presentation in 1967, and a special Hugo in 1968 for editing the anthology Dangerous Visions. It was Dangerous Visions that established him as both the arbiter and leading practitioner of "New Wave" or experimental science fiction. Psychedelic, multifaceted, non-chronological, allegoric, reflexive, and speckled with neologisms, intentionally garbled syntax, and references to high and popular culture, the Ellison style in The Beast That Shouted Love At the Heart of the World (1969) was at once confessional and socially aware, combining searing honesty with a left-liberal take on polarizing moral questions.

The spirit of rebellion that characterized the sixties had been present in Ellison's work for a while. "At the center of the typical Ellison tale is an elemental confrontation between man and the forces that animate his universe," writes George Edgar Slusser in Science Fiction Writers: Critical Studies of Major Authors from the Early Nineteenth Century to the Present Day. "This encounter is invariably violent, and man's condition seems to involve the survival of the fittest in a world that is not only indifferent but hostile to his existence."

Or as Ellison put it in his introduction to Beast: "Man is building for himself a darkness of world that is turning him mad; that the pressures are too great, the machines too often break down, and the alien alone cannot make it." Ellison in the sixties conceived of himself not only as a writer but also as a teacher, and he exhorted his acolytes to reform their behavior, to take direct action. "We must think new thoughts, we must love as we have never even suspected we can love, and if there is honor to violence we must get it on at once, have done with it, try to live with our guilt for having so done, and move on."

You can see how this philosophy would appeal to teenagers. Read today, long after the Great Disruption, Ellison's politics seem rather immature. The call to rebellion, the life of struggle against impersonal adversarial forces, the love of nonconformity for its own sake—these themes seem utopian and stale and cliché to the contemporary reader who has to pay a mortgage, work 9 to 5, and raise children.

What remains invigorating and alive is the Ellison style. "His best stories are scarcely stories at all," wrote Moorcock. "They are images, emotions, characters, collages." I have lost count of how many times I have read "'Repent, Harlequin!' Said the Ticktockman," "Grail," "All the Sounds of Fear," "Jeffty Is Five," "All the Lies That Are My Life," "The Man Who Rowed Christopher Columbus Ashore," "On the Downhill Side," "Pretty Maggie Moneyeyes," "Shatterday," "The Hour That Stretches," "Paladin of the Lost Hour," "I'm Looking for Kadak," "How's the Nightlife on Cissalda," "From A to Z in the Chocolate Alphabet," above all "The Deathbird," and the introductions, interstitial material, essays, columns, reviews, asides, and commentary. Like the title character in "Jeffty Is Five," these works never grow old.

The star of the long-running Harlan Ellison show is 82 now. A stroke two years ago slowed him down somewhat, though not nearly enough to stop him from working. What his admirers fear above all is the loss of his voice—sometimes annoying, sometimes sappy, always funny, always insistent, and always arresting. As George Edgar Slusser puts it, "In its ubiquity and insistence, this voice becomes both guardian and guarantor of the stories, projecting a sense that here is not dead but living discourse—words spoken and re-spoken that are worthy of being guided through the years, mediated to other human beings, and reassessed in terms of their relevance again and again."

It is this voice—Harlan Ellison's voice—that deserves preservation for generations of readers, of writers, of 12 year olds who dream of other worlds.